From representations of individuals to things people held and used thousands of years ago, these objects bring forth an immediacy of the society and culture of people much like us, yet thousands of years ago. We recognise elements of our lives in the surviving materials from daily life, and aspects of our society in the civic officials and multiple classes, yet also confront the power imbued in these objects by the belief systems that unite all beings in ancient Egypt.

Although the divinely-appointed pharaoh was all powerful, owning all of the land and leading all military, religious and civic organisations, the pharaohs delegated the administration of their kingdom to high officials. Where these positions were initially given to members of the royal family, by Mesehti’s time there were many non-royal officials, albeit mostly from the upper classes. Mesehti was a nomarch, the overseer of a nome (a province or administrative district). He functioned in a role similar to mayor of Atef-Khent, the 13th Upper Egyptian nome, and his tomb was found in Asyut, the nome’s main town.

the imakh, beloved of his city, revered of his nome, Mesehti; the nomarch, chief of priests, great in his functions, noble in his dignity, Mesehti.

Mesehti’s tomb was discovered in 1893 and contained a number of models and two richly inscribed coffins. It is from these coffins that we know this figure’s name, and official role. The abundant grave goods, elaborate coffins and text that explicitly places him as a nomarch confirm that the indications of civic life we can glean from these objects relay to the upper strata of society.

Statue of Mesehti

Middle Kingdom, 11th Dynasty, ca.2000 BCE. Wood. [ECM 2617]

This statue would have been placed in Mesehti’s tomb as an anchor for his ka-spirit (life-force) throughout the afterlife. The Ancient Egyptians believed the soul had three parts, the ka, the ba, and the akh. Everyone possessed the ka and ba, but the akh was reserved only for those whose soul had been judged worthy by Osiris (the god of the afterlife) and Ma’at (the goddess of Truth, Justice and Balance). The ka-spirit was separated from the body at death and needed a statue to hold it and to receive the sustenance it required in the afterlife. The statue would be the focus of offerings given to sustain the deceased in the afterlife. It would also function as a surrogate if his real body was destroyed.

Statue of Mesehti

Middle Kingdom, 11th Dynasty, ca.2000 BCE. Wood. [ECM 2617]

Walking stick believed to be from the tomb of Mesehti

Middle Kingdom, 11th Dynasty, ca.2000 BCE. Wood. [ECM 2168]

Walking sticks were not just physical aids in ancient Egypt, they were important cultural symbols and markers of role and status. Paintings and illustrations show sticks being carried by aristocrats and officials as symbols of their office. They also show simpler, functional sticks associated with other professions. Tombs were often filled with multiple sticks; this plain wood walking stick was likely used as a physical support, and more elaborately decorated sticks would have been used to mark out Mesehti’s position as nomarch.

Carved from a single piece of wood, this walking stick shows signs of use, such as small cracks and rounded edges. Although not to the scale of the figure of Mesehti beside it, as it was not created purposely for funerary use but was used in life, you can imagine this man striding about his business in Asyut, his hand gripping the stick which supported his movements. Used as an aid in life, by being placed in the tomb it continued to serve Mesehti in death.

There would have been numerous other figures placed in a tomb. This painted, wooden offering bearer wearing a white dress, red headband, and carrying a casket, duck and driving a white calf, was made during the Old Kingdom, a time when figures of female offering bearers became more common in the tombs of the elite amongst the statues of the deceased, their family and servants. They were included to offer eternal sustenance with their provisions to the deceased in the afterlife, offering containers of food and drinks such as grain and beer. Carrying a casket on her head and accompanied by animals, she was based on women in towns who carried their loads in this way.

Offering bearer

Old Kingdom, 6th Dynasty, ca.2150 BCE. Wood, polychrome. [ECM 1591]

This figure is thought to be from the tomb of Hapikem in Mier (near Asyut, see map below statue of Mesehti): the inscription on the white casket is dedicated to Hapikem. A similar female offering bearer at the Ny Carlsberg Glyptotek in Copenhagen is believed to have come from the same tomb. She would have been placed facing towards the inside of the tomb, in the same way that those enacting the funerary cult would be positioned.

