Collections Home What’s On Events College Chapel

College Chapel

College Chapel

Collections Home What’s On Events College Chapel

College Chapel

This architectural trail begins with the building which was started at the earliest date, Eton College Chapel. Begin in the churchyard, just off Eton High Street, looking up at the south façade of the Perpendicular Gothic building, with its pinnacled buttresses and traceried windows. Henry VI wanted to commission a chapel that he hoped would become one of the greatest pilgrimage churches in Europe. The foundation stone was laid in 1441.

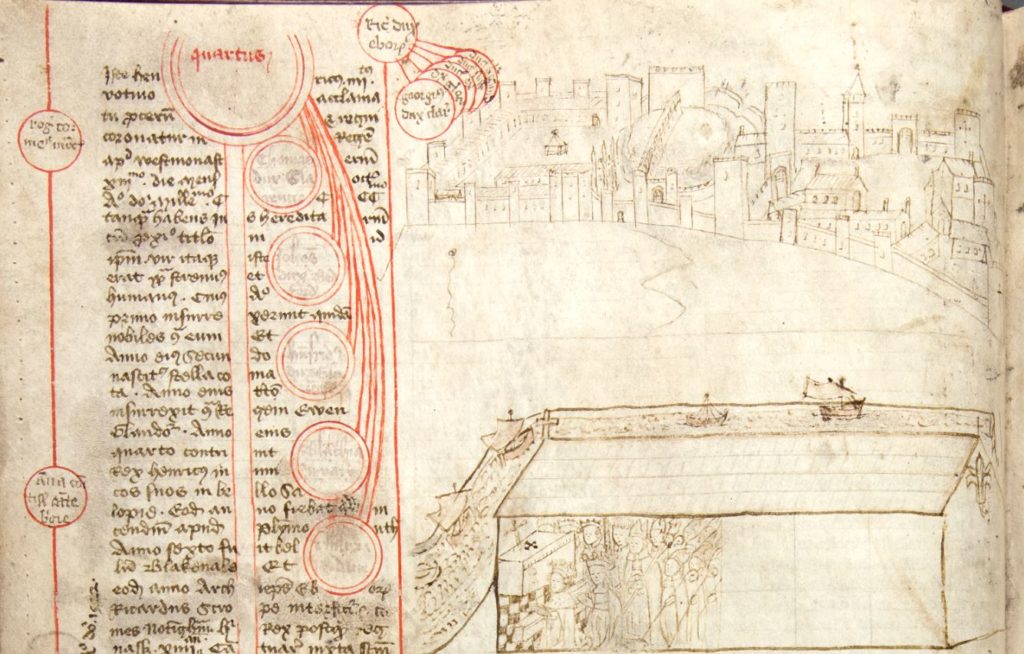

The building was dedicated to the Virgin Mary, to whom the college is also dedicated. For the next eight years, construction continued on the building and the first mass was celebrated at an altar within the unfinished chapel in 1443. You can see a representation of Henry VI and his wife, Margaret of Anjou celebrating mass at the altar of Eton College Chapel in the illustration below, from Ranulf Higden’s Polychronicon, written in the 15th century.

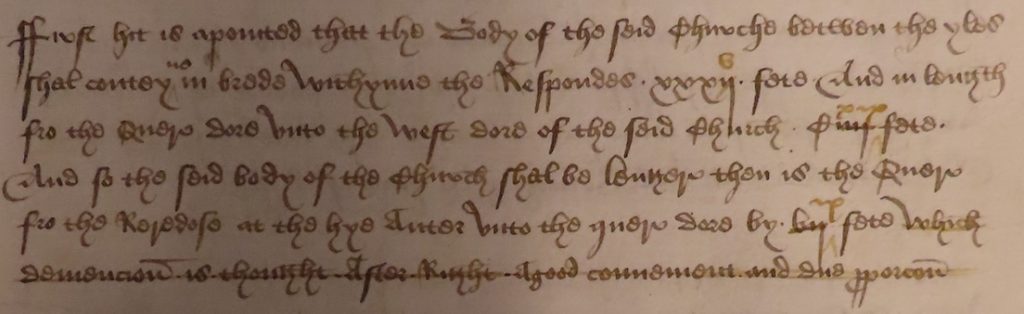

However, on 7 February 1448, King Henry ordered the masons to re-start the building of the chapel from its foundations. Shockingly, the results of seven years of work were destroyed in their entirety. The newly appointed Master of Works, Roger Keyes from All Soul’s College, Oxford, was dispatched to measure both Salisbury and Winchester Cathedrals, and it was concluded that Eton College Chapel should be re-built 47ft longer, 8ft broader and 20ft higher. The structure that you see today was the result of new management, new stone and new, much grander plans, executed after 1448.

The reasons for Henry’s sudden change of heart have remained a mystery for centuries, and a variety of theories have been suggested as to how he came to this seemingly radical decision. Some maintain that the decision to start again was to impress his wife, Margaret D’Anjou whom he had married in 1445, and others argue it was a result of his poor mental health. The most probable explanation, put forward by historian K. Selway in 1993, has been strengthened by previously unexamined geological evidence and research carried out by Phil Macleod, a current teacher at Eton.

Selway suggests that a structural defect is likely to be the main reason for the upheaval – in fact it is recorded that the chancel was undermined by flood water from the Thames at one point. In 1448, the churchyard itself was raised by 4ft and then the chancel floor was built 10ft above that. The King also forbade the use of water-prone brick, chalk and Reigate stone. In the second version of the chapel, Taynton stone was used for the first course, and a combination of Taynton and Dolomite in the second, replacing the less durable Caen and Kentish Rag. Overall, this is estimated to have cost the King 54% more per tonne. Both Taynton and Dolomite had been used at Windsor Castle, and Taynton at All Souls, Oxford, so they were both proven to be durable building stones.

In his 1447 plan, Henry envisaged a cathedralesque church with side aisles and a nave which was to be twice the length of the present chapel. However, after he was deposed in 1461, work was halted and the proposed chapel plan was never completed in its entirety. A plaque on Keate’s Lane, indicated on the trail map, marks the grand proposed length of Henry VI’s chapel. However, Henry’s order that the chapel be ‘edified of the most substantial and best abiding stuff of stone’ was certainly followed. If you would like to read more about King Henry’s plans to create a pilgrimage chapel, do delve into the blog post Henry VI: From Progress to Pilgrimage.

As you pass by, make sure you look up to the external, west wall of the chapel, where you can see a memorial to the second Provost of Eton, William de Waynflete (1398-1446), Bishop of Winchester, who paid for the completion of College Chapel – which included the addition of the Antechapel, instead of the great nave that Henry VI had planned, between 1476-83.