The exhibition centres on a Japanese object from the Eton College Collections: a lacquer box containing the Nijūichidaishū (‘Collections of 21 Reigns’). It is an anthology of a type of Japanese poetry called waka, which was commissioned by different Emperors between the 10th and 15th centuries. This copy was donated to the College by the Japanese Crown Prince Hirohito (1901-1989), later Emperor Shōwa, after his visit to Eton in May 1921.The exhibition highlights the Crown Prince’s visit to Eton College as part of his European tour, Japanese courtly culture, and waka, as well as recurring poetic themes such as nature and the seasons.

Originally intended to mark the centenary of the Crown Prince’s visit in 2021, the physical exhibition held at Eton (November 2022 to April 2023) showcased items from the College Collections as well as loans from the British Museum and Ashmolean Museum.

Courtly Culture and Waka Poetry

Nature and Japanese Poetry

The Nijūichidaishū – Japan’s imperial waka poetry anthology

Curated by Dr Monika Hinkel (SOAS, University of London)

The curator is very grateful to the Eton team: Lucy Cordingley, Catrina Brizzi, Dr Carlotta Barranu, Claude Grewal-Sultze, Sara Spillett, Bryan Lewis.

Our sincere thanks to the individuals and institutions whose assistance has made this exhibition possible: Sir David Verey, The British Museum and The Ashmolean Museum and the Ezen Foundation.

For further support and assistance, thanks to Jason James, Michael Spