Exploring a century on the water from learners to fanatics.

Since the foundation of Eton College, it’s close proximity to the River Thames has shaped the school’s relationship to both sport and leisure, and boys have utilised the Thames for a variety of activities including rowing and swimming. Historically, Eton boys had several favourite bathing spots scattered around the Thames region near Eton including Cuckoo Weir just beyond the Brocas, Boveney Lock in Maidenhead, and Athens opposite what is now the Royal Windsor Racecourse. Recently, the College constructed a state-of-the-art swimming pool named Athens after the most famous of these spots, demonstrating the College’s commitment to water accessibility for Etonians, members of partner schools, and the local communities of Slough and Windsor.

Currently on display in College Library are several objects showcasing Eton College’s relationship with the Thames and the wider culture of swimming throughout the 19th century, and some highlights are showcased here in this blog post. (Clicking on an image opens it in full-size in a new tab.)

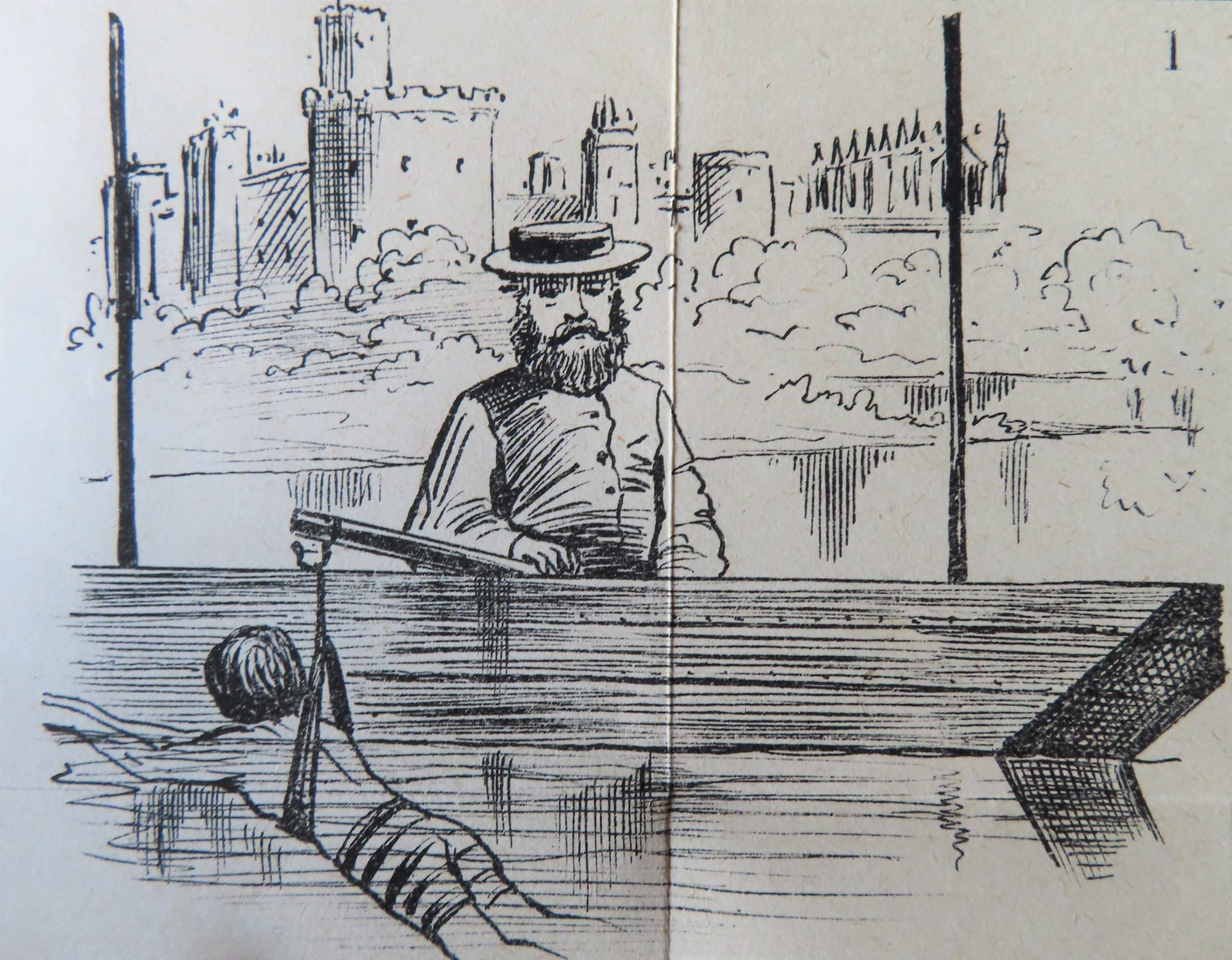

Photograph of Joe Underwood, College Waterman, 1890s [PA-DP.7:10-2017]

Watermen were employed to invigilate the various bathing spots frequented by Etonians on the River Thames. As their responsibilities were varied and demanding, it was compulsory for them to be strong swimmers and divers. Rather sombrely, watermen were provided with a list of instructions to follow in the unfortunate event of a boy drowning. With the introduction of water safety measures from 1840 onward, fewer boys became victims of the Thames.

We have a surprising number of photographs of Watermen in the College’s Photographic Archive, with several of their names recorded. Comparatively, we have very few images of other support staff, which might suggest that Watermen were particularly well-respected members of the Eton community. Additionally, several of these photographs were taken while the Watermen were in-situ on the job, providing a visual insight into the material culture associated with their role, including their clothing and boating equipment.

Fig. 1: A Waterman teaches a boy to swim. Illustration from J. C. Leahy, The Art of Swimming in the Eton Style, London, 1875 [below].

From the mid-nineteenth century onwards, water examinations became mandatory before a boy was permitted to bath or bathe. In the archive, we have the River Masters passing books that list the dates and names of boys who passed their examination, which took place at the beginning of the Summer half. (SCH SP SW 01). Boys who hadn’t passed their tests were known as ‘non-nants’, nant being a Latin derivative for ‘swim’. Once passed, boys would simply be known as nants, and a list would be put up in each house of the boys who had not passed their test. Naturally out of pride, every house competed to have the fewest number of non-nants on their lists.

J. C. Leahy, The Art of Swimming in the Eton Style, London, 1875 [ECL Ib4.2.07]

This illustrated hand-book, written by one of Eton’s former swimming masters, provides instructions on general water safety and methods of swimming. The particular ‘Eton Style’ involved kicking out with the flat soles of the feet and emphasised the importance of floating in an emergency. Somewhat progressively for the late nineteenth-century, Leahy recommends that women should be taught how to swim, both for safety and general exercise—and even argued that some of his female students swam better than the Eton boys!