Offering bearer

Old Kingdom, 6th Dynasty, ca.2150 BCE. Wood, polychrome. [ECM 1591]

The inscription reads “Seal-bearer of the King of Lower Egypt, Sole Companion, Overseer of priests, the revered one, Hapikem”

Close up of offering bearer

Old Kingdom, 6th Dynasty, ca.2150 BCE. Wood, polychrome. [ECM 1591]

The following three objects are clustered together in an examination of the use of perfumes and cosmetics thousands of years ago. They are but three of an extraordinary number of objects relating to ablutions and makeup that have survived the ancient world, indicating this was a big part of daily and ritual life in society at the time. Cosmetic and hygienic toilette is a common part of life today which helps us envisage how these items would have been used in the past. They are familiar yet are rooted in the visual forms and symbolism of material culture in Ancient Egypt.

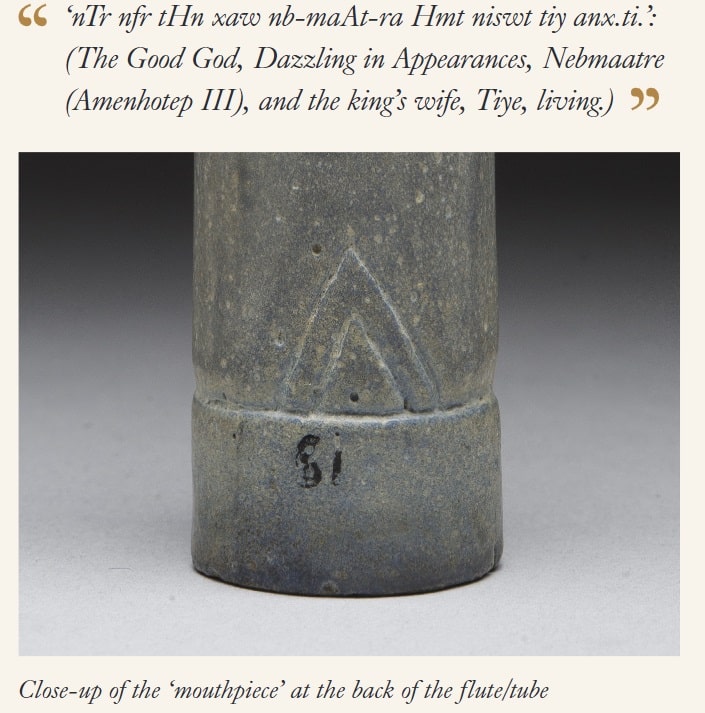

Kohl tube in form of reed flute

Mouthpiece

New Kingdom, 18th Dynasty, reign of Amenhotep III, 1390–1352 BCE. Faience. [ECM 1640]

Kohl tube in form of reed flute

New Kingdom, 18th Dynasty, reign of Amenhotep III, 1390–1352 BCE. Faience. [ECM 1640]

This kohl tube imitates a reed flute, drawing on the fertility associated with reed marshes on the banks of the Nile and on the sensuality associated with music and faience. Cosmetics, music and faience all have sensual aspects and are associated with the goddess Hathor. Carved from reeds, flutes were played frequently as a central part of religious and secular celebration, entertainment and worship. At the back of the tube there is a groove and triangle which indicates the mouthpiece of the flute.

Although inscribed to the king Amenhotep III, the inscription includes his queen Tiye, which emphasises the sensual femininity of this piece.

‘nTr nfr tHn xaw nb-maAt-ra Hmt niswt tiy anx.ti.’: (The Good God, Dazzling in Appearances, Nebmaatre (Amenhotep III), and the king’s wife, Tiye, living.)

Cosmetic spoon

With woman kneeling on skiff

New Kingdom, 18th Dynasty, 1375–1300 BCE. Steatite. [ECM 1793]

Also connecting cosmetics and music is this spoon whose handle depicts a woman, possibly a representation of a young Hathor, playing a lute. She is kneeling on a boat in a papyrus reed marsh. Both the handle of the lute and prow of the boat are in the form of a bird’s head. As described with the flute, music, cosmetics and papyrus are associated with Hathor, with an emphasis on fertility and beauty.

Cosmetic spoons were used to scoop the contents from larger containers for personal use or as an offering. Made from a single piece of steatite (soapstone) and worked into an ornate design, this spoon may have been used in offerings of precious lotions to the gods rather than everyday use. Spoons were also included in tomb furnishings for use in the afterlife.

