Mortuary practices and the funerary cult were a central part of the interaction between humans and the divine. The Book of Amduat is a funerary text and was intended to be a guidebook for the deceased, to assist them on their journey to the afterlife. The text is written in hieroglyphs, a system of writing that was reserved mainly for use in religious and funerary contexts. Originally produced on the walls of royal burial chambers, the text is divided into twelve parts representing the twelve hours of the sun god Re’s progress through the netherworld.

There were a number of major gods that were worshipped in dedicated, state-owned temples. Smaller deities were then supported for their specific attributes by towns, in local temples or shrines. A larger range of gods were then worshipped by individuals. Personal piety usually related to a particular need for the influence or support of a god’s specific magical powers.

Each god had its own personality, forms, roles and areas of influence; some, such as Thoth, had multiples of these. The Ancient Egyptians depicted their gods both anthropomorphically (having the characteristics and appearance of human beings) and zoomorphically (having the characteristics and appearance of animals). The attributes of gods also developed over time as new theologies and cultures were embraced.

Figure of Thoth in baboon form

Late Period, 664–332 BCE. Egyptian Blue. [ECM 722]

The god Thoth is a good example of a deity whose mythology evolved over time, had multiple forms and served a variety of roles in both the divine and human worlds. Thoth is a lunar deity, a god of the moon, and a lunar crescent is likely to have been attached at the break on the top of this figure’s head. In Thoth’s mythology, he is said to have restored the left eye of Horus (identified as the moon; Horus’ right eye was the sun).

Thoth is also the god of writing and wisdom, thought to be the inventor of writing and hieroglyphs, and acts as scribe to the gods. According to myth, Thoth gave Isis the words that enabled her to resurrect her husband and rightful ruler of Egypt, Osiris, thereby enabling her to conceive Horus.

Originally thought to be associated with Thoth as a lunar deity, the baboon form came to be associated with Thoth’s role as god of writing and patron of scribes. Miniature figures of the god were sometimes included in writing kits.

Figure of Thoth in baboon form

Late Period, 664–332 BCE. Egyptian Blue. [ECM 722]

Figure of Thoth in human form

Ibis-headed with Jackal-headed feet

Late Period-Ptolemaic Period, 664-30 BCE. Faience [ECM 1587]

Thoth’s two other forms are that of an ibis and an ibis-headed human, as seen here. His jackal-headed feet are representations of souls of Hermopolis. The city Khmunu (Khemenu) was a centre of the cult of Thoth; the Greeks associated Thoth with Hermes due to shared attributes as gods of magic and writing, and renamed the city Hermopolis.

Figure of Thoth in human form

Ibis-headed with Jackal-headed feet

Late Period-Ptolemaic Period, 664-30 BCE. Faience [ECM 1587]

Figure of Isis

Suckling Harpocrates

Late Period, 26th Dynasty, 664-525 BCE. Faience. [ECM 1717]

The goddess Isis is shown here as a mother suckling her son Harpocrates (a Greek adaptation of the Egyptian child-god Horus). This form demonstrates two significant aspects of Isis’ role. As a protective mother she represents fertility and successful pregnancy. As mother of Horus she legitimises the divine rule of the human kings of Egypt: kings were regarded as the incarnation of Horus.

To further this connection and extension of divinity, Isis is depicted here wearing her throne-shaped crown. The Egyptian word for throne was st, which was also the name and symbol of Isis. As a manifestation of Horus, when the king sat on the throne, he was imagined to be sitting on the lap of his mother, Isis, and derived some of his power from her. The cult of Isis became particularly popular during the Third Intermediate Period, ca. 1070 BC – 664 BC, a time of considerable political instability.

Figure of Isis

Suckling Harpocrates

Late Period, 26th Dynasty, 664-525 BCE. Faience. [ECM 1717]

Figure of Sakhmet

Late Period, 26th Dynasty, ca.600 BCE. Faience. [ECM 1716]

Sakhmet (or Sekhmet) is one of the earliest deities in the pantheon of Ancient Egypt. She was a goddess of fury, plague and destruction, and protector of women, and her amulet would have been worn for protection. A hole pierced through the back of the object implies it could have been worn like a necklace yet the figure is relatively large which suggests it could have been used as a votive offering.

