The production of plants was complex, despite the fertile soil in Egypt. The river Nile flooded annually over the summer months; the entire years’ harvest had to take place before June. Produce then had to be stored; grain was kept in a granary, used to produce food and also given as workers’ pay. Produce was also stored in clay vessels.

Certain plants in particular were associated with the gods, and were prestigious in their symbolism and use. Papyrus, Cyperus papyrus, was a symbol of youth and joy and used to make paper, rope, baskets and clothing. It was named after pa-en-per-aa, meaning ‘belonging to the pharaoh’, a high status. Papyrus is extensively represented across objects, art and architecture.

It appears frequently in a stylized form either as a single stem with bud or flower or in a series imitating the dense reed beds. The fields of reeds in the marshes along the Nile were habitats for many birds and animals, which are often depicted in artwork in river and hunting scenes. Draining of swamps and over-cultivation mean this plant is no longer grown in the wild along the Nile.

Contract of employment

Roman Period, 188 CE. Papyrus and ink. [ECM 1616]

This papyrus records the contract between Amois, the tenant farmer in a vineyard and reed plantation in Talao (a village near to the city Oxyrhynchus) and the owner Apion, a gymnasiarch (civic official). The long-term lease, or misthōsis, outlines the work to be carried out by Apion: gathering and preparing reeds for use in the vineyard, and farming and harvesting the vineyard. The contract was written in Greek on papyrus during the reign of Emperor Hadrian. Legal documents used papyrus and continued to be written in Greek after Egypt came under Roman rule.

‘…the uprooting of reed, its transportation to the customary place, the sweeping of leaves, the cutting and transportation of these outside the mud‐wall to suitable places, [d]igging, trenching, vine-layering in the necessary places, the cutting of fresh reed for the creation of stakes, the creation of stakes—the landowner supplying reed and sufficient bark – continual irrigation and weeding, hoeing, the collection of shoots, the separation of plants [and] tying up of shoots, the collection of leaves, and he will p[articipate in] the vintage and will mix Pelusi[an wine]’

Extract from the Greek papyrus listing the tasks for Amois, translated by Daniel Dooley, Johns Hopkins University

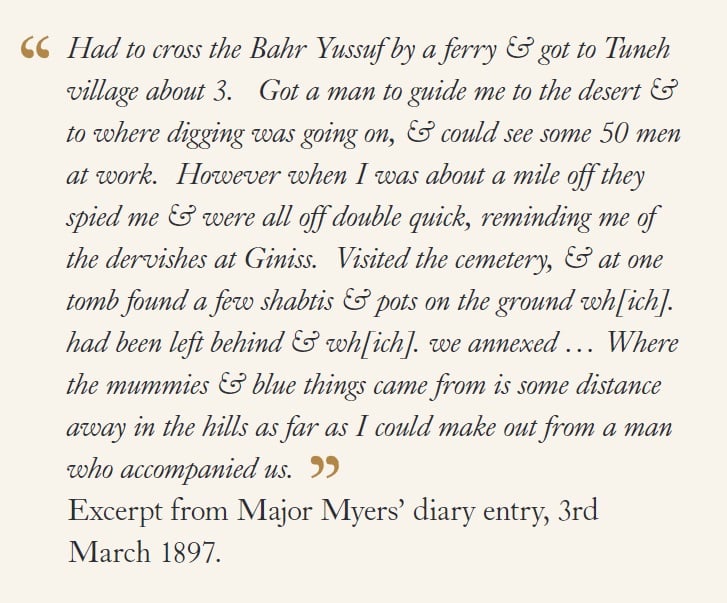

Faience tile

Old Kingdom, 3rd Dynasty, Reign of Djoser, 2667–2648 BCE. Faience. [ECM 1836]