Disc mirror

With handle in the female form

New Kingdom, early to mid-18th Dynasty, 1550–1400 BCE. Bronze. [ECM 1788]

Hand-held mirrors commonly had decorative handles in the form of a naked young woman. The woman with a crowning papyrus umbel (cluster of flowers) was a popular design for mirror handles during the New Kingdom. It connoted sensuality and fertility in the same way as earlier mirrors which represented the goddess Hathor on the handle. Hathor was associated, among many other things, with fertility, love, joy, eroticism and beauty; she was allied with Aphrodite by the Greeks and with Venus by the Romans.

X-ray of mirror

New Kingdom, early to mid-18th Dynasty, 1550–1400 BCE. Bronze. [ECM 1788]

The circular disc-shaped mirror of a highly polished, luminous metal suggests a reference to the sun or the moon. The form of both the handle and the mirror disc were significant. The X-ray analysis has shown that each part was individually cast, and that the metals were of differing densities. The mirror is connected by a rod projecting into the handle and is secured by a pin located above the umbrel.

This grouping of objects provide evidence of several more aspects of the everyday lives of Ancient Egyptians. They encompass architectural elements, bathing in the home or in religious ritual, and in this papyrus, an insight into social events.

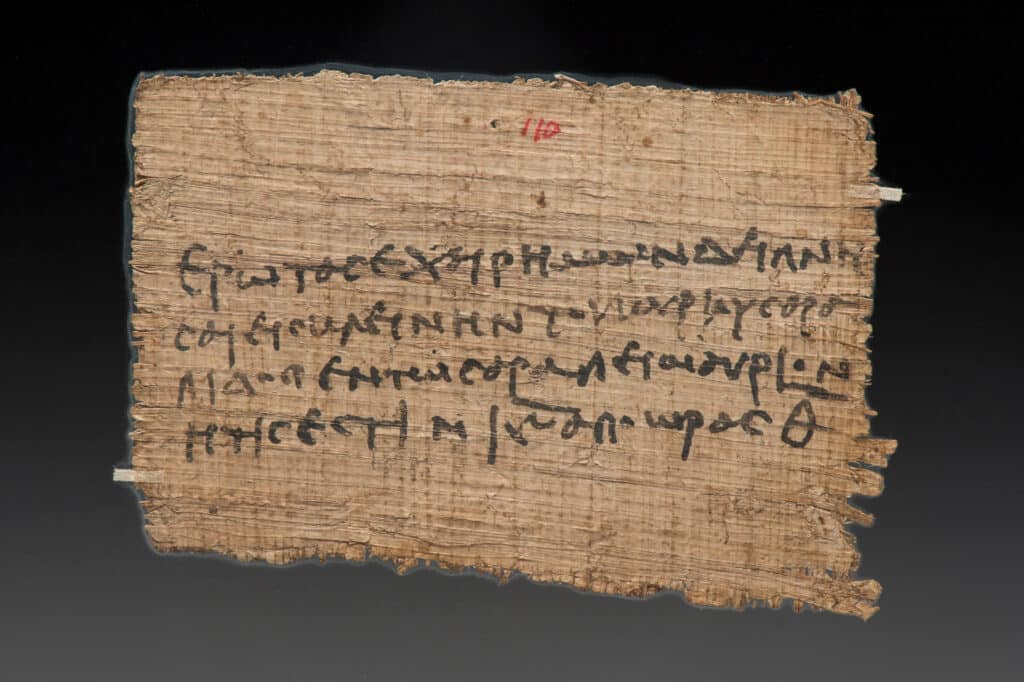

Dinner invitation, written in Greek, Roman Period, 2nd Century CE. Papyrus and ink. [ECM 2314]

Chairemon asks you to dine at the banquet of the lord Serapis in the Serapeion tomorrow, which is the 15th, starting at the ninth hour.

