The National Garden Scheme grants visitors unique access to over 3,500 exceptional private gardens in England, Wales, Northern Ireland and the Channel Islands, including the gardens at Eton. The scheme is an opportune time to research Eton’s horticultural history through the archives. From Royal Patents granting land to facilitate the building of Eton College, to the gardens we see today, tending to the land was an important part of the school’s history.

Gardens at Eton were deemed so important, Henry VI made provisions for the creation of a garden in his will: ‘the space between the wall of the Church and the wall of the cloister shall contain 38 feet which is left for to set in certain trees and flowers, behovable and convenient for the service of the same church.’

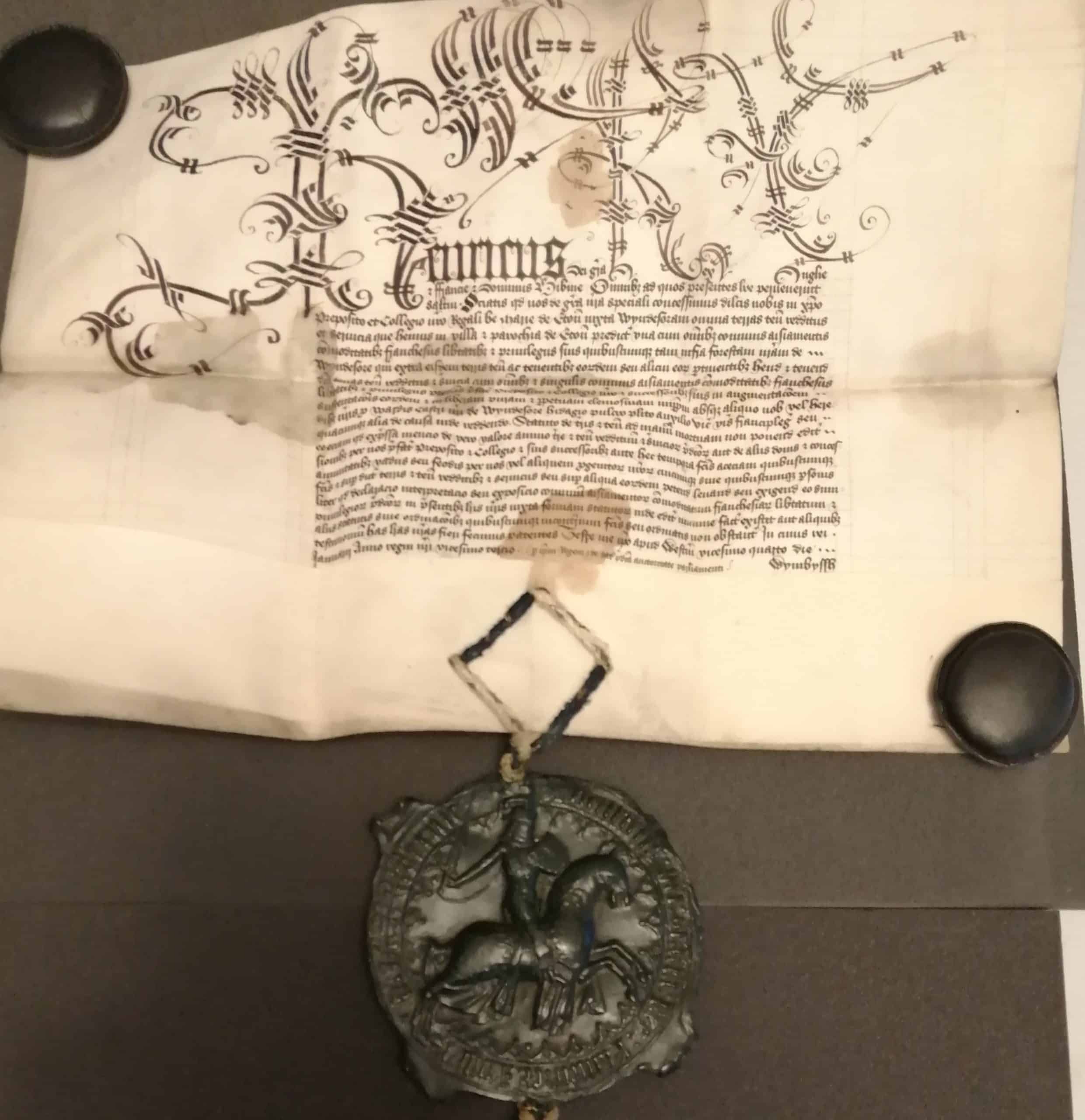

The gardens at Eton were established on land granted to the College by Henry VI. Through a succession of grants over a number of years, the King gave land to the Provost and College, purchasing all available gardens, homes, lands and fields in Eton.

