The coronation of King Charles III earlier this year was the most recent example of how the public engages with ideas of kingship and the right to rule. Today we mark such occasions with a bank holiday, but historically, the issue of succession could be a bloody affair, and claims to inheritance would need to be supported by evidence as well as allies. Genealogies were (and still are) one manifestation of a desire to untangle someone’s family history – and programmes such as Who Do You Think You Are suggest that ancestry continues to capture the public imagination.

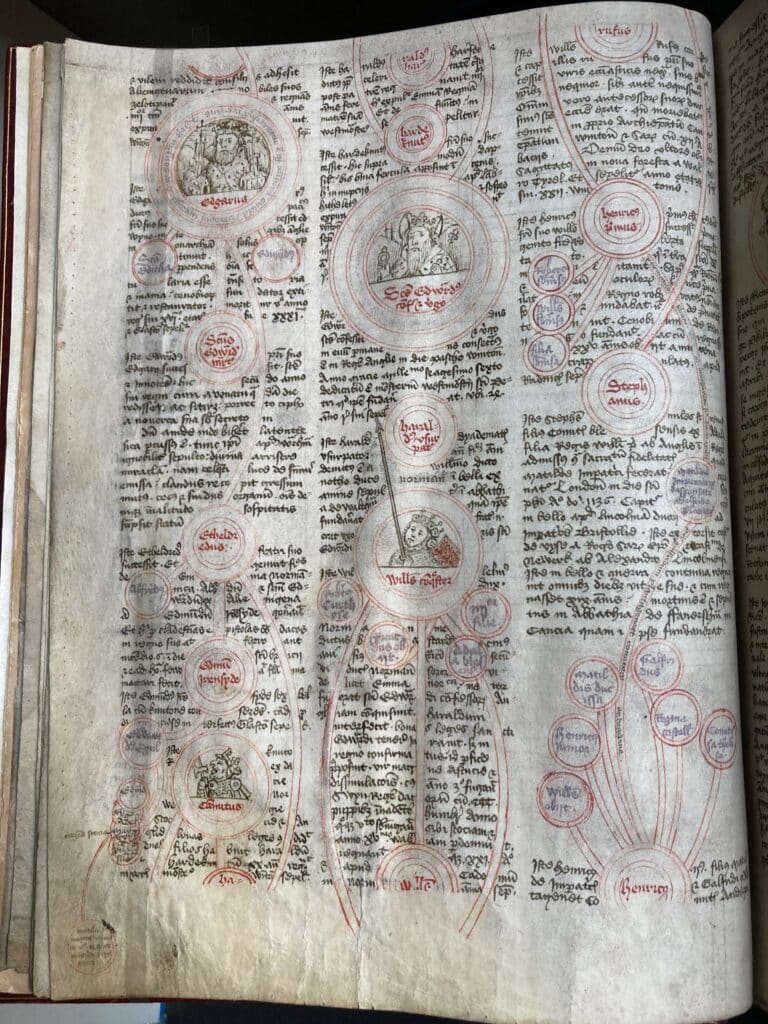

Interest in genealogy is well represented at Eton College Library, from medieval rolls to 19th-century heraldry treatises. Currently on display is a 15th-century copy of a universal history written a century before (MS 213). It is accompanied by four pages of an illustrated genealogy of English kings, starting with Ecgberht (r.802-839) and finishing with Henry VI. What makes this copy unique are the portraits of individual monarchs, which unusually include personal narratives of each king rather than simply portraying depersonalised crowned individuals. [1] Another interesting feature of this genealogy is that it presents a line of succession supporting the Lancastrian claim to the throne – only at a second stage was the Yorkist heir Edward IV added at the very bottom of the last page. This is an example of how genealogical documents could act as political propaganda during the War of the Roses, in this case providing arguments in favour of the Lancastrians under the guise of an authoritative framework.

