The English boarding school experience has been romanticised and popularised since at least the 19th century, and nowhere is this more evident than in Thomas Hugh’s 1857 novel, Tom Brown’s School Days. The protagonist epitomises the cheerful schoolboy character, whose courage and likeable personality enable him to confront and challenge the novel’s antagonist, Flashman. As the story develops, Brown and his friends become model Victorian students who are pious, brave and protectors of the weak.

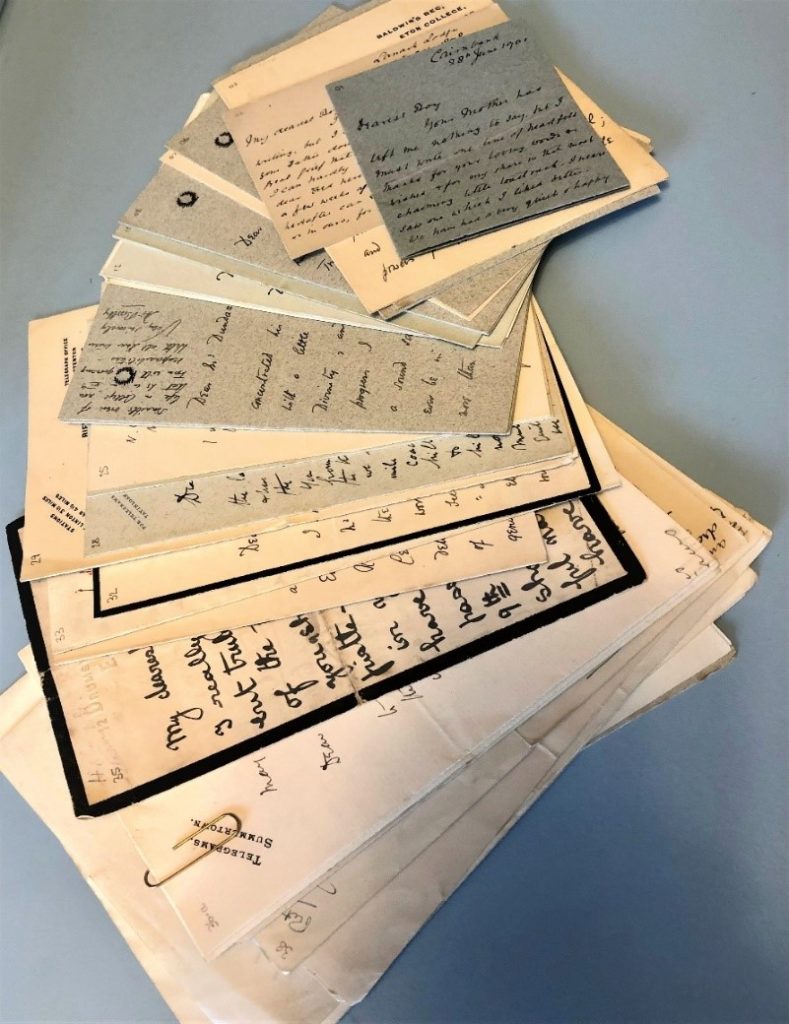

In reality, life at public school was more complex. It included months living away from family, sharing a boarding house with strangers and studying an academically rigorous curriculum. Writer Edward Lucie-Smith, who boarded at The King’s School, Canterbury, once opined ‘that school would be a place of imprisonment and terror. By and large, my sombre expectations were fulfilled’.[1] With this in mind, I have been cataloguing a series of letters (c.1894-1925) pertaining to Old Etonian, Robert Hamilton Dundas.