The deeds housed in the College Archives show this generosity. Maxwell Lyte, in his magisterial work A History of Eton College cites Huntercombe’s Garden as one such plot of land and explains that ‘a careful antiquary might doubtless identify most of the localities by means of early deeds.’ These deeds are not only important for understanding the history of the land the gardens eventually came to be built on, they also provide an insight into the landscape history of the parish of Eton.

The audit books then provide a more detailed glimpse into the agricultural pursuits of the College. For example, in 1590, the College experimented with growing hops for their own consumption; although the hop garden was ultimately unsuccessful, the area marked out for this purpose retained its name now reflected in the boarding house, The Hopgarden. They also shed light on the plants and trees favoured by the College, for example in 1662 Eton purchased two dozen Dutch gooseberry plants, 400 raspberry plants and planted a dozen apple trees in 1663.

Grant of all the King’s lands in Eton

ECR 39/40A

Royal Patent: Grant of all the King’s lands in Eton, 24 January 1445 [ECR 39 40 A]

This is a grant of land conferring the King’s land in the town and parish of Eton to the Provost and College of Eton. It was on land granted by these royal patents from King Henry VI that the College was able to grow vegetables, graze livestock and engage in self-sustainable pursuits.

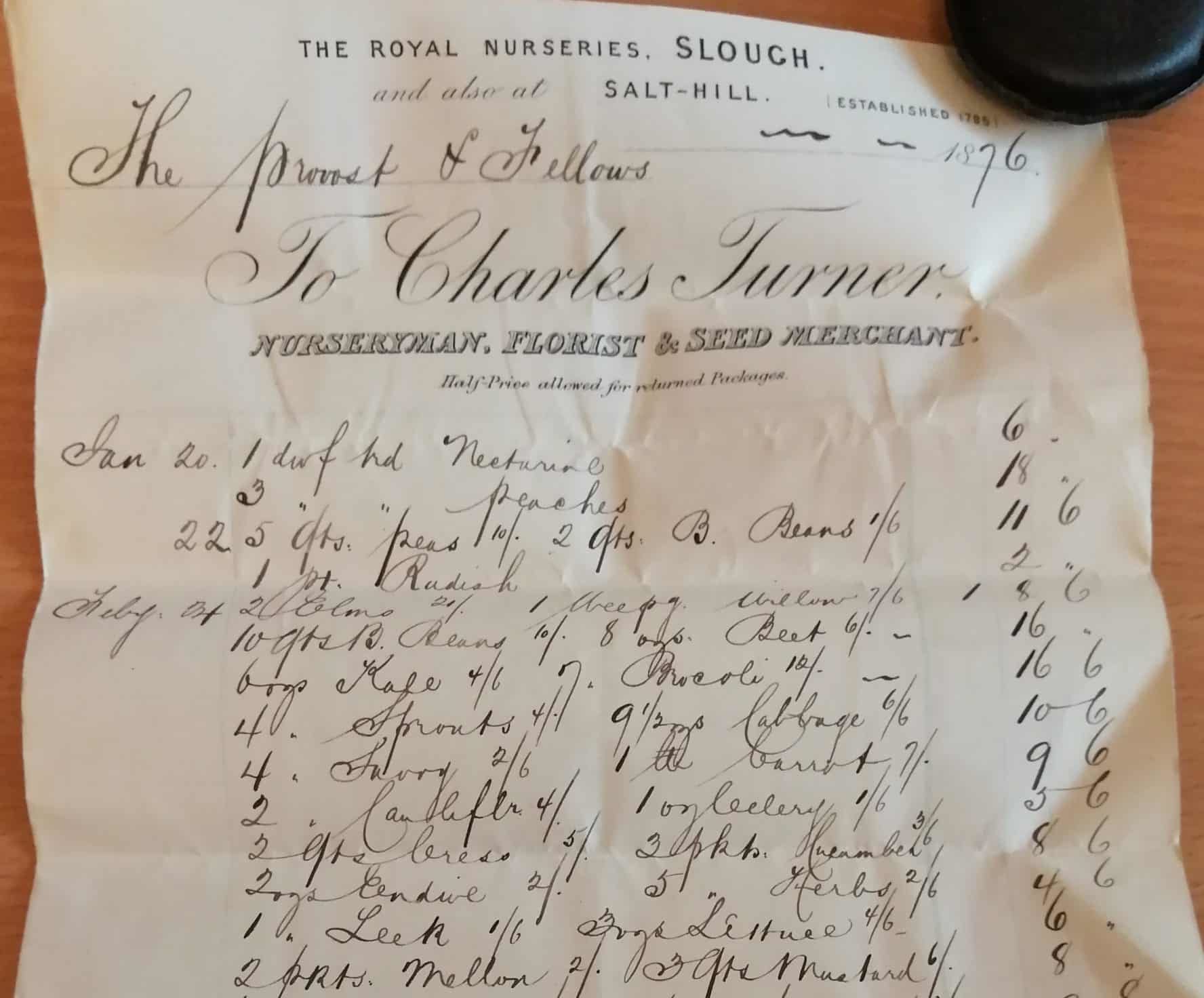

Invoice for fruit trees

COLL B 08 137/148

Invoice from Royal Nursery for fruit trees and seeds, 1876 [COLL B 08 137/148]

This invoice from 1876 the shows the purchase of a variety of trees such as nectarine, peach and elm from the Royal Nursery located in Slough. In addition to this, the invoice also lists the purchase of seeds: endive, mustard, broad beans.