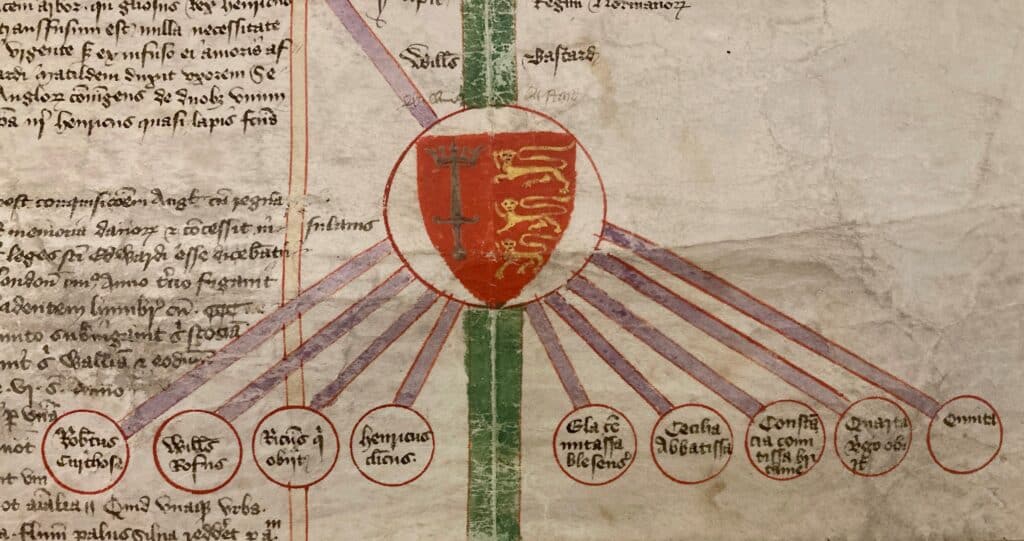

This format, showing roundels accompanied by text, is common in medieval genealogies, and we find it again in this 15th-century roll (MS 191), which is about 6 metres long in its entirety. In this case, the genealogy not only portrays lineage but also makes a more subtle case for legitimacy. Where there is no traceable kinship, we still see lines connecting families: these relationships were not understood in a biological sense, but were rather ‘organised, rearranged, and reconstructed as needed [since] blood served primarily as a metaphor naturalizing an alliance’. [2] Furthermore, if in the aforementioned chronicle King William is called ‘the Conqueror’, here it is ‘the Bastard’.