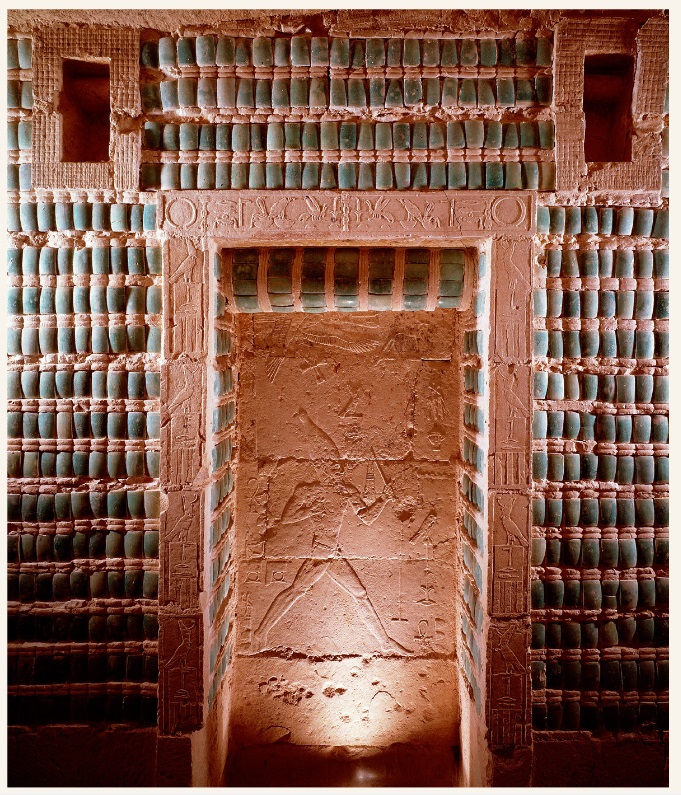

The papyrus plant was frequently depicted in decorative schemes across significant buildings such as temples, palaces and tombs. In addition to palms and grasses, papyrus was used in basketry, and representations of woven matting adorned temple and tomb walls, relating to the mythic connection of papyrus with life, eternity and the afterlife. Both the portrayal of papyrus and the use of blue faience evoked the renewing power of the Nile.

It is believed that this tile was used as part of imitation reed matting, one of the 36,000 tiles that decorated the walls and doors of the Step Pyramid of Djoser and the enormous surrounding complex.

Inside chambers of King Djoser’s pyramid

In Saqqara

Image Credit: BRIAN BRAKE / SCIENCE PHOTO LIBRARY

Inside the chambers of King Djoser’s pyramid in Saqqara. He reigned in Ancient Egypt from c. 2635 to 2610 BCE. His architect Imhotep designed the first (step) pyramid in Egypt.

The earliest form of paper, papyrus was invented in Ancient Egypt using the Cyperus papyrusa plant, as early as 3000 BCE. A reed-grass with triangular stems that were peeled and cut into strips, layered and set, the production of paper was a skilled and expensive process and therefore papyrus was used primarily for important documents.

The lotus is also emblematic, steeped in symbolism that was abundant in its representation. It appears in two forms, the blue lotus, Nymphaea caerulea, and white lotus, Nymphaea lotus. Most commonly depicted was the blue lotus, an important symbol of regeneration linked to the cycle of the sun and the endurance of life, as the flower closes at night and opens again each morning. It also blooms all year round. The white lotus blooms at night linking it to the lunar cycle.

Chalice in form of a blue lotus

New Kingdom, mid–18th Dynasty, 1450–1400 BCE. Faience. [ECM 1578]

Blue lotiform chalices are principally for cult or votive use in offerings in temples and tomb contexts. These ceremonial vessels would have contained wine as an offering to the gods. Wine was a high status drink: practically, vineyards took a lot of maintenance and great care was required to harvest grapes and create wine; symbolically, wine was believed to be a gift from the gods. Wine was associated with Osiris and the goddesses Bastet, Sekhmet and Hathor.