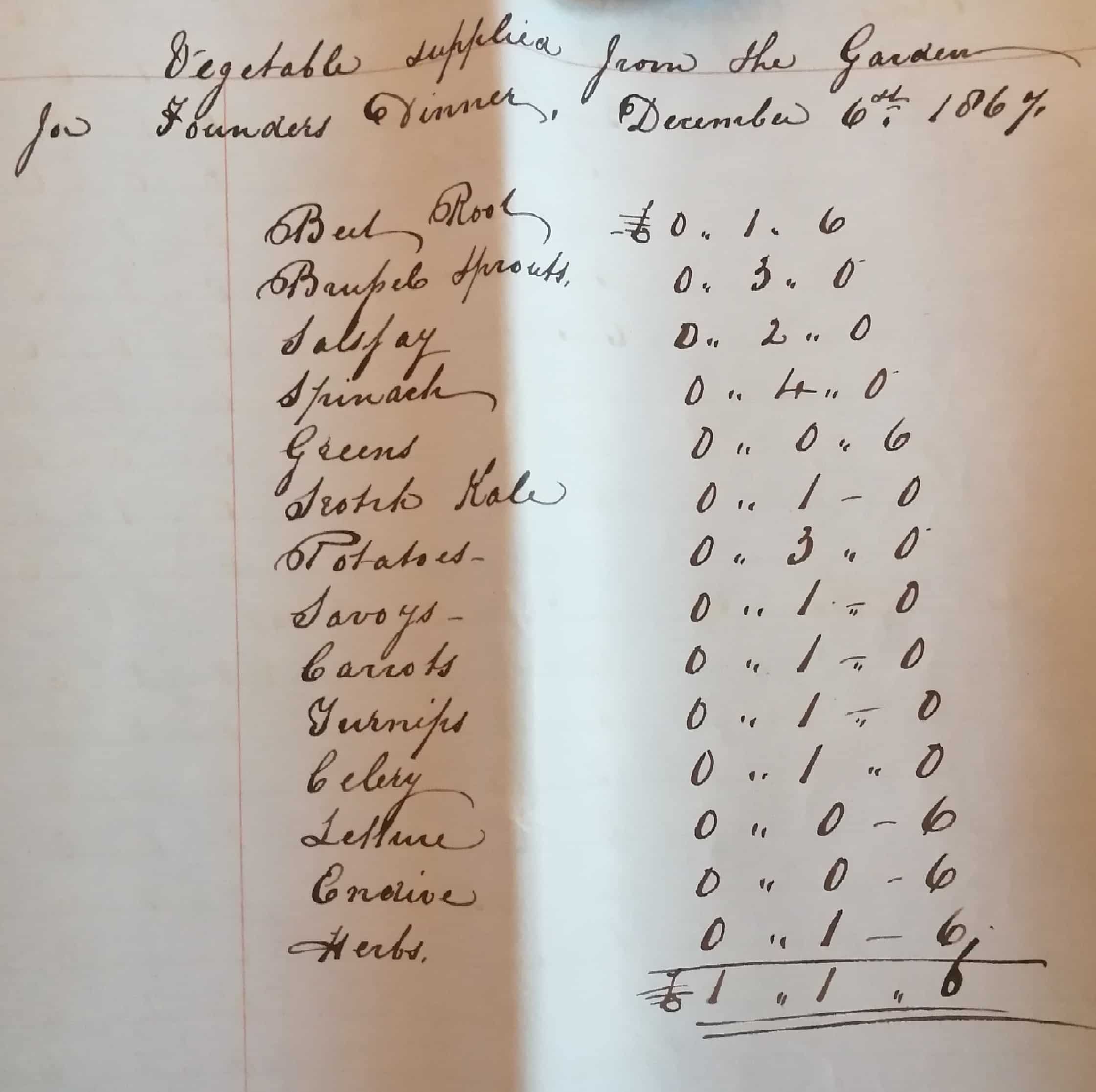

Vegetables supplied from the College gardens

COLL B 08 131/78

Vegetable List from Garden, 1868 [COLL B 08, 131/78]

This is an itemised list of the vegetables grown in the College garden and provided to College Hall for mealtimes. Some of the vegetables grown in this list include salsify, beetroot, cabbage and spinach.