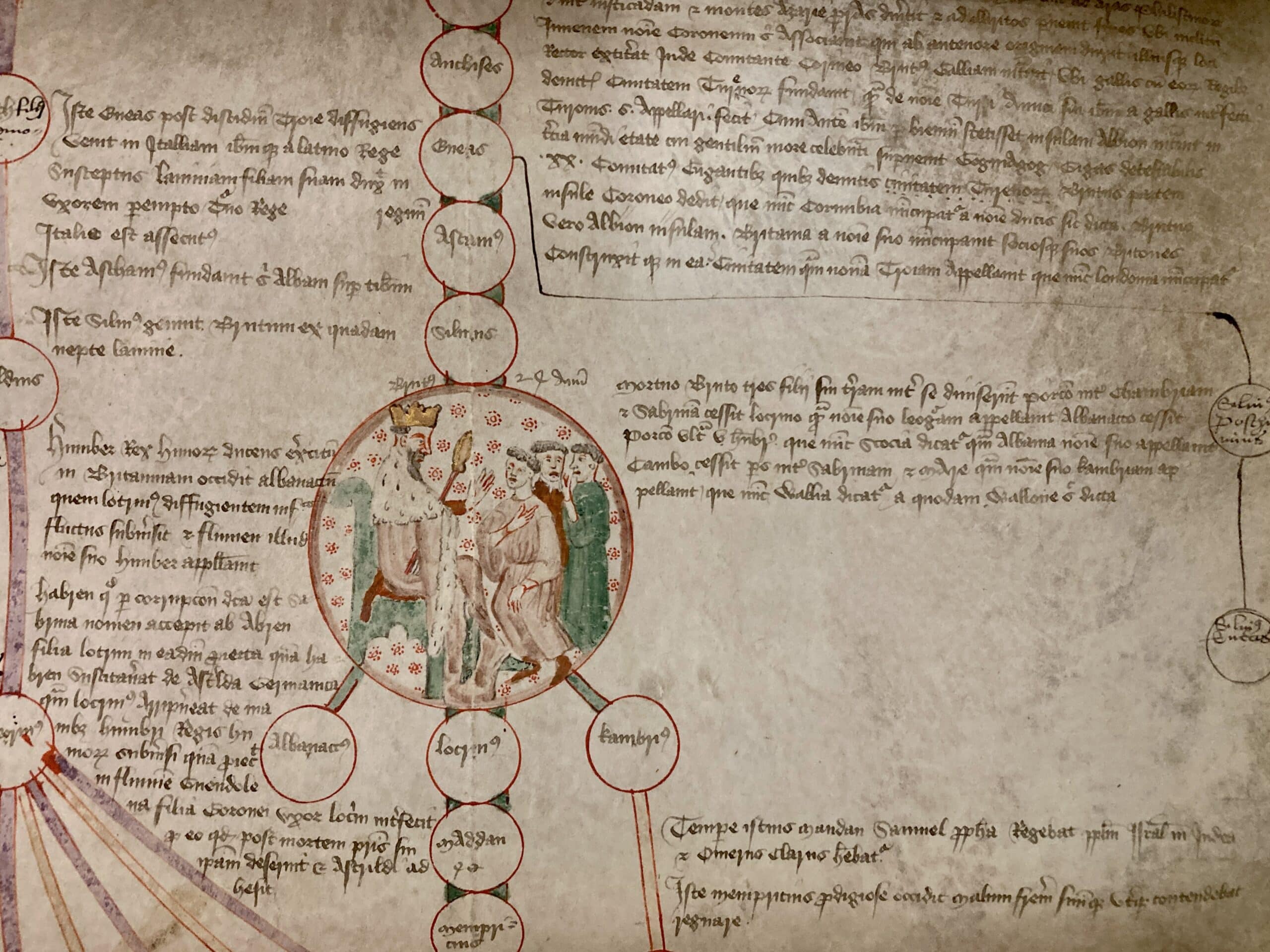

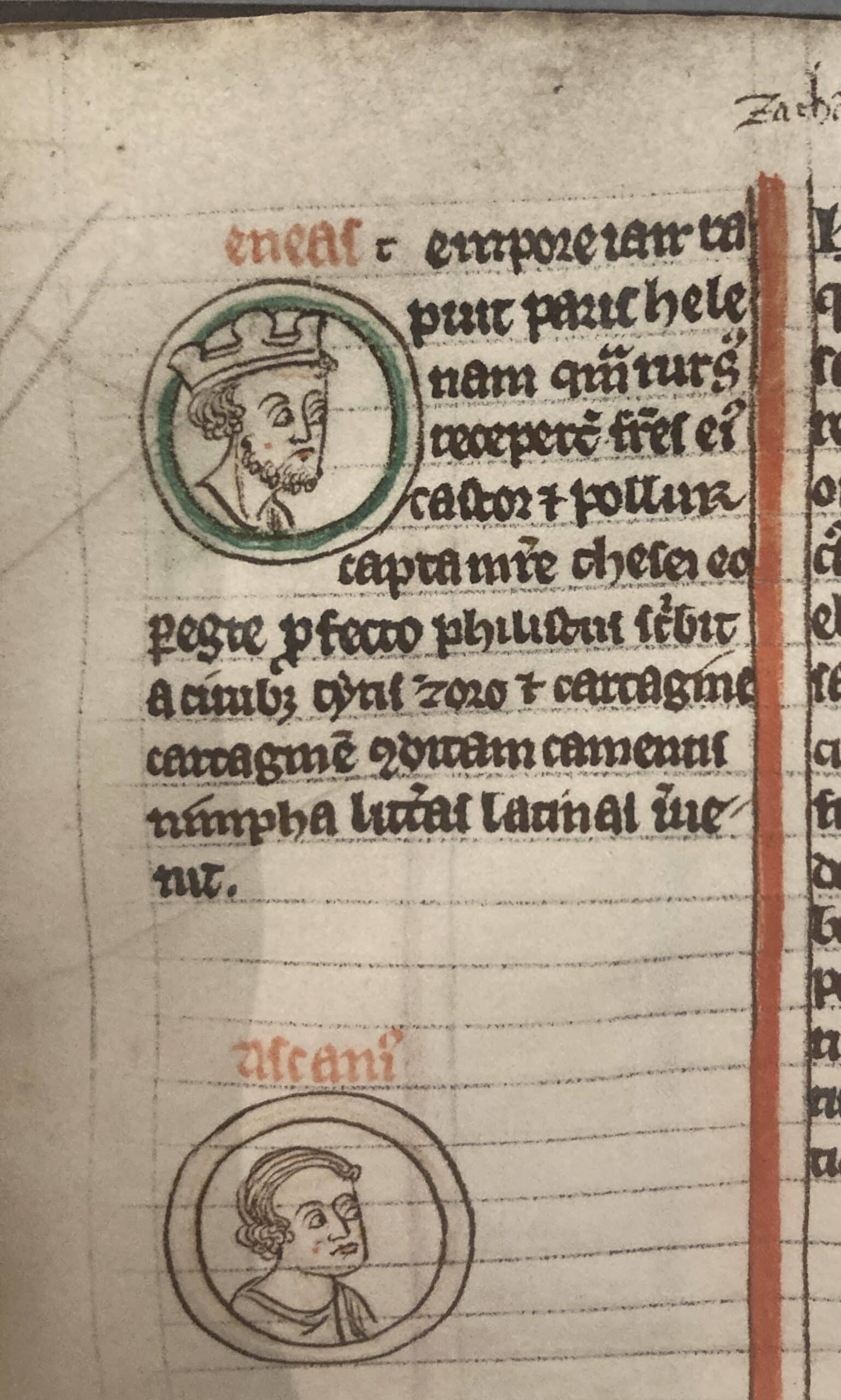

There is also something else going on here: since ‘history’ was conceived as having a beginning and end, most medieval Christian genealogies begin with the creation of the world and the first king: Christ. They then interlace other narratives, including characters now known to be fictional, in order to establish a particular origin story of the British people. For instance, the roll (MS 191) also includes Brutus, descendant of the Trojans and legendary first king of Britain. Similarly, a 13th-century ecclesiastical genealogy in College Library (MS 96) includes another Trojan prince, Aeneas, and his son Ascanius within a descent from Adam to Christ. Both books therefore argue for a connection between British kings and the ancient city of Troy via the foundation of Rome – a common theme in European ‘nation’ mythmaking.

