The wanderings of Odysseus on his return from the Trojan Wars to Ithaca have served as an archetype for more than two millennia of narratives about travel in western culture. Traditionally ascribed to the blind poet Homer, the Iliad and the Odyssey are the culmination of an oral tradition dating back to the Mycenaean age, handed down and developed for performance by nameless poets over five or more centuries before reaching their present form around 675-725 BCE. The poems were probably put into writing by the mid-6th century BCE, and the earliest surviving manuscripts are papyri from the 3rd century BCE, when Alexandrian scholars produced a relatively stable text which was copied by scribes and spread across the Hellenistic world. About 300 medieval Greek manuscripts of Homer survive from the 9th to 15th centuries, but in western Europe, Homer’s poems were transmitted through Latin abridgements until the revival of Greek learning in the Renaissance, when the influx of Byzantine refugees after the fall of Constantinople in 1453 brought scholars and the writings of Greek authors to the west.

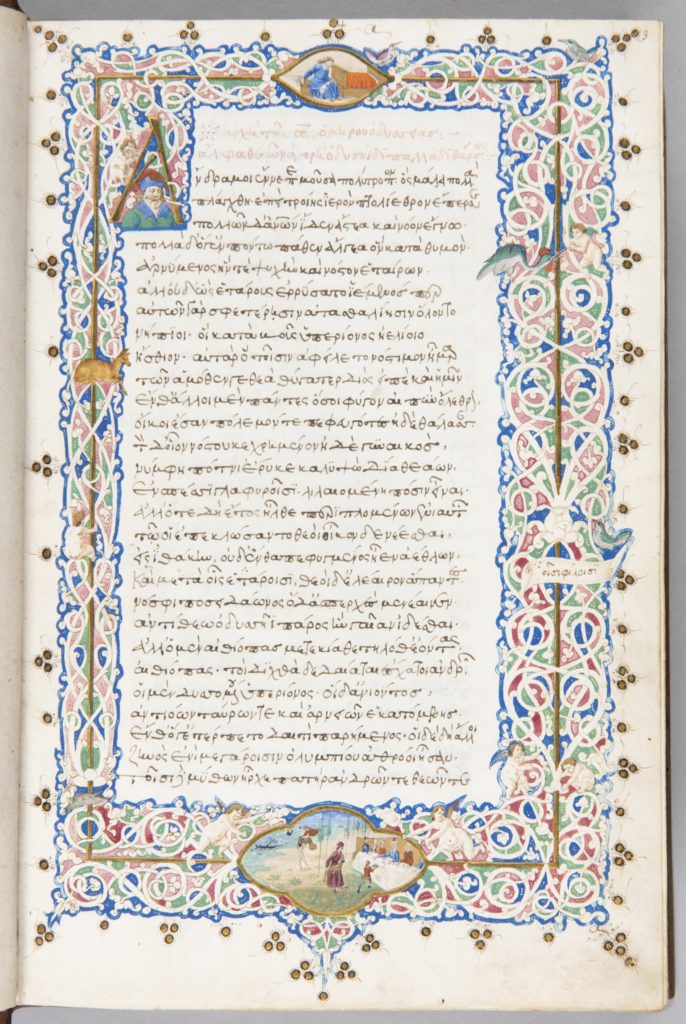

A 15th-century manuscript of the Odyssey in College Library bears witness to this Greek diaspora. Given to Eton in 1954 by the book collector and Old Etonian John Hely-Hutchinson, it is in a binding typical of books from the library of San Marco in Florence, and the scribe has been identified as Joannes Skoutariotes of Thessaly, who was active from 1442 to 1494. Written on fine vellum, the manuscript is mostly undecorated apart from the small illuminated initials and the very fine border of white vines attributed to the miniaturist Filippo de Matteo Torelli, with putti and other creatures peeping out of the vines and vignettes showing scenes from the poem of Penelope weaving and Odysseus coming ashore. A charming feature of the border is the way it incorporates a marginal correction by the scribe, about two thirds of the way down the right-hand margin.