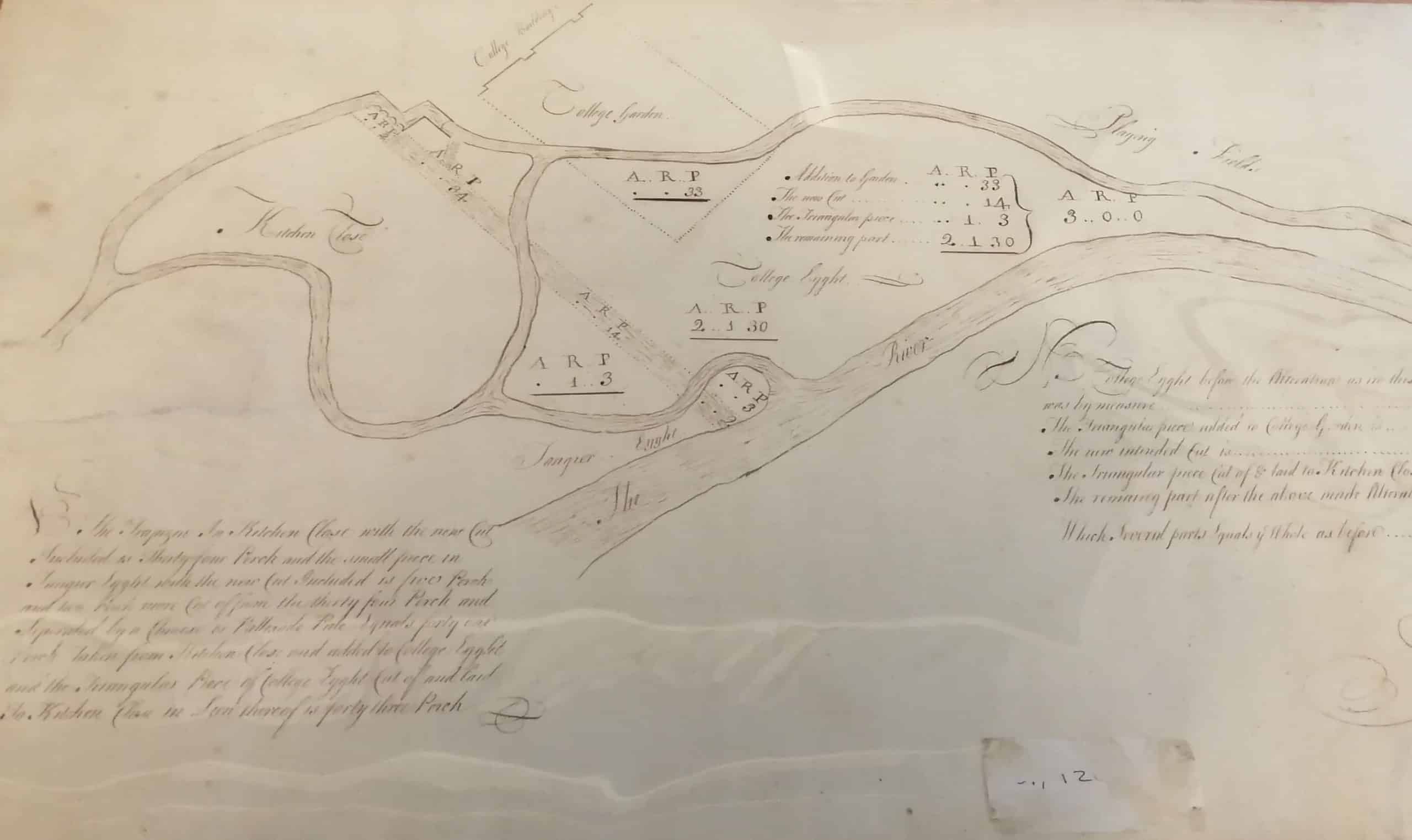

Plan of College gardens

ECR 51 124

Plan of College Eyght and Kitchen Close, mid 18th century [ECR 51/124]

The College Garden was located behind the Provost’s Lodge and a surveyance map by John Winch in the mid eighteenth century shows its location.