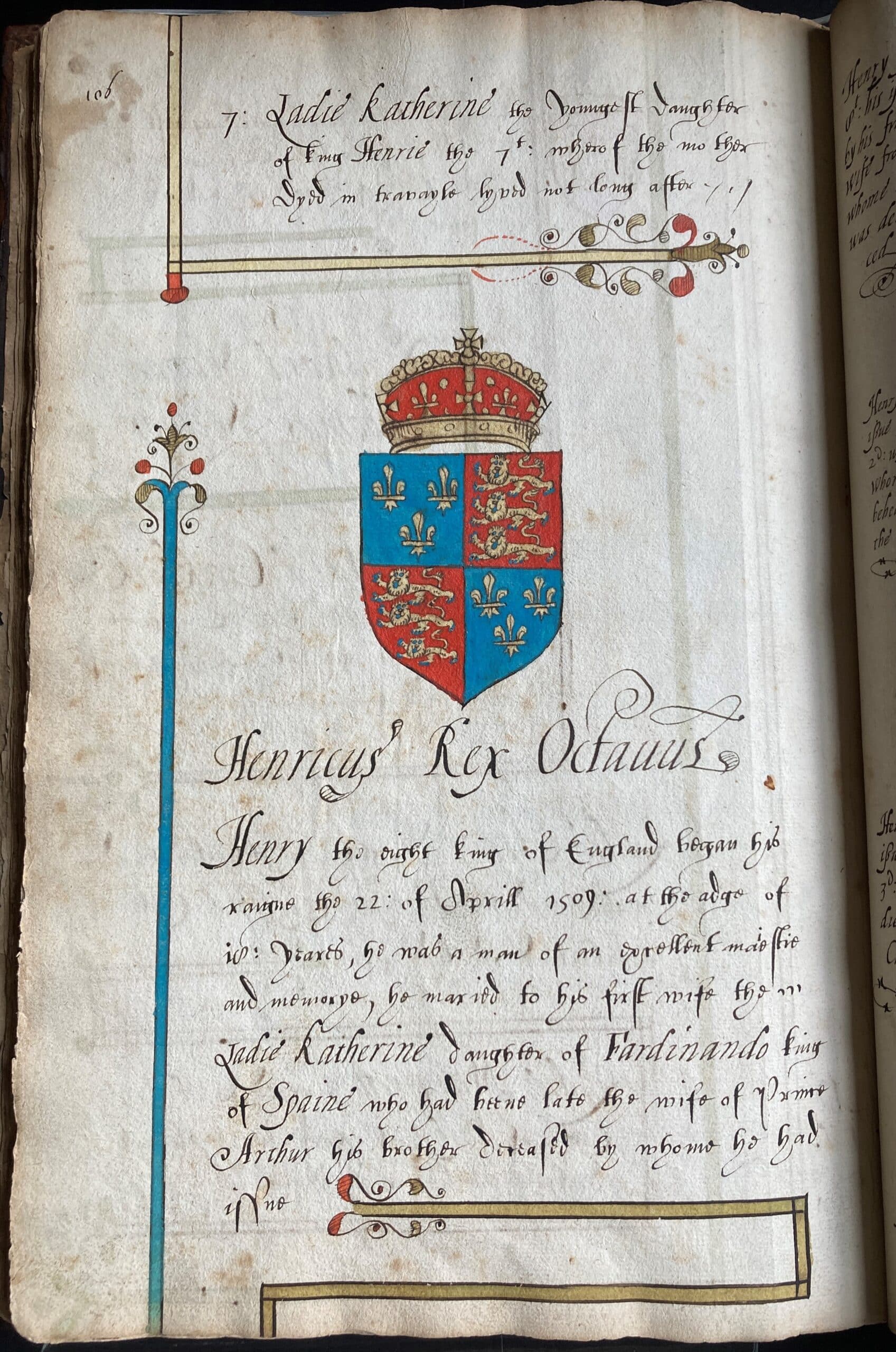

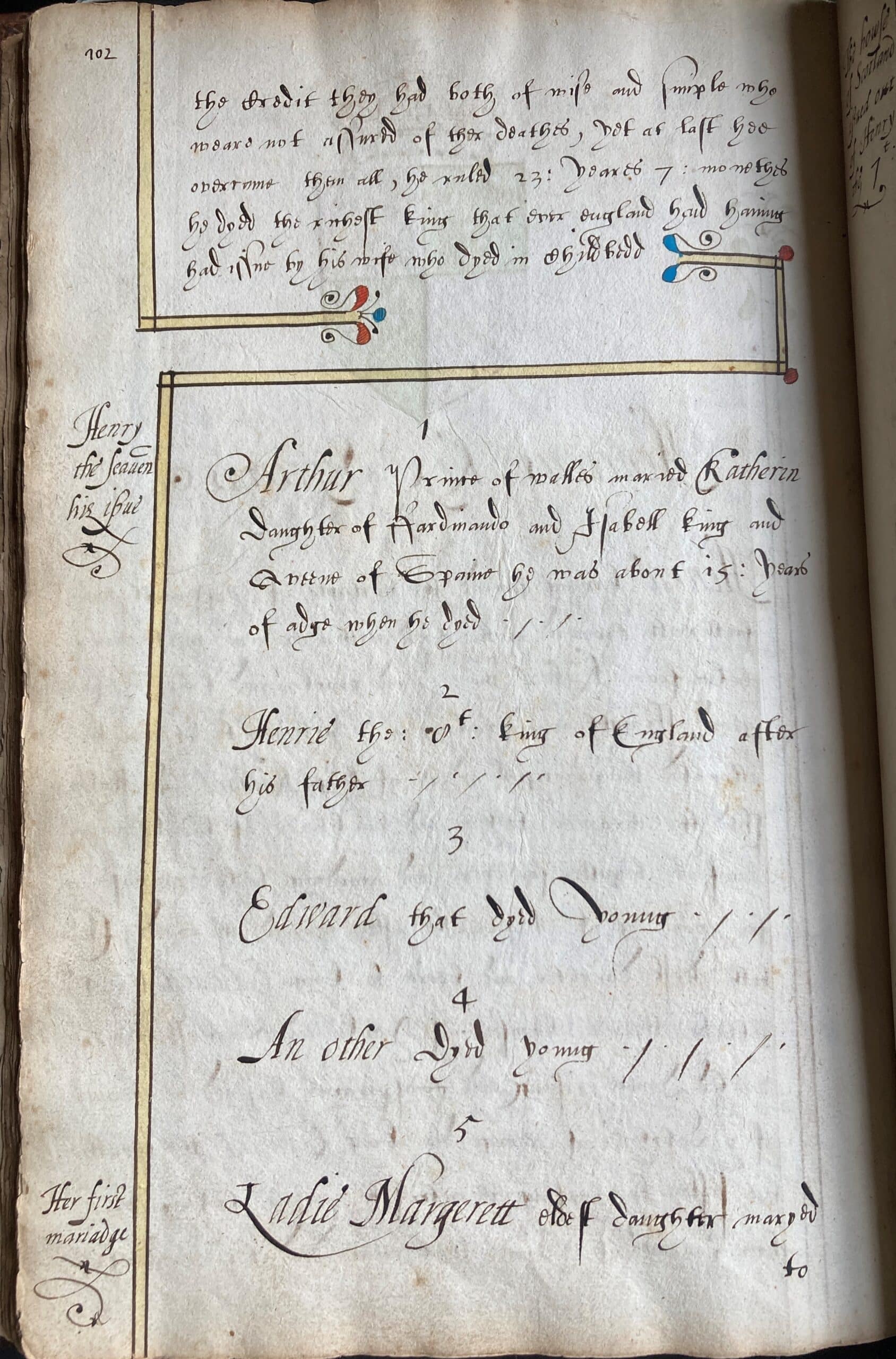

Claiming legitimacy by recalling the past is a trend that continued in later volumes as well. The 17th-century genealogy pictured below (MS 349) connects William the Conqueror to James VI/I, and within the Tudor line, Henry VIII is described as ‘a man of an excellent maiestie and memorye’ who married Katherine, daughter of the King of Spain and former bride to his older brother. Although Henry is one of the most famous English monarchs, he did not become heir to the throne until the death of his brother. Following the conclusion of the War of the Roses, the child of the first Tudor king Henry VII and Elizabeth of York was given the name Arthur to recall the Welsh origin of the Tudors and of the legend of King Arthur of the Round Table, and inaugurate a new era in English history. Here is again the power of myth in action, showing a desire to feel connected to our ancestors as ‘a means of forming a sense of identity, or a feeling of “belonging”.’[3] Even if Arthur Tudor died of illness at 16, a new English ‘era’ was indeed initiated by Henry: one separate from the Church of Rome.

Genealogy is not currently taught as an academic discipline, but books like these show how ideas of kingship and authority came to be understood. As such, Eton’s MS 191 has been proposed for inclusion in a large-scale digitisation and research project about genealogical rolls – we hope to be able to reveal more soon…watch this space!

Charlie Barranu, Library Curator

References:

[1] See J. M. Luxford, ‘A Fifteenth-Century Version of Matthew Paris’s Procession with the Relic of The Holy Blood and Evidence for Its Carthusian Context’, Journal of the Warburg and Courtauld Institutes 72 (2009), 87.

[2] Z. Stahuljak, ‘Genealogies’ in E. Emery and R. Utz, eds. Medievalism: Key Critical Terms (Cambridge: Boydell & Brewer, 2014), 75-76.

[3] E. Brand, ‘Why Family History Matters’ in H. Carr and S. Lipscomb, eds. What Is History, Now? How the Past and Present Speak to Each Other (London: Weidenfeld & Nicolson, 2021), 217.