Chalice in form of a blue lotus

Third Intermediate Period, 22nd Dynasty, 945–715 BCE. Faience. [ECM 1676]

This chalice is decorated with multiple lotus flowers. The base and stem are decorated with flowers pointing downwards. Emerging from the top of the stem, which can be seen as the stem of the flower, one lotus with pointed, triangular leaves circle the base of the cup. Above this are two lines either side of a wavy pattern which depicts water. The top half of the cup has numerous lotus flowers and petals stretching up towards the rim.

The cup was made in two parts, the bowl and the stem, which were then connected using faience paste. The bowl was mould-made and the stem modelled around a cylinder. With its fluted shape, it is believed that the decoration would have been painted when the vessel was placed upside down on the rim of the cup to dry.

Chalice in form of a white lotus

New Kingdom, late 18th–19th Dynasty, 1352–1069 BCE. Faience. [ECM 1579]

On these chalices the triangular petals are marked out with black lines. The white lotus chalice is distinguishable from the blue lotus chalice as the flower mimicked by the cup is broader. In other examples of lotiform vessels, the petals are sometimes depicted with incised lines or in relief.

Chalice in form of a white lotus

View of decoration on base

New Kingdom, late 18th–19th Dynasty, 1352–1069 BCE. Faience. [ECM 1579]

Lotiform chalices (cups shaped and decorated as the lotus flower) were first made in the Eighteenth Dynasty, often in faience. The blue-green of faience was associated with life and regeneration, which matched perfectly with the symbolism of the lotus plant. The blue lotus was a symbol of regeneration and the daily renewal of creation as it was connected to the solar cycle, blooming each morning and remaining open throughout the day. The Ancient Egyptians found powerful religious meaning in the behaviours and activities of plants and animals in nature.

The other lotiform was the white lotus, although these were less common. These would also have had a function as votive offerings, used as drinking vessels containing wine or milk in worship of the cow-headed goddess Hathor. There is also evidence of white lotiform chalices in royal and domestic contexts. Whether as a votive chalice, a stately vessel or domestic cup, the white lotus would evoke rejuvenation and rebirth, associated with the flower’s lunar bloom cycle.

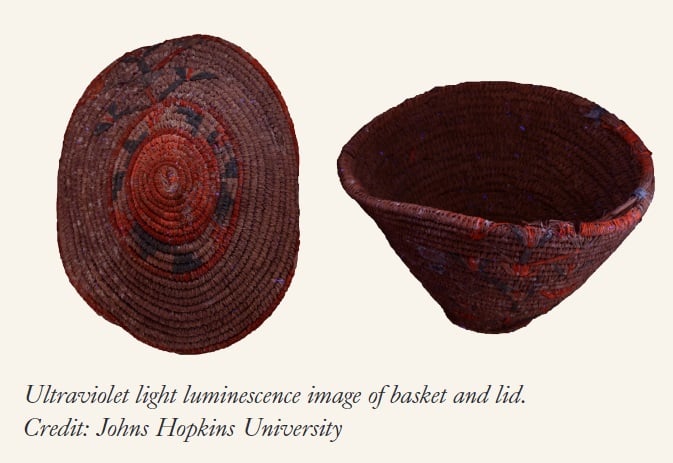

Basketry is an ancient form of manufacture that was found in objects and decoration in domestic, religious and funerary contexts. Baskets were used to contain an assortment of things from grain and food to cosmetics and jewellery. When in a tomb context, these items would be offerings to sustain the deceased in the afterlife. The good quality of this basket indicates it was preserved in a tomb.