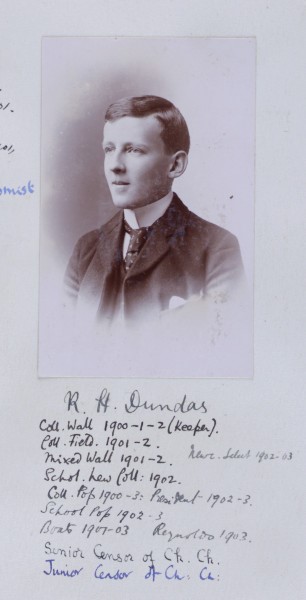

Eton Collections | PA-A.226:529-2015

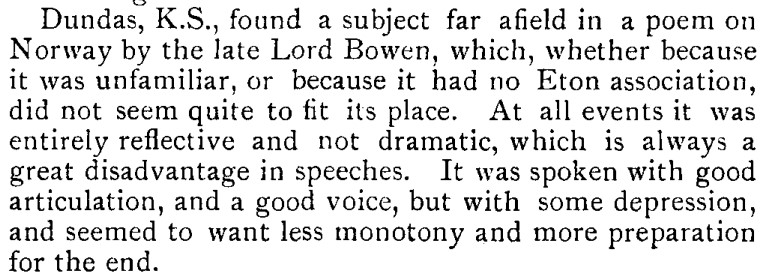

Educated at Summer Fields Preparatory School, Dundas, known affectionately as Robin, attended Eton as a King’s Scholar in the Autumn of 1897. His Prep master, C.E Williams, reported with excitement that ‘this is indeed a triumph for the little lad, his place is higher than I had ventured to hope’.[2] Receiving a King’s Scholarship demonstrated a commitment to learning, and Dundas would have lived alongside 69 other equally intelligent scholars in the Foundation Buildings in the College’s School Yard. While academia was important, much of Dundas’s school-life would have been taken up with sports. Our records reveal that he played College Wall and was Keeper in 1902. While athletic, it was reported that during the 1901 St Andrews Day Oppidans vs Collegers match, Dundas could have been ‘more careful about the direction of his kicks’[3] Additional entries from The Chronicle[4] reveal that he regularly played cricket, football and participated in the Procession of Boats celebrations for the Fourth of June.[5]

At Eton, he received glowing reports for his studies in Divinity and Classics. His Christmas report from 1899 states that he was ‘sent up for good in both Classics and Mathematics’.[6] Dundas also participated in the Newcastle Select, an annual prize at Eton for the highest performance in a series of special examinations; in the Easter of 1901 he came a respectable 13 out of 38. Dundas made an impression on one particular master, H.T. Bowlby, who wrote that ‘in conduct he remains the best of boys’.[7] Similarly, relationships between masters and students could be quite strong, with Bowlby lamenting the loss of Dundas nearing the end of his time at Eton. He informed the boy’s parents that he would help towards his future in any way, and thanked them for sending him ‘such a son’. [8]

Dundas became particularly close to one boy at Eton named J.M. Keynes, whose name appears numerous times in his letters; the latter was also a King’s Scholar from a similar upper middle-class background. During school leave, the two regularly corresponded and updated each other on their holiday antics, with Dundas once cruelly describing his godmother as ‘old, skinny, yellow, marvellously old fashioned, splattered with diamonds and pearls’.[9] When Dundas was accepted into New College, Oxford, Keynes nostalgically remarked that their group of friends ‘were a fine lot of fellows, there is no doubt about it’.[10]

At Oxford, Dundas continued to excel academically and was under the tutorage of Alfred Zimmern, a renowned scholar of classics. Soon after graduating, Dundas was appointed to a lectureship at Liverpool University, not an unexpected achievement given that during his undergraduate degree he was described as a most ‘articulate scholar’.[12] Only a year following this, he undertook a tutorship at Christ Church, Oxford, where he taught Greek history for almost 50 years.[13] As with many old boys, Dundas remained in contact with former Etonians long into adulthood, and regularly corresponded with the aforementioned J.M. Keynes, who would often berate him for not having enough spare time to visit him!

Robert Hamilton Dundas died in 1960, having spent the majority of his life working in education. Evidence from the 1,648 names in his visitors’ book suggest that he remained popular throughout his adult life. Overall, his letters from Eton are a wonderful insight into the lives of public schoolboys in the late 19th and early 20th century, and I have thoroughly enjoyed working on this project.

By Alexander Taylor, Archives Assistant

Footnotes:

[1] Quigly, Isabel. The Heirs of Tom Brown, (1982, Chatto & Windus, London). p.23.

[2] ED 487 01. R.H. Dundas: Correspondence. Letter 36.b, 14 July 1897.

[3]The Chronicle, 30 November 1902

[4] The Chronicle is a student-led newsletter that reports on the general on-goings of the College. This often includes sporting events, society events etc. Attached is a link to the digitised edition of the newsletter.

[5] The Fourth of June is the occasion when Eton College celebrates the birthday of George III, a great supporter of the school, with a grand festival of speeches, cricket and the procession of boats.

[6] ED 487 01. R.H. Dundas: Correspondence. Letter 4, Christmas 1899.

[7] Ibid.

[8] ED 487 01. R.H. Dundas: Correspondence. Letter 34, Election, 1903.

[9] ED 487 01. R.GH Dundas: Correspondence. Letter 29, 7 January 1902.

[10] ED 487 01. R.H. Dundas: Correspondence. Letter 46, 19 December 1906.

[11] Thorpe, D.R. Supermac: The Life of Harold Macmillan (2010 Vintage Publishing).

[12] ED 487 01. R.H. Dundas: Correspondence. Letter 44, 14 July, 1907.

13. Mason, J. Dundas, Robert Hamilton (1884–1960), classical scholar. Oxford Dictionary of National Biography.