Preserving the Victorian technology that captured a bygone Eton.

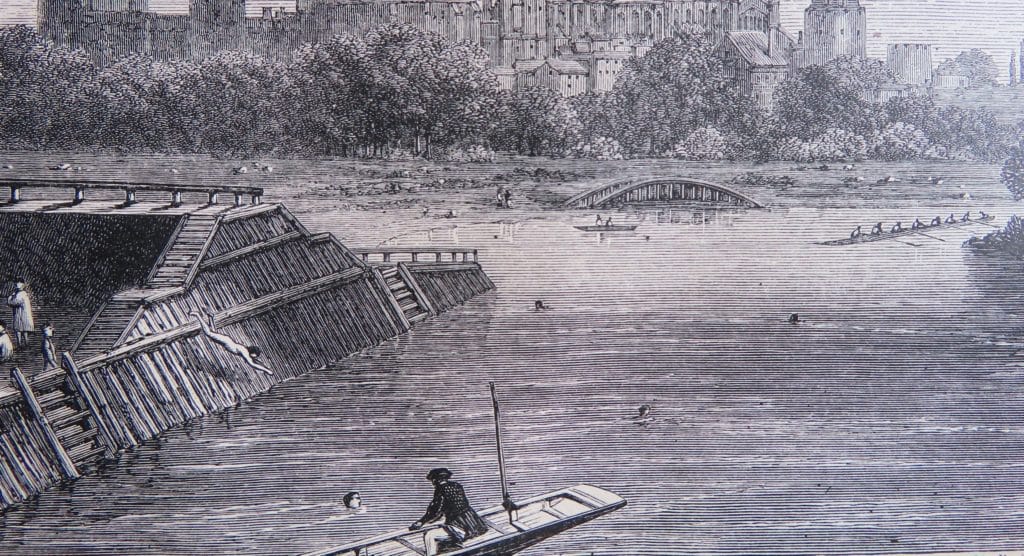

If you’ve ever admired a photograph from the late 19th or early 20th centuries, chances are it was captured by utilising a glass plate negative. These days the word “negative” in the photographic sense conjures up images of those thin, brown plastic strips that came tucked into envelopes with our freshly developed prints — but in the 1850s it referred to a much more fascinating method of producing photographs that had been invented by the British sculptor Frederick Scott Archer (1813-1857). This method involved coating sheets of glass on one side with a collodion mix of cellulose nitrate and ether. The glass sheet was then dipped into a bath of silver nitrate and quickly inserted into the camera stand in order to expose the plate before it dried. These “wet plate” negatives often had uneven coatings of emulsion layered on to thick sheets of glass with rough edges. Sometimes they even included a thumbprint where the photographer had held the plate while applying the emulsion!

ABOVE: Example of “wet plate” photography featuring thumbprint and streaking on lower right-hand corner and along bottom edge, 1863 [PA-B.200_15-2016]. Click on an image in this blog to open it full-size in a new tab.

As one can imagine this wet process was somewhat messy and time sensitive so it was fortuitous that, in 1871, Dr Richard L. Maddox (1816-1902) created a “dry plate” negative which used thinner sheets of glass coated much more evenly with an emulsion of gelatine and silver nitrate. These plates were then left to dry and became much more stable and transportable as they could be stored and used to capture images when needed. They also required less exposure to light — and as such became the gateway to commercially viable photography.

ABOVE: Before processing, glass plate negatives have an ‘inverted’ appearance [PA-B.uncat.]

Whilst the invention of glass plate negatives as a medium was a revolutionary development, the plates themselves do present very specific preservation challenges. The emulsion used to coat the glass was often a proprietary mix which varied widely from photographer to photographer, meaning that the chemical composition of each plate is quite different (even those from the same photographer). The glass sheet is also prone to breakage and the emulsion layer vulnerable to flaking and scratching. Additionally, recent research has discovered that the glass itself can suffer chemical degradation and this makes for a tricky medium to keep stable. As a rule, glass plate negatives require cool (but not cold) temperatures and a low relative humidity to slow the reactions that lead to degradation.