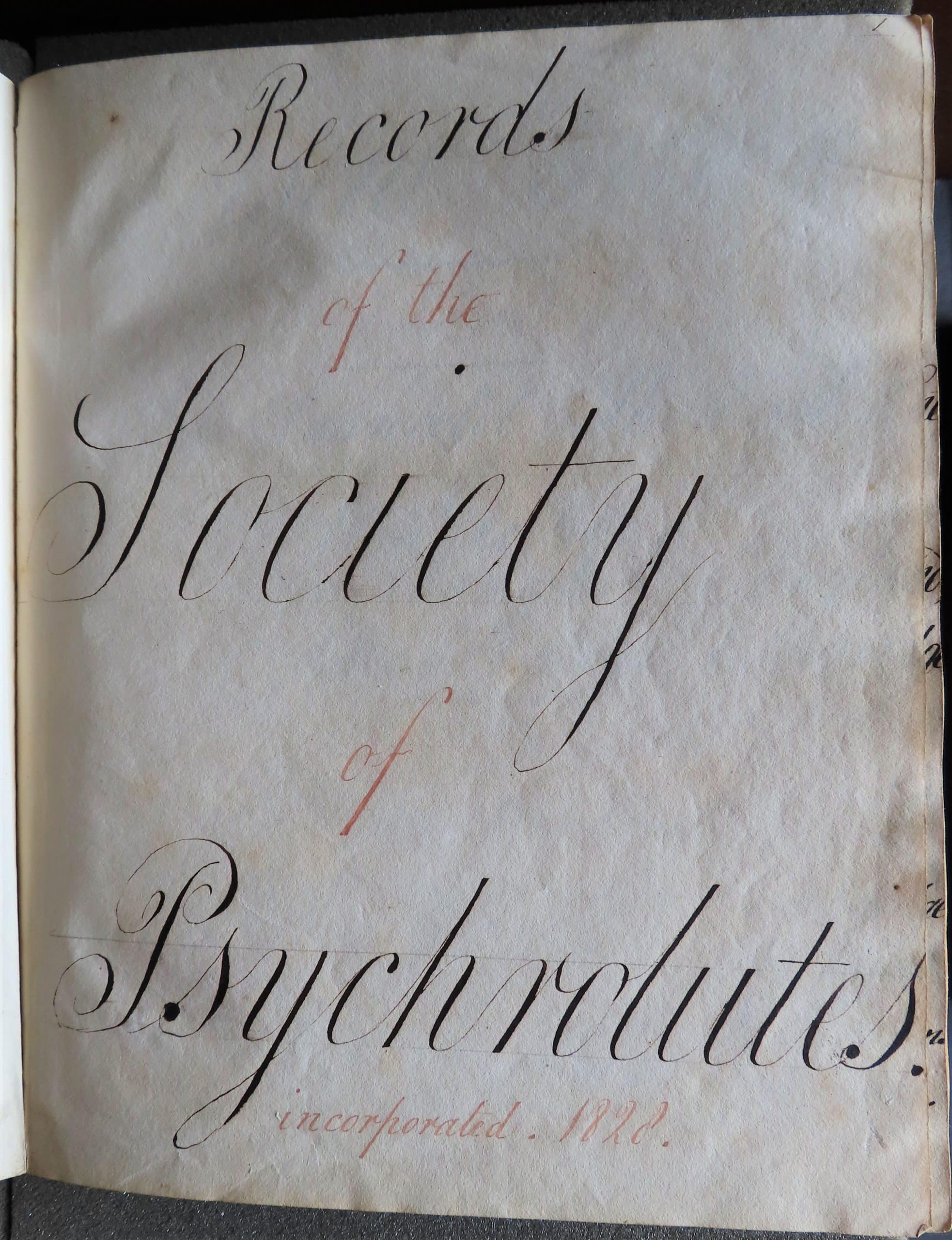

Book of the Society of Psychrolutes, 1828-1857 [MISC PSY 01 01]

The word ‘psychrolute’ comes from the Ancient Greek for ‘cold’ (ψῡχρός) and ‘wash’ (λούω) and refers to cold-water bathing. The Society of Psychrolutes was founded in 1828, possibly at Cambridge University, with members also coming from Eton and Oxford. Qualification for membership was a dedication to bathing out of doors between November and March. In 1833 it appears that the Society’s remaining funds were handed to the ‘Eton Royal Philolutic Society’, established in 1832 at Eton for the lovers of bathing in general rather than winter bathing, and its leading lights were William Evans and George Selwyn, later Bishop of New Zealand.

