Collections Home What’s On Events Taynton and Dolomite

Building Materials

Collections Home What’s On Events Taynton and Dolomite

Why are Taynton and Dolomite such durable building materials?

Taynton

This Jurassic era limestone was formed 175 million years ago and was dug from quarries in Taynton, Oxfordshire. The conditions of the seas from which Taynton was formed were very much like those currently found off Florida and the warm shallow sea teamed with life. Amazingly if you look very closely at some of the blocks, you can see remnants of the shells of these creatures. In School Yard, you can even make out a fossilised Jurassic urchin in the Taynton on one of the blocks used to create the exterior staircase up to Lupton’s Chapel.

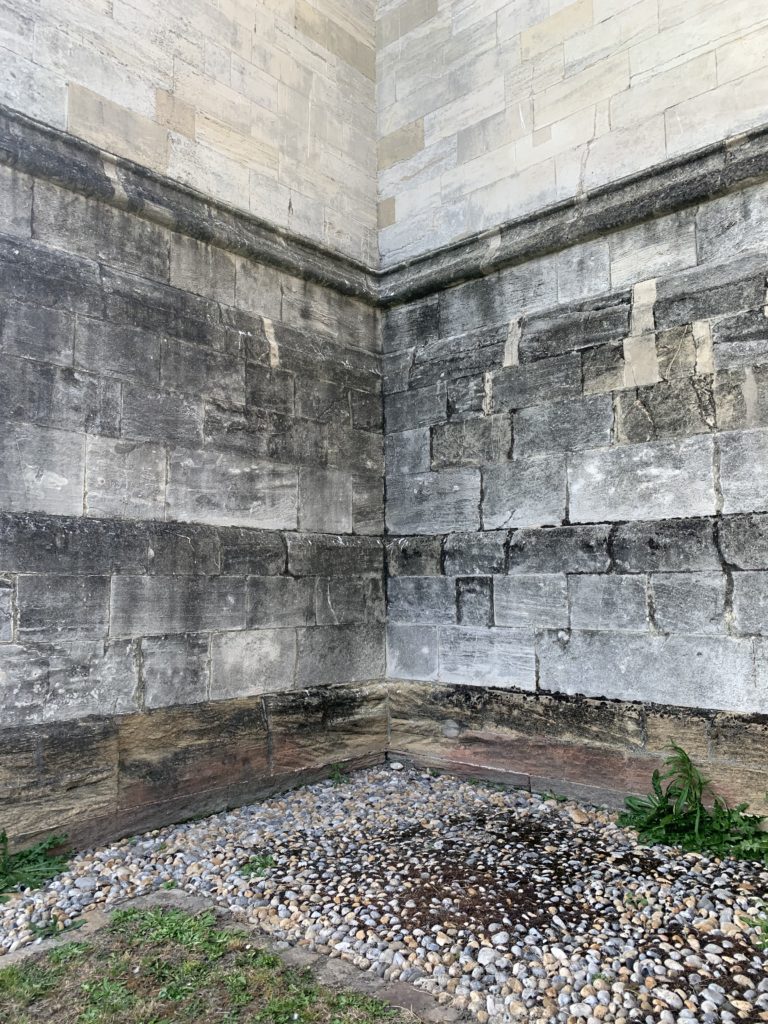

The stone is brown, largely grained and shelly and resists the destructive forces of freezing by allowing sufficient space for the expansion of water. Taynton stone was not just used in the construction of the lower stages of buttresses but utilised all over the building, even for the pinnacles and crockets.

Notice the way the Taynton blocks are used. The majority are orientated so that the cross bedding is parallel to the ground and therefore its weight-bearing capacity is optimised. When looking at any stone, you can trace your fingers along the horizontal lines which indicate the way it was laid down millions of years ago. The coarse grain makes it easy to identify.

Dolomite

Dolomite stone was formed 230 million years ago in a drying intra-continental sea. Its formation was a result of lime muds of calcium carbonate being permeated by magnesium brines, which replaced much of the lime. The result is a double carbonate rock, immune to the attack of acid rain and it is also practically impervious to water. It is a very white stone and was used for external weight bearing buttresses and walls.

If you look up at the chapel from the graveyard, you should be able to identify both Taynton and Dolomite stone. Above the drip-course:

- The creamy white stone is Dolomite

- The coarse-grained, browner stone is Taynton.

- The blocks which look rather weathered and have suffered most from the ravages of time are Kentish Rag. This was used in the initial build for the chapel and re-used in the second design after 1448.

- Blocks of Kentish Rag which have been extensively damaged have been replaced over time with Clipsham stone, an oolitic limestone from Rutland. Their presence is given away by their angular, new appearance (especially on the corners) and the colour is more yellow than the grey of the Kentish Rag.

Why are there rose-coloured patches on some of the stones?

There is further geological evidence which reveals efforts to prevent the chapel from water damage, in this case from the floodwaters of the River Thames. There are 16 rose-pink patches of Taynton stone at a similar height around the base of the building, most of which are visible on the south-side of the chapel, closest to the river.

On viewing these stones in isolation, their discolouration seems mystifying, however, when viewed in tandem with the archival accounts of the time, which show the purchase of tiles, wax, pitch and resin – all ingredients for a specific type of cement used in ‘steyning’ a form of waterproof repair – these rose-coloured stones make more sense. Straw, a contemporary purchase of which was also recorded in the accounts, would have been laid against the wall and set on fire in order to drive off residual floodwater from the damaged stone before the application of the cement. This is evidence that the best efforts could not hold back the floodwater from the Thames, even after the new plans of 1448 started to come to fruition.