Translation of the Greek invitation

Butterfly cramp (dovetail)

New Kingdom, 19th Dynasty, ca.1294–1279 BCE. Wood. [ECM 1597]

This wooden cramp would have been used to connect stone blocks or strengthen wall joints. It is likely to have come from a temple building (most domestic dwellings were made from clay bricks, and only the temple would be built entirely from stone). It is inscribed with the name of the pharaoh Seti I ‘The Good God Menmaatra’ (nTr nfr mn-mAat-ra). Such wooden architectural pieces were often inscribed with the name of a god as part of an ongoing dialogue with the divine in an attempt to maintain balance (ma’at). In a cosmology where the literal and the spiritual are embodied together, engraved dovetails aid both the physical structure and mystical balance of the building.

The inscription would usually feature on the surface of the cramp that faced into the room; unusually the inscription here is on a narrow edge which would have been hidden within the wall. Although such inscriptions don’t necessarily need to be seen to have power, it is not very similar to other cramps inscribed to the pharaoh Seti I. Together with the unusual location of the inscription this makes it likely that this cramp was inscribed at a later date, perhaps to enhance its commercial value.

Butterfly cramp (dovetail)

New Kingdom, 19th Dynasty, ca.1294–1279 BCE. Wood. [ECM 1597]

When considering the treasures of ancient Egypt, jewellery, faience and metal vessels spring to mind. We do not often think of practical construction materials. Yet this shaped wooden object illustrates an ingenious building technique, the dovetail, which is still in use today.

Hsmny vessel with beak-shaped double spout

Close up

Old Kingdom, 2nd-3rd Dynasty, 2686–2160 BCE. Copper alloy. [ECM 1837]

Hsmny vessel with beak-shaped double spout

Old Kingdom, 2nd-3rd Dynasty, 2686–2160 BCE. Copper alloy. [ECM 1837]

A short and wide vessel with beaked spout, this is characteristic of a ewer (large jug) that the Egyptians called hsmny. Used to contain water for washing hands at mealtimes in the home, they were also used in ritual and funerary procedures. As with other everyday and ritual objects, ewers were placed in tombs to serve the deceased in the afterlife.

Hsmny vessel with beak-shaped double spout

Close up

Old Kingdom, 2nd-3rd Dynasty, 2686–2160 BCE. Copper alloy. [ECM 1837]

Analysis of this object supports the theory that it was placed in a tomb. The metal has mineralised with a corroded copper surface; in this corrosion there is evidence of different organic materials that were in contact with the vessel. For example, in some areas a pseudomorph (where the original mineral has been altered or replaced by another) shows the weave of a textile, suggesting that it may have been wrapped in linen or a similar fabric during burial.

This tiny figure, measuring under 8cm, offers both insight and mystery.

![String figure with glass beaded hair, First Intermediate Period, 2160–2055 BCE. [ECM 1843]](https://collections.etoncollege.com/wp-content/uploads/sites/5/2023/02/ecm1843_back1-684x1024.jpg)

String figure with glass beaded hair, First Intermediate Period, 2160–2055 BCE. [ECM 1843]

The figure comes from a small tomb in the necropolis of Beni Hassan, near the modern city of Minya in Middle Egypt. Beni Hassan is a rock-cut cemetery that sits on a sloping limestone hillside, today about a mile from the east bank of the Nile. It is most well-known for its grander tombs of 11th and 12th Dynasty officials, painted with bright scenes and located on the upper terrace. However, between 1902 and 1904 archaeologist, John Garstang (1876-1956), excavated 888 ‘shaft tombs’ on the lower level, considered to be a ‘middle class’ cemetery. On this lower level in tomb BH 420, this and two other dolls were excavated, three of only eleven objects which contrast to the larger number of funerary items found in higher class tombs, and the hundreds in the tombs of the Pharaohs.

It has previously been assumed the vibrant blue beads were made of faience, but stereomicroscopy has revealed they are made of glass, displaying characteristic bubbles. This identification is supported by XRF analysis which shows elements associated with glass (Ca, Si, Fe, K) with a copper colourant (Cu). This analysis has revealed a truly significant discovery: these beads are among the earliest known glass found in Egypt.

Garstang assumed this to be a child’s toy, which has since been disputed; the accompanying contents of the tomb did not indicate a child’s burial. This doll does not feature the sexual characteristics to function as a fertility figure, nor the realistic human features of a model or shabti figure to assist in the afterlife. The true purpose and use of this stunning doll remains a mystery.