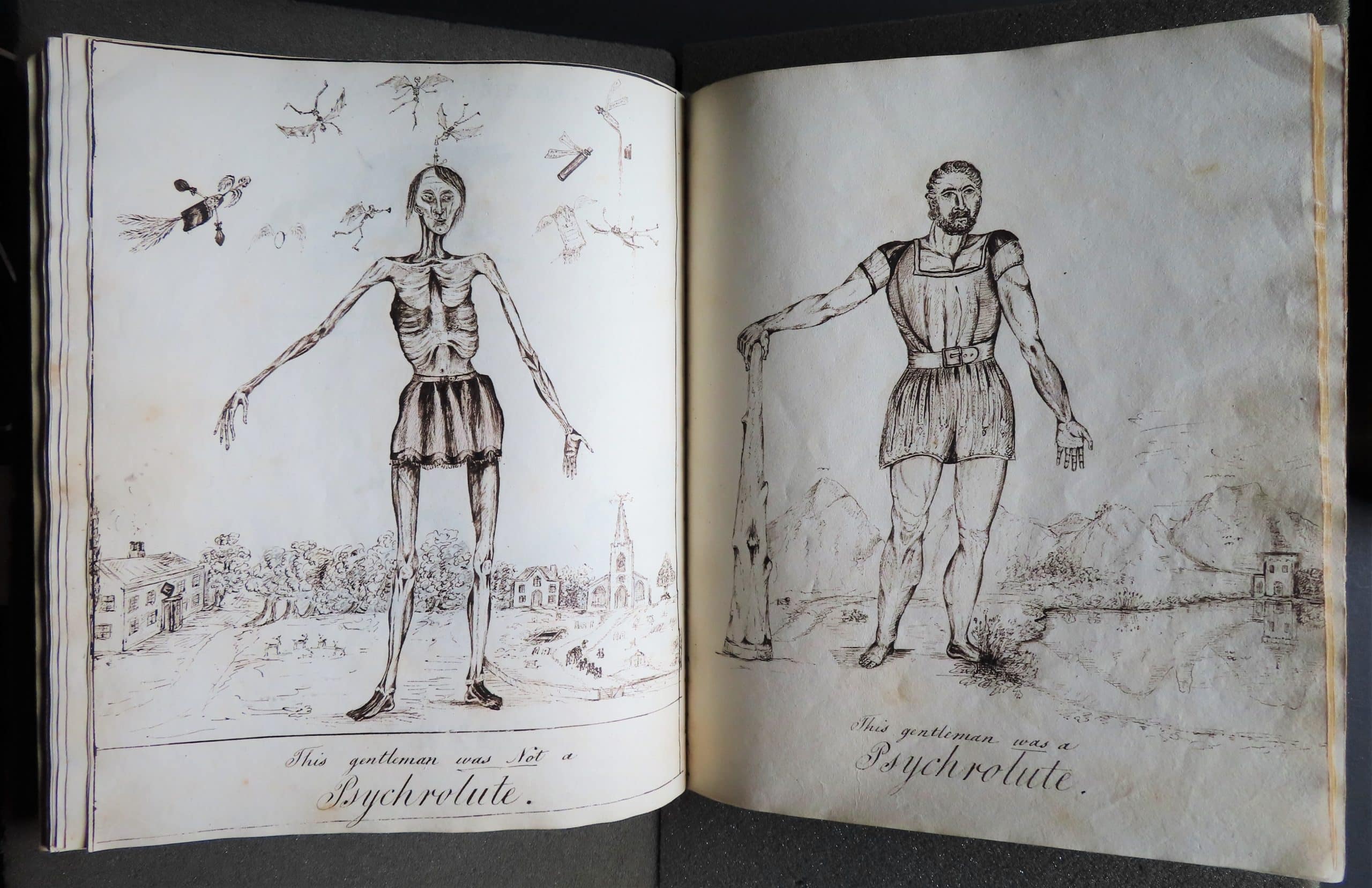

The opening currently on display from the Book of Psychrolutes (shown below) depicts two men, one skeletal and one muscular. These images reinforce traditional ideas of masculinity: Psychrolutic men demonstrated their mental and physical prowess by bathing during the winter months. At the same time, these caricatures are tongue-in-cheek, drawing on the timeless appeal of ‘us-and-them’ rhetoric. It is interesting to note an English village scene in the background of the non-Psychrolute, contrasted with the idealised, perhaps classical or mythic, background enjoyed by his cold-water companion. There is much more to see in this remarkably detailed drawing—click below to open it, and let us know your thoughts on Twitter!

By Alexander Taylor, Archives Assistant.