Montem, at one time an initiation ceremony for boys, was a peculiar and spectacular Eton ceremony, was celebrated for centuries until it was abolished in 1844. By the 19th century it had become a grand pageant, in which Etonians processed in elaborate ceremonial and military dress from the College to Salt Hill in Slough. In its final decades Montem was a spectacular, highly attended and widely publicised event. Although many elements of the festival had been altered as Eton adapted to the changing times, much of the traditional Montem remained. Huge crowds flocked to see the procession, glimpse royalty who attended, and participate by giving money in exchange for a pinch of salt and a souvenir card.

Money was collected by boys called Salt Bearers and Runners (or Servitors) who dressed in costumes from different countries and eras. The Runners woke at dawn to travel to outlying districts (Windsor Bridge, Colnbrook, Maidenhead Bridge, Salt Hill, Slough, Datchet Bridge, Iver and Gerrards Cross) to collect money. They would return to Eton to deliver their takings to the Salt-Bearers, who carried them in the procession.

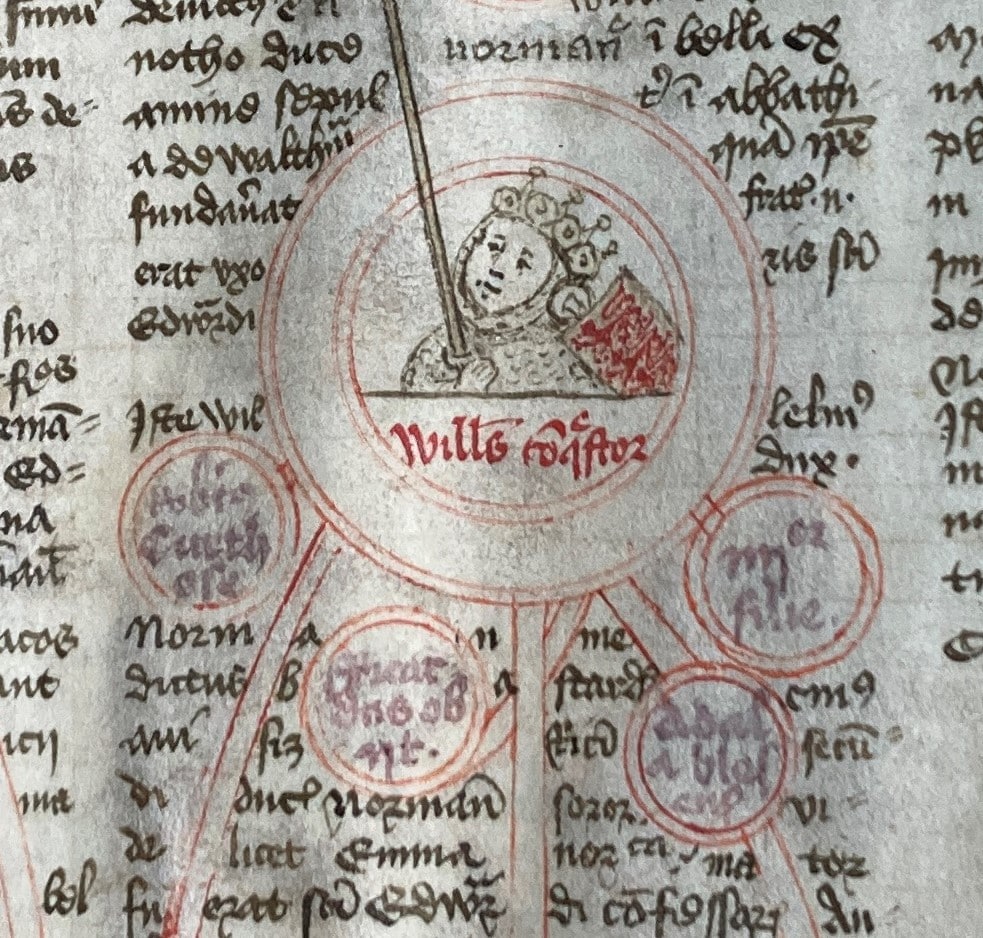

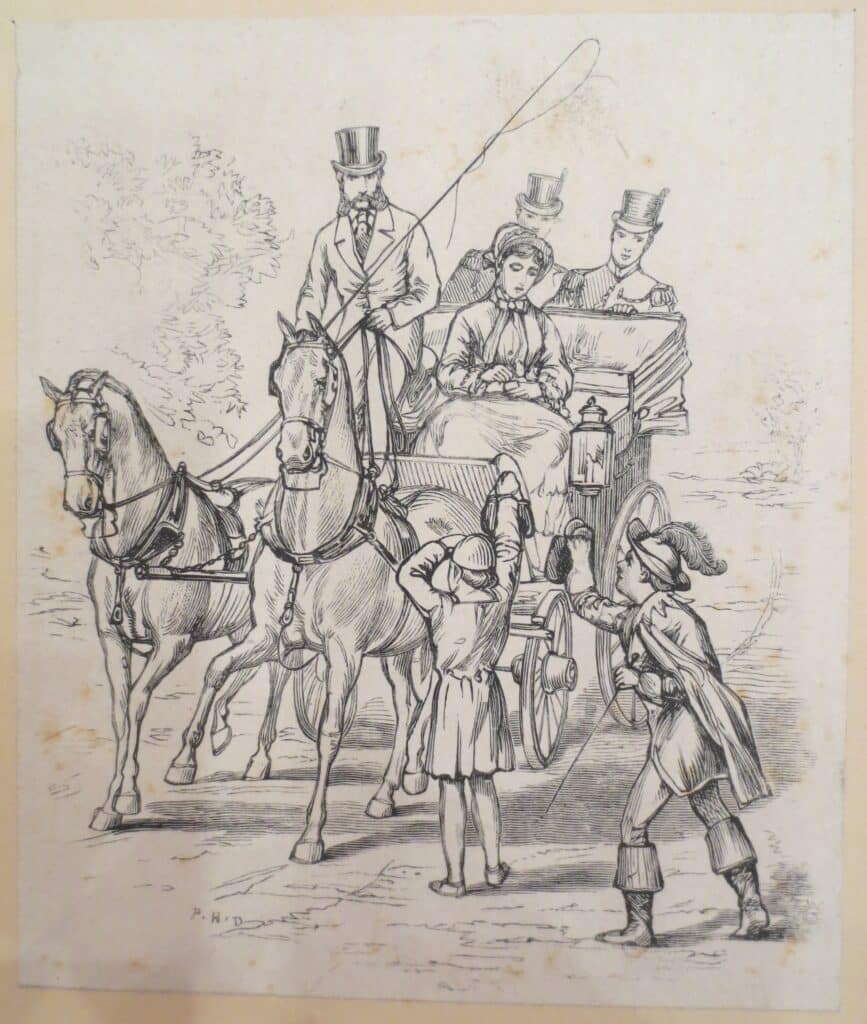

The manner of Etonians stopping passers-by and waylaying carriages to demand payment became a central argument against the continuation of the ceremony. Fundraising by ‘holding up’ members of the public as well as attendees was likened to ‘highwayman’ behaviour. Setting this alongside the boys’ high spirits that often descended into disorder, many felt it cast a bad light on the school and its students. A key issue was that the boys rarely seemed to present the payment for ‘salt’ as an option; rather, it was almost an enforced toll. In the 17th century King William III was infamously stopped in his carriage by Salt Bearers. Luckily he had heard of this custom as part of the Eton Montem and just in time stopped his Dutch Guards who were ready to cut down the supposed highwaymen.