ABOVE: Despite damage including extensive flaking, the main image remains remarkably clear, in this late example of plate photography,1905 [PA-B.212.14-2016]

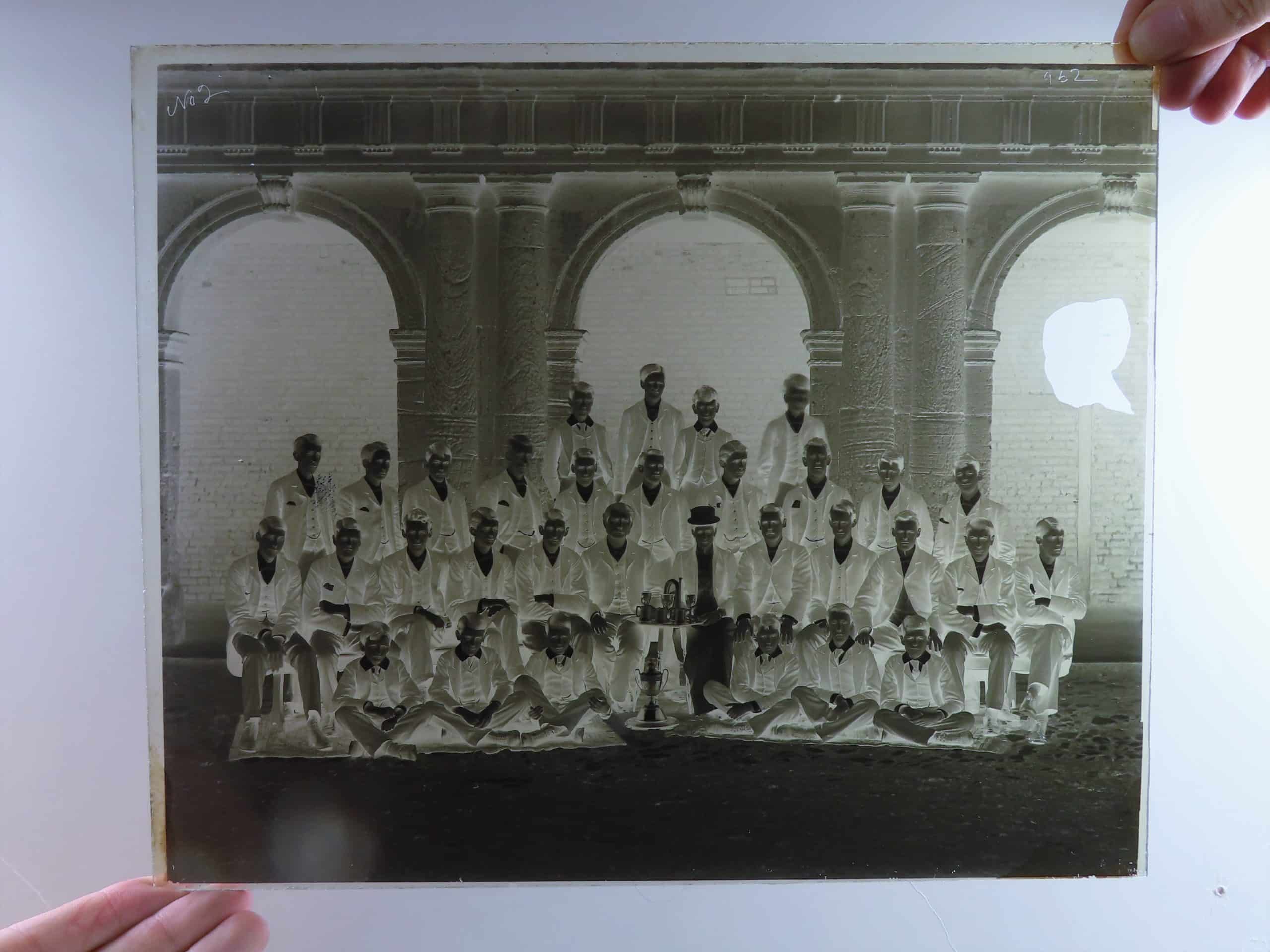

Within Eton College’s Photographic Archive, there are some wonderful examples of over 3000 glass plate negatives and the beautifully detailed prints they produce. Some of our earliest images in the collections date from the 1860s and these would have undoubtedly been created using glass plate negatives. They encompass a range of subjects from House Groups and sporting groups to Speeches and the Eton Society. We have recently acquired a large deposit of glass plate negatives that were rescued some years ago having been destined for the skip! Before they came to us they had been stored in a garage and as such require a lot of cleaning and care before processing into digital-format images, but when this work has been completed we are excited to add more unique images to our growing photographic collections.

ABOVE: In the first floor window, two children struggle to keep still for the camera despite the maids’ efforts, 1890s [PA-B.202_21-2016, PA-B.202_25-2016]

Glass plate negatives, though fragile and requiring careful storage conditions, were an innovative leap forward in the photography timeline. The crisp images they produced sometimes rival even the digital prints of modern-day. In fact, quite often a glass plate negative which appears cracked or badly damaged on the emulsion side can still produce a clear and detailed print over a hundred years later!

By Mishka Chisholm, Assistant Archivist

Further resources

To date, we have digitised nearly 200 glass plate negative photographs. These can be viewed by searching for the keyword ‘glass plate’ on our Online Catalogue.

To learn more about the glass negative process, we recommend this video from the Royal Collections Trust: