Economics is generally understood as ‘the branch of knowledge that deals with the production, distribution, consumption, and transfer of wealth’ [OED]. Pupils taking economics are often shown the exceptional work done by John Maynard Keynes when he was a boy at Eton, yet College Library houses many more volumes that engage with the gradual development of nation-based wealth in pre-modern western Europe.

They often tell of arrival of Europeans in America at the dawn of the sixteenth century, which sparked a race for the control and supremacy over the Atlantic and beyond. In the 1600s, the Dutch Republic and the kingdoms of England, Spain, and Portugal established their maritime presence globally, causing a shift in the perception of a nation’s wealth, and stimulating new economic theories and legal practices.

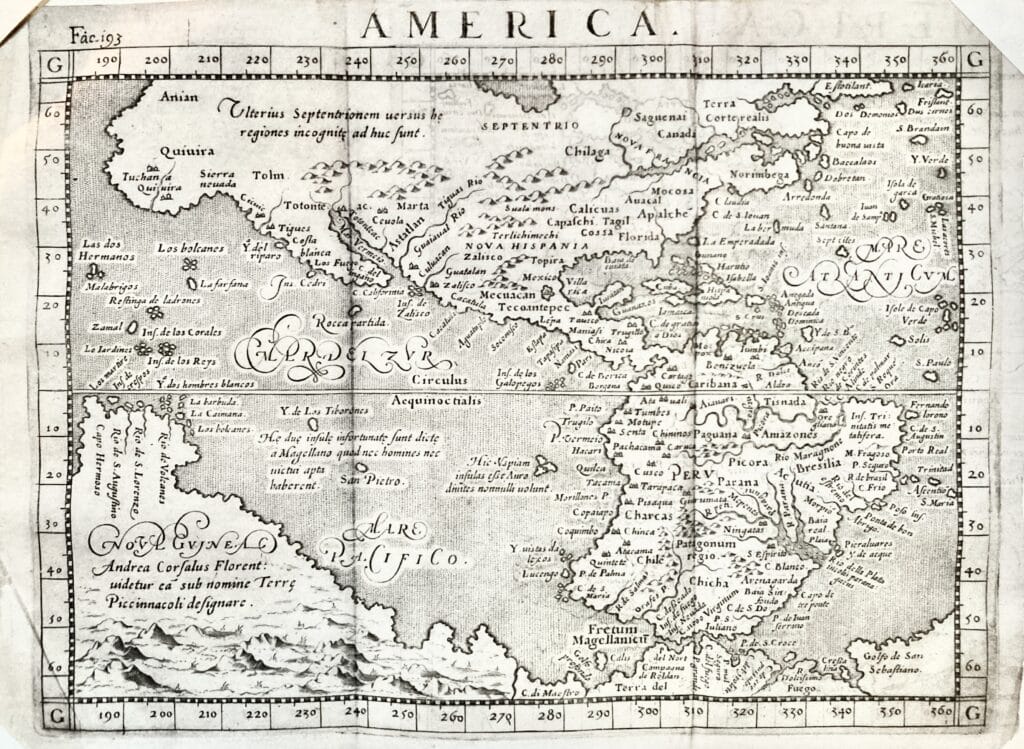

A common form of economic politics at this time was mercantilism, which argued that a nation’s wealth should be based on minimising imports and maximising exports. Giovanni Botero was one of the first Europeans to put this idea in print, producing a ‘geopolitical manual’ that brought together human geography with a systematic analysis of the physical and demographic characteristics of contemporary countries as well as their economic and military resources. The work is accompanied by maps, including an early depiction of the American continents. His ideas directly promoted colonialism in north America, which he justified as a way to “improve” the new world.