Conical basket with lid, New Kingdom, 18th Dynasty, 1550–1292 BCE. Basketry, pigment. [ECM 1889]

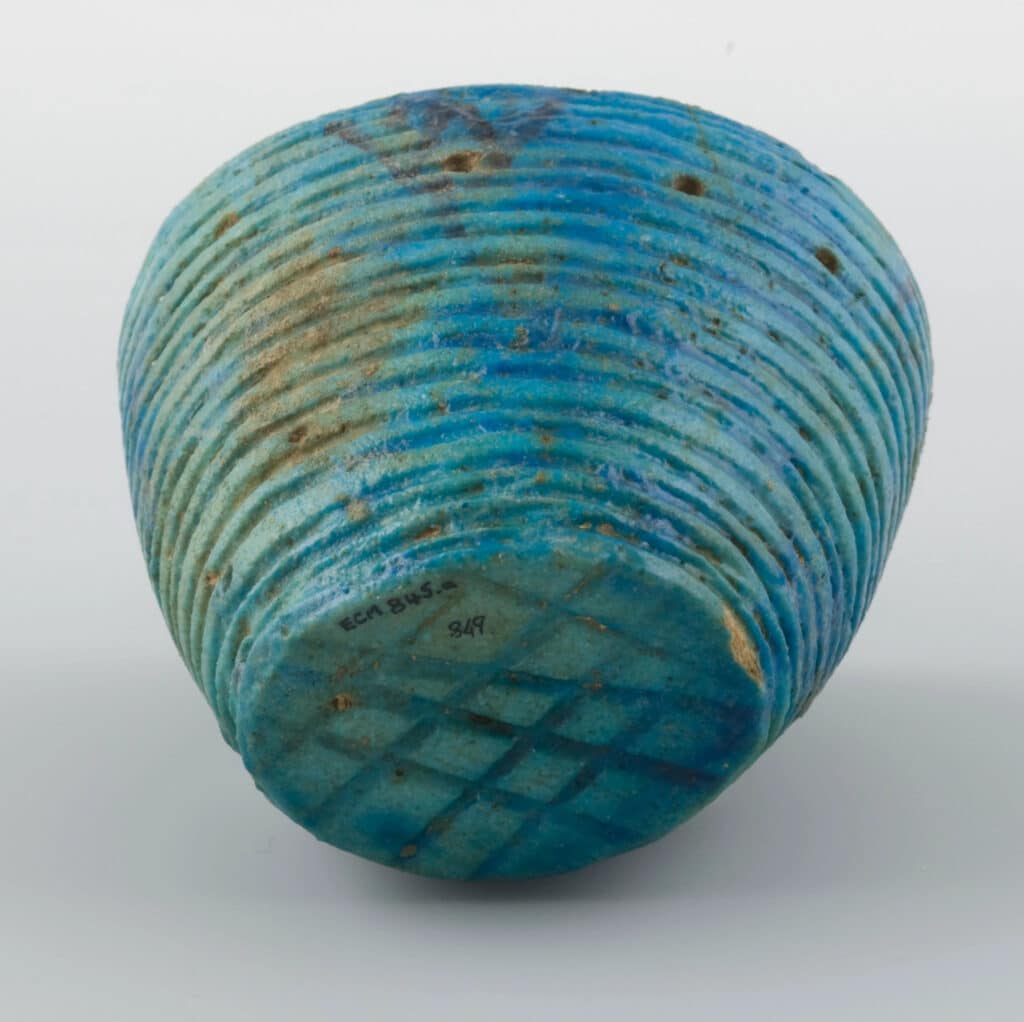

A recurring theme in Ancient Egyptian material culture is to mimic basketry in different materials. The coiled basketry work here is displayed alongside a faience basket and lid that mimic the technique of the woven plant fibres. We can also see how the basketry motif has been replicated in other materials with the use of blue faience tiles copying reed matting.

Vessel in the form of a basket with lid, New Kingdom, 18th Dynasty, ca.1450 BCE. Faience. [ECM.845]

It is thought that the few known examples of faience basket all came from one workshop at Tuna-el-Gebel, renowned for quality faience. Major Myers was frequently in Egypt in the mid-1890s when a large amount of Egyptian faience was re-discovered at Tuna el-Gebel. He purchased several faience objects which had come from ‘Tuneh’ (as Myers wrote in his diary) through dealers such as Carl Reinhardt.