Today it may seem outlandish to compare the behaviour of a group of schoolchildren to the illegal activities of highwaymen. There had been a long history of highway robbery associated in particular with the Bath Road and area of Salt Hill in Slough, the site of Montem Mound which featured as the pinnacle of the procession. In the 17th century the Bath Road became the second stop of the stagecoach route from London to the West, and new inns were built in order to stable the large numbers of horses required after the introduction of daily coach travel. In turn, this drew highwaymen to the area, and the Bath Road was dangerous from London and through Slough. Highwaymen were robbers who targeted the coaches of wealthy travellers and courtiers attending or residing in Windsor. Highway robbery continued, although much reduced, until as late as the early to mid- 19th century, which means it remained in people’s minds during the final years of Montem.

One particular highwayman was renowned for his illegal activity along the Bath Road. Captain ‘Flying’ Hawkes was famous during the reign of King George III, known for dressing in disguise to befriend travellers in order to glean information on suitable targets to rob. He earned the moniker ‘Flying’ due to the speed at which he flitted between sites and his targets. A story goes that he was dressed as a Quaker at an inn at Salt Hill when he witnessed a traveller boasting that highwaymen were no match for him, and would not even get a ‘single sixpence’ off him. Hawkes shortly after robbed him of all his valuables, leaving him with half-a-crown and a warning not to brag in future.[1] Later that very day Hawkes was caught whilst intervening in a fight at an inn in Woolhampton by the Bow Street Runners, the first professional police force who were grouped together to tackle the increasing crime rate. He was later hanged at Tyburn, the gallows that served as the main place of execution in London.

Partly due to such unfortunate associations, the days of the Montem tradition were numbered by the time it had evolved into the lavish but controversial spectacle of the 1840s, and it was abolished by College authorities in 1844.

Ad Montem: Eton’s Lost Procession is open in the Verey Gallery until the 15th October 2023, on Sunday afternoons from 2.30-5pm and by appointment.

Rebecca Tessier, Museum Officer

[1] M. Fraser, The History of Slough, 2nd ed., Slough Corporation, 1980, pp.66-79