Giovanni Botero, Le relazioni universali [‘Universal relations’], Venice (1600) (ECL Gd.5.04)

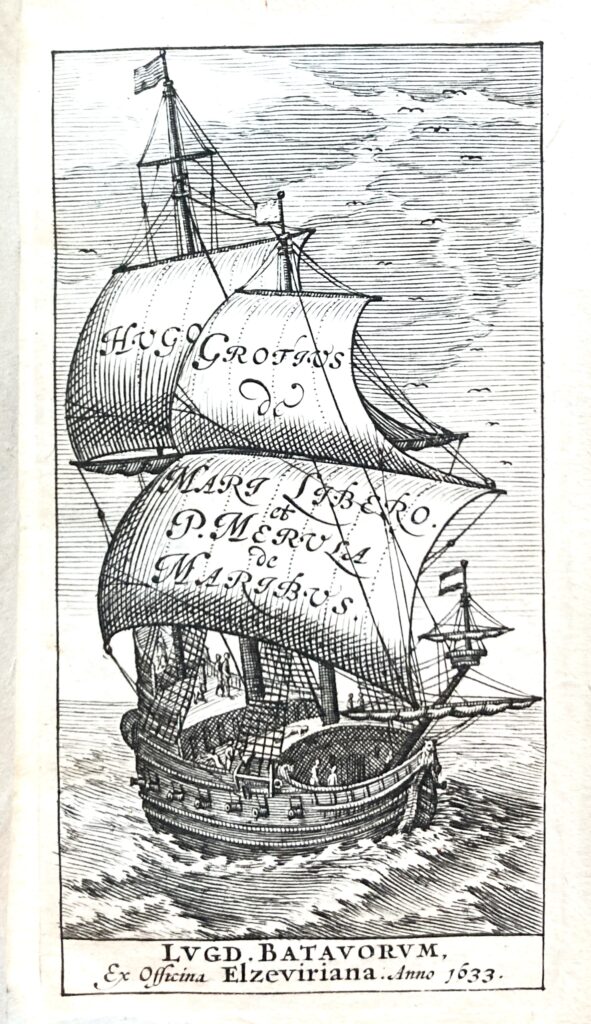

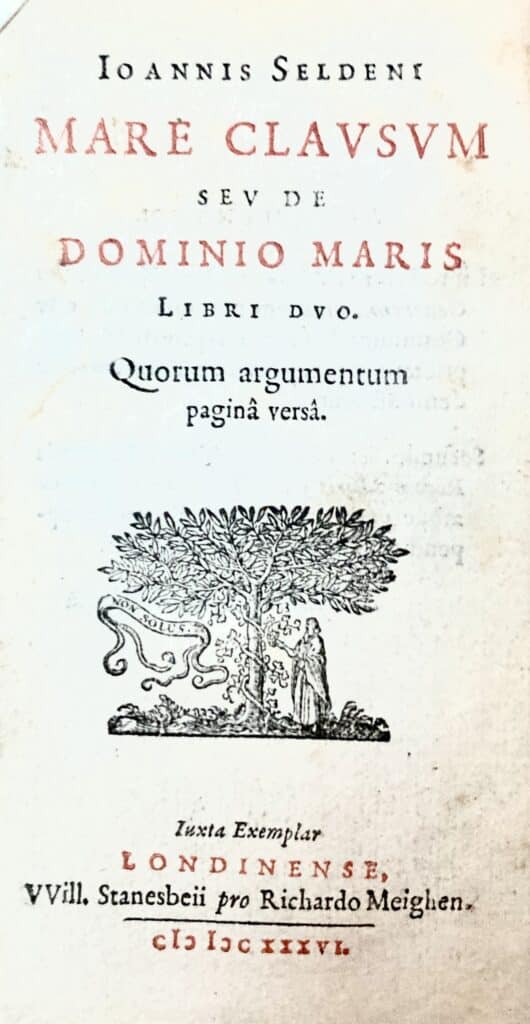

Seventeenth-century European countries also created maritime empires, which deeply affected the way nations gathered and managed wealth. As the first such empires, Spain and Portugal claimed the exclusive right to all trade beyond Europe, and argued that other Europeans were forbidden from doing so under international law. The Dutch and the English challenged these claims, establishing a tenuous presence in the Caribbean, India, and south east Asia. The Dutch position was represented by Hugo Grotius, who called this Iberian supremacy into question by arguing that the sea was common to all people and could not be alienated like land territory. The Englishman John Selden, on the other hand, favoured tighter control, declaring that England had the right to police their immediate shores. Their works De mari libero (‘On the free sea’) and Mare clausum (‘Closed sea’) outline these positions – with their titles perfectly encapsulating different interpretations of the liminality of sea space.