She is depicted with the head of a lioness, indicating her strength as well as her potential violence. Sakhmet’s name is derived from the Egyptian word Sekhem, which can be translated as ‘power’ or ‘might.’ She wears the sun disc and uraeus (a sacred cobra), which are both symbols of divinity and royalty, and associate her with her father, the Sun god Ra (or Re).

Material culture from Ancient Egypt is abundant with symbolic representations and manifestations of the gods, in forms that carried the powers and qualities of the deity depicted. These enabled the deities to have multiple roles in religious and everyday life. For example, amulets were worn or placed on the body, in order to allow the secure transfer of these powers. They were sometimes placed in the bandaging of mummified bodies. Figures were also used with a votive function and left as an offering in a temple or shrine, as a form of communication with the gods. The materials and colours used for these representations also had symbolic meaning and their own magic.

Pectoral depicting Osiris in the sun-barque

New Kingdom, Ramessid Period, 1295-1069 BCE. Faience. [ECM 814]

This vibrant blue faience pectoral, depicting Osiris enthroned on the sun-barque, was intended to be worn around the neck, so that it sits on the chest of the wearer (hence ‘pectoral’). Such items might be worn in life, or after death; with its iconography of Osiris it is likely this was a funerary item. The bright blue glaze was linked to rebirth.

In Egyptian mythology Osiris was the first king of Egypt who was murdered by his jealous brother Seth. Isis, his consort, reassembled his dismembered body and resurrected him, conceiving Horus by her husband before he took up his place as god-king of the underworld.

Here, on this pectoral, Osiris is shown on the sun-barque, reflecting his union with Ra, who, in the perpetual cycle of life and death, journeys to the underworld in the barque each night and unites with Osiris. Osiris is flanked by Shu and Tefnut. Shu is the god of light and air, symbolic of creation, the distinction between day and night and between the domains of the living and the dead. Shu and his sister Tefnut are shown holding an ankh, the symbol of life. Tefnut is the goddess of moisture, who was strongly associated with both sun and moon, usually depicted as a lioness or a woman with the head of a lioness. She is wearing the sun disc and uraeus, a symbol of power.

Figure of kneeling priest of Bastet

Third Intermediate Period-Late Period, 22nd-26th Dynasty, 945-525 BCE. Copper alloy. [ECM 1533]

This figure is clearly marked out as a priest: the kneeling position of worship, skull cap and shendyt kilt are all typical depictions of a priest. He holds a representation of the goddess Bastet in her lioness form. On the priest’s back are dedicatory hieroglyphs to Bastet (see inset). Likely a votive figure, this would originally have been paired with a statue of the goddess.

Bastet is commonly depicted as a cat, often identified with the beneficial powers of the sun, and was the patroness of pregnant women. However, until the end of the second millennium BCE, she was shown as a lioness and had warrior attributes.

Back of priest

Third Intermediate Period-Late Period, 22nd-26th Dynasty, 945-525 BCE. Copper alloy. [ECM 1533].

Image Credit: Johns Hopkins University.

Multispectral imaging was used to reveal more clearly the hieroglyphs on the priest’s back in their fullest detail.

Left column: “Bastet, who gives life, Pa-sheri-Amun-djedu (the name of the priest).”

Right column: “Bastet, who gives life! Iret-en-Atum (feminine personal name). Her son, Meny, Vindicated.”

Naos-sistrum

Depicting the goddess Hathor

Third Intermediate Period or later, 22nd Dynasty or later, 1069 BCE or later.. Faience [ECM 1693]

This musical instrument features the cow-headed goddess Hathor. One of the most important and enduring figures in the Ancient Egyptian pantheon, her name translates as ‘House of Horus’, reflecting an intimate and protecting role towards Horus and the pharaoh. She was originally conceived as a personification of the Milky Way, which was itself understood to be the milk that flowed from a heavenly cow. Hathor was associated with music and dance, and used a sistrum to drive away evil and motivate good. The hieroglyphs invoke the magical powers of Bastet; both Hathor and Bastet have nurturing and avenging powers.