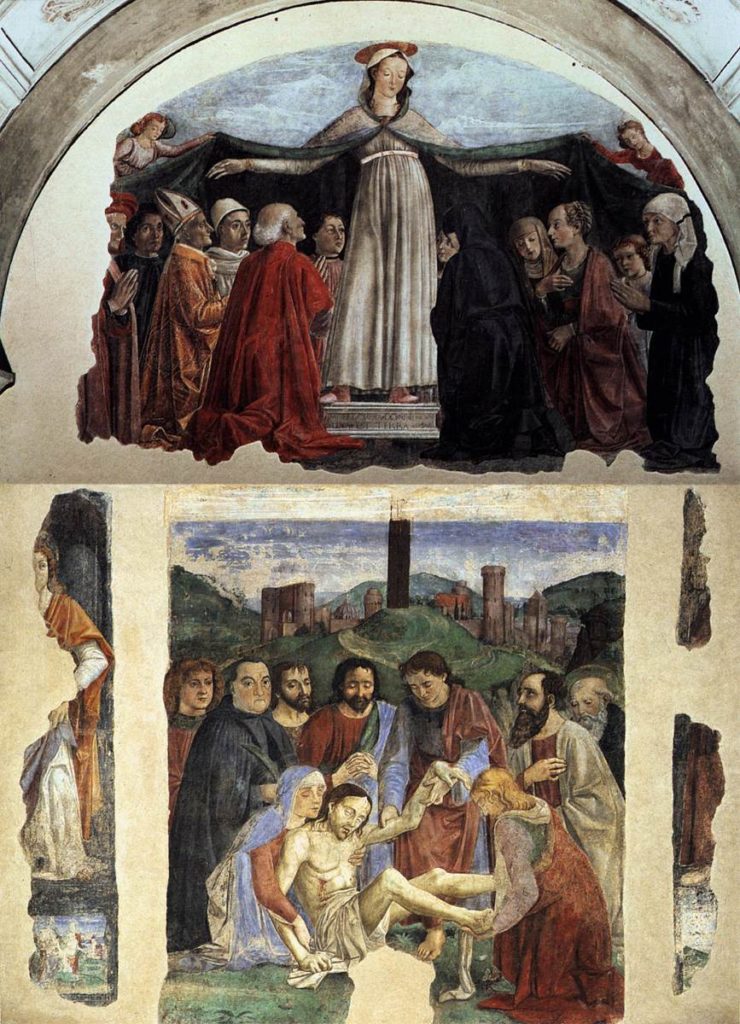

An inscription on the final leaf of the manuscript, erased and barely legible, identifies the owner: ‘Liber Georgii Antonii Vespucci’ [the book of Giorgio Antonio Vespucci]. The youngest of three brothers of the Vespucci family of Florence, Giorgio Antonio Vespucci studied with the notary and humanist scholar Filippo de Ser Ugolino Pieruzzi, who inspired in him an interest in voyages, astronomy and discussions of the shape of the earth. He became a Dominican friar, scribe and teacher of classics in humanist circles, numbering among his friends the Neoplatonist philosopher and astrologer Marsilio Ficino and the Dominican preacher Girolamo Savonarola. In addition to copying books for the family library and for others, Giorgio Antonio Vespucci formed a notable collection of manuscript and printed books in Latin and Greek, estimated at between 150 and 200 volumes, and after his death the majority of these were bequeathed to the Dominican convent of San Marco.

As an educator, Vespucci taught young men from the best families in Florence and foreigners drawn to the city by the lure of humanism, including Greek and Byzantine exiles. Among those to whom he imparted his knowledge was his nephew Amerigo, who was intended for a commercial career which eventually led him to join between two and four voyages of exploration to the Americas in the service of Spain and Portugal around 1500. The exact number is disputed, as is Vespucci’s authorship of letters describing the voyages, which may be fabrications by others based in part on genuine letters. However, the publication and widespread circulation of the letters under a Latinised form of his name, Americus Vespucius, is thought to have inspired the cartographer Martin Waldeseemüller to coin the name ‘America’ in his 1507 world map, the Universalis Cosmographia, the first to show the Americas as a separate continent from Asia.

A composition book from Amerigo’s time at his uncle’s school survives in the Biblioteca Riccardiana in Florence. In it, he set down ideas and discussions on a variety of subjects and translated them into Latin. They travelled together to Rome, and Giorgio Antonio seems to have inspired his nephew with a love of travel and belief in its benefits. One passage reads: ‘Going back and forth to many distant lands, where by talking and trading one can learn many things, not a few merchants have become wise and learned … Moving about and making enquiries concerning the world, whose limits we have not yet completely ascertained, they can furnish valuable advice …’. It is tempting to believe that perhaps Amerigo Vespucci pored over his uncle’s manuscript of the Odyssey, or at least listened to tales from the poem.

By Stephie Coane, Deputy Curator of Modern Collections

Giorgio Antonio Vespucci’s copy of the Odyssey is on display in the current exhibition in College Library’s Tower Gallery, ‘VOYAGES: a journey in books’. The exhibition is open 24 November 2017 – 30 April 2018, Monday to Friday, 9.30-1 and 2-5 by appointment. To book, please contact us at [email protected] or 01753 370590.