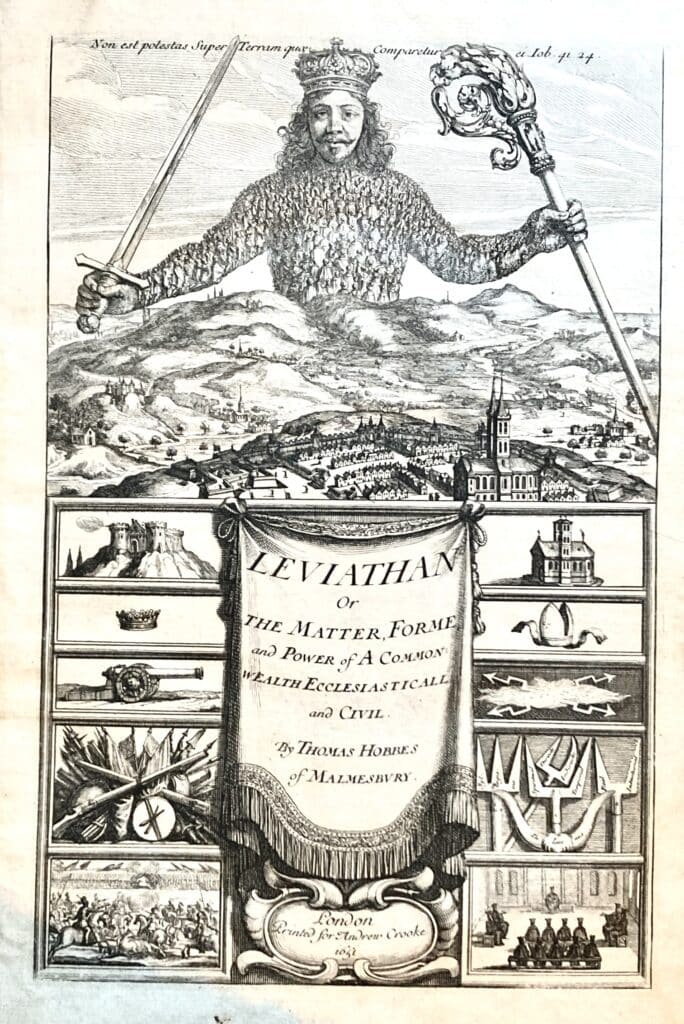

As these debates were taking place, Thomas Hobbes published his famous work, Leviathan, which likens the state to the sea serpent of the Hebrew Bible. As state regulation of overseas trade was still limited, Hobbes’ work provided important intellectual justifications for the expansion of regulatory powers in Europe. On the title page, the leviathan – an allegory for the state itself – is portrayed as being made of smaller men, symbolising the social contract between subject and ruler. The sword and sceptre he holds stand for the state’s monopoly on legitimate violence and sovereignty respectively.

Thomas Hobbes, Leviathan, or the matter, forme, & power of a common-wealth ecclesiasticall and civill. London, 1651 (ECL Gc.2.13)

These works show how trade and seafaring shaped ideas of law and state. However, the complex networks of supply and demand that informed the growth of these new empires continued to be embedded in moral and political philosophy. It would take the transition from human- to machine-based labour to distinguish a separate discipline of “economic thought” as we understand it now. These earlier works in the College Library collection help us to better understand the factors that influenced economic development over time.

Charlie Barranu