It may be that this sistrum was used in temple rituals to appease the more destructive aspect of their powers. The naos (shrine)-sistrum would originally have had two bars strung with metal discs that would rattle and would have been for use in sacred ritual. The sistrum is also surmounted with the goddess Ma’at, the personification of the idea of cosmic order, as a stabilising power, to offset any potential imbalance between the protective and aggressive attributes of the goddesses Hathor and Bastet.

![Cloisonné pectoral depicting Horus and Seth. Middle Kingdom, 12th Dynasty, 1985-1773 BCE. Electrum, lapis lazuli, carnelian, feldspar. [ECM 1585]](https://collections.etoncollege.com/wp-content/uploads/sites/5/2023/02/ecm_1585_a-1024x622.jpg)

Cloisonné pectoral depicting Horus and Seth. Middle Kingdom, 12th Dynasty, 1985-1773 BCE. Electrum, lapis lazuli, carnelian, feldspar. [ECM 1585]

This stunning pectoral demonstrates the importance of jewellery in Ancient Egypt as decoration but also as objects with significant magical purpose. Exhibiting the technological advancement of metalwork in the Middle Kingdom, every element of its design, from the iconography to the colours and materials used, is loaded with symbolism and evokes power.

It suggests the opposing forces of chaos and violence, as represented by the god Seth (also known as Set, depicted in the set-animal form, similar to a jackal), and of harmony and maat, as represented by Horus (son of Osiris, depicted as a sphinx with falcon head). While these forces are opposed, there is a balance or dynamic equilibrium. This balance is reflected in the composition of the piece, where the overall impression is one of symmetry. In the centre is the goddess Hathor or Bat (another cow-headed goddess who is eventually merged into Hathor) whose horns extend upwards to the sun disk, which in turn is flanked by uraei (cobras). Eyes of Ra (also known as Eye of Horus) either side of the cobras link to Horus and Seth mythology and together support the theme of the restoration of symmetry, balance and wholeness.

The colours and materials used further imbue this pectoral with magical significance. Gold was considered a divine metal. Analysis confirms that this gold-silver alloy, likely electrum, has major peaks of gold with peaks of silver. Inset into the metal were precious stones in the ancient cloisonné technique. Lapis lazuli was second only to gold and silver; the vibrant blue represented the heavens. It was expensive and mined and imported from what is now Afghanistan. The metal was inlaid with other stones including carnelian and feldspar.

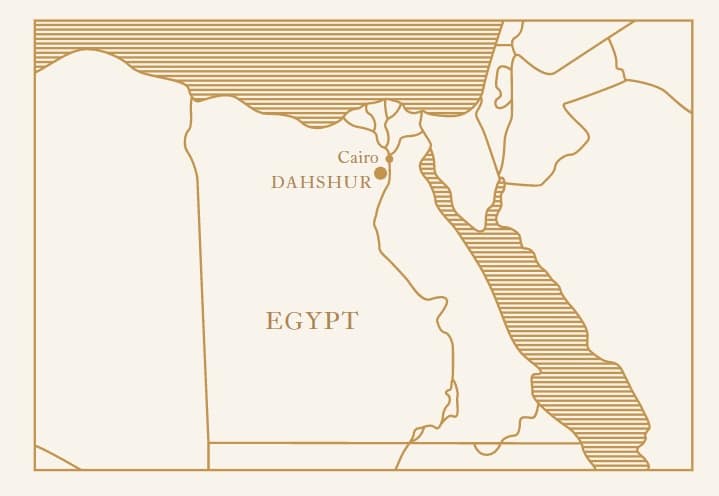

Research has connected this piece to a funerary context, most likely relating to the tombs at Dahshur. Pectorals similar to this were found in burials of royal women at Dahshur, and the princess Sithathor, ‘daughter-of-Hathor’ (possibly a daughter of Sensuret (Senwosret) II), was buried there. It is thought that the pectoral belonged to her, given the representation of Bat/Hathor. Additionally, an entry in the diary of Major Myers, the former owner of the pectoral, suggests this pectoral was purchased in Cairo not long after the tombs at Dahshur were excavated.