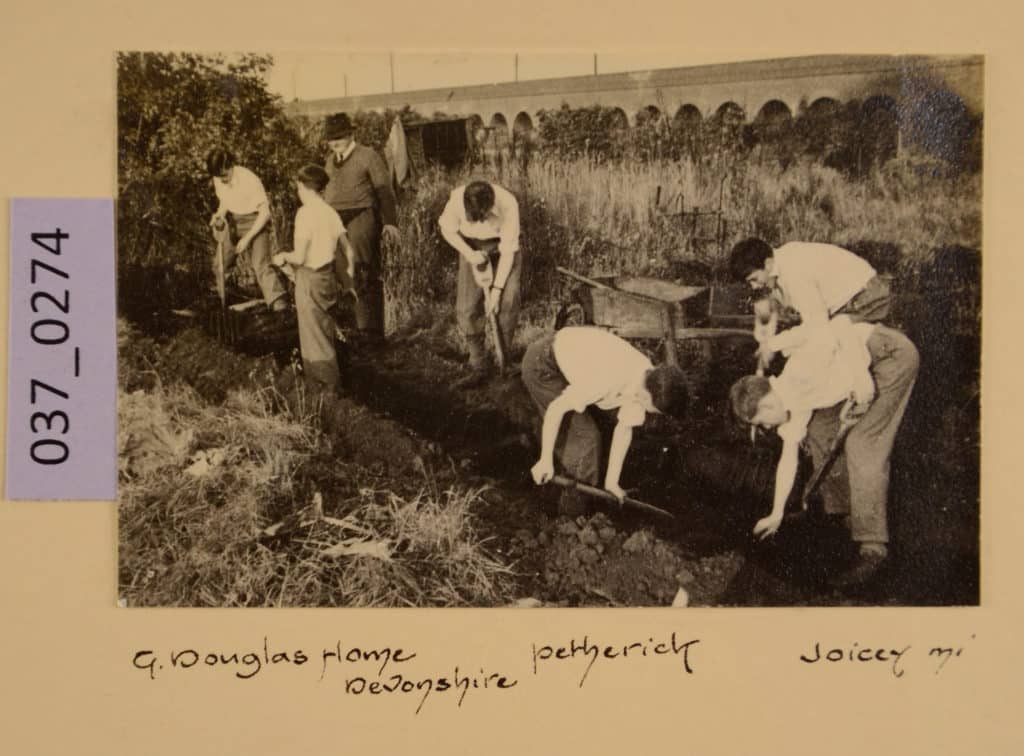

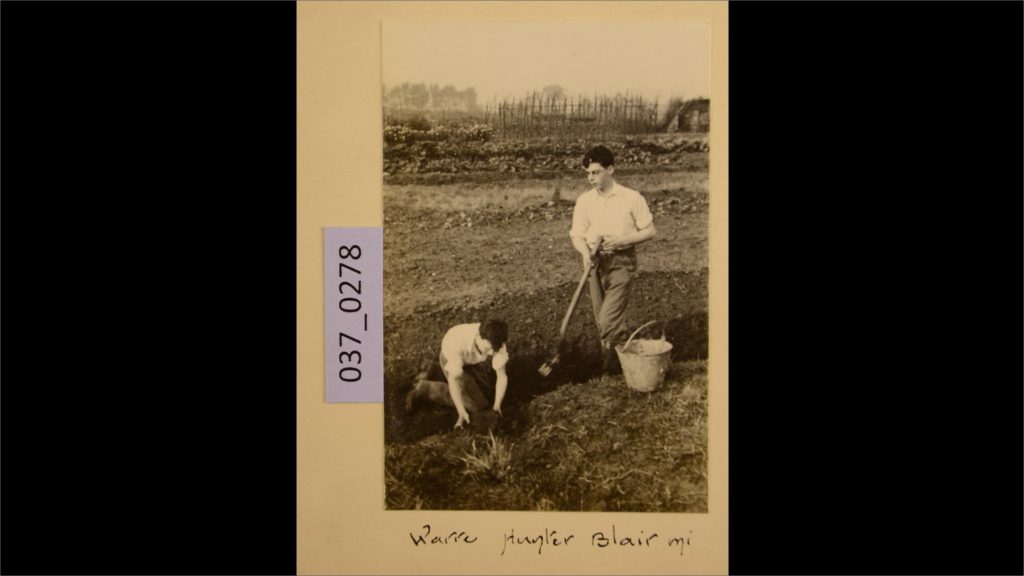

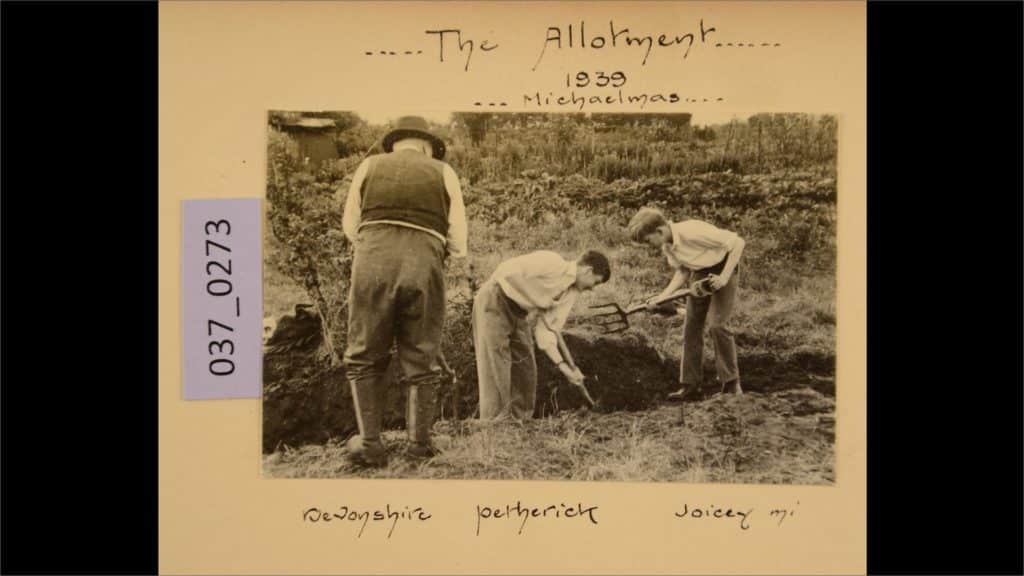

The World Wars gave the College another way to engage with gardening, with land in the Playing Fields given over to potato growth and each boarding house encouraged to develop an allotment. The ‘Dig for Victory’ campaign during the Second World War furthered the work begun under World War I, with further allotments created on previously uncultivated land in Carter’s Fields. The 1939 campaign from the British Ministry of Agriculture encouraged people to grow their own food during times of rationing and boys at Eton answered this call by tending to allotments in Eton Wick which are still in use, under the watchful eye of Mr Devonshire, gardener for C.R.N. Routh. It was an Old Etonian and keen agronomist, Lord Northbourne who was credited with introducing the term ‘organic farming’ to a wider audience in his book Look To The Land (1940) thirty years before Rachel Carson’s Silent Spring.

Amina Khan, Archives Assistant

[1] Maxwell Lyte p.10