Joachim Bouvet’s L’Estat présent de la Chine (1697)

In 1697, the Jesuit Joachim Bouvet returned from Beijing to France bearing a collection of Chinese woodblocks and paintings. He had been sent to China by Louis XIV in 1687, where he worked at the royal palace and was very close to the current emperor of the Qing dynasty, Kangxi.[1] Upon his arrival, Bouvet published an illustrated book entitled L’Estat présent de la Chine, en figures,which included 42 coloured engravings. These plates were created by Pierre Giffart, who produced copies of the original Chinese works. They showcase elegant Chinese figures dressed in traditional and ceremonial clothing. According to Bouvet, they were supposed to instruct viewers ‘at a glance, […] of the state and customs of the most ancient and most flourishing Empire of the East’.[2] Its uniqueness lies within the exceptional attention to detail in the portrayal of Chinese garment in a European book, as well as the effort to render its representation as close to the Chinese original as possible. One copy of this rare book is held in the Eton College Collections.

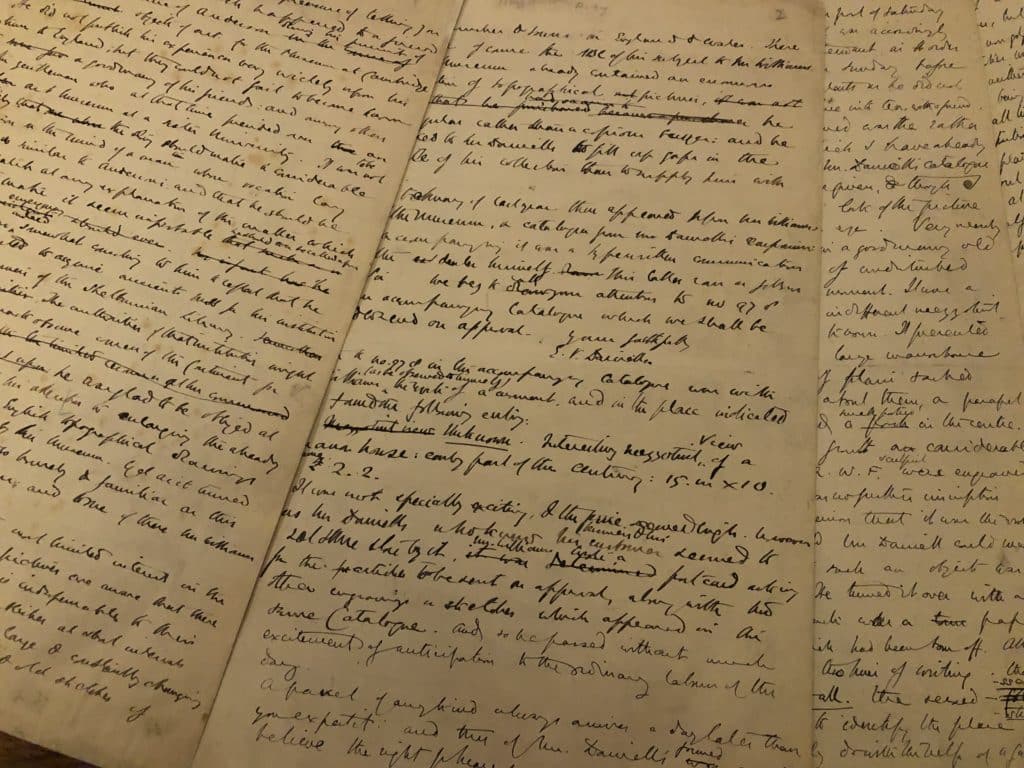

Pierre Giffart, Dame Tartare Mandarine du quatriéme Ordre, in L’Estat Présent de la Chine en Figures, 1697, engraving and watercolour

Giffart and the artists who coloured his engravings in the volume at Eton maintained a high level of accuracy in their renditions of traditional Ming and Qing clothing. For instance, the representation of the red court hats, known as chao guan, corresponds with the formal court attire of princes, noblemen and high officials of the Qing dynasty.[3] Manchu officials and their wives wore square badges entailing animals and mythical creatures that identified their civil or military ranks. All the symbols on the imperial badges on Giffart’s engravings are in accordance with the actual position of their wearer. The large variety of watercolour shades indicates that only the wealthiest of buyers could have afforded this book.

Pierre Giffart, Officier de Guerre Tartare Mandarin du Sixiéme Ordre, in L’Estat Présent de la Chine en Figures, 1697, engraving and watercolour

In L’Estat présent, dress is viewed as an identity marker that categorises human beings. During this period, clothing could communicate the social standing, lifestyle, and character of its wearer, and had moral and political attributes. Thus, dress could reveal essential information about the current state of a country. Printed costume books enjoyed great popularity amongst French readers who were curious about the habits and apparels of both regional and global communities.[4] The richly decorated attires in L’Estat présent conveyed the wealth and sophistication of the Chinese individuals clothed in them. Many attributes that were seen as desirable to a 17th-century French gaze, such as modesty and humility, were contained in this collection of figures. Thus, Giffart’s illustrations were not ‘neutral’ representations of Chinese individuals but were designed to project a highly positive view of the Middle Kingdom.

Beyond merely serving the purpose of enjoyment, Bouvet hoped that this volume would educate readers about the current political landscape in China, and even inspire them to adapt the modesty of Chinese dress. Today, L’Estat présent teaches us about the fascination for China in late-17th-century France, and how early modern European outlooks on the country were generated with the help of imagery that represented traditional costumes.

Miriam Fleck-Vidal, MSt student in History of Art and Visual Culture at Lincoln College, University of Oxford (2021-2022).

[1] Isabelle Landry-Deron, ‘Portraits croisés Kangxi et Louis XIV’, in Kangxi, Empereur de Chine : 1662-1722 : La Cité interdite à Versailles (Paris: Réunion des musées nationaux, 2004), pp. 59-63, p. 59.

[2] Joachim Bouvet, L‘Estat Present de la Chine, en Figures: Dedie a Monseigneur le Duc & à Madame la Duchesse de Bourgogne (Paris: Pierre Giffart, 1697), fol. 12.

[3] Valery M. Garrett, A Collector’s Guide to Chinese Dress Accessories (Singapore: Times Editions, 1994), p. 34.

[4] Ann Rosalind Jones, ‘Habits, Holdings, Heterologies: Populations in Print in a 1562 Costume Book’, Yale French Studies, 119 (2006), 92-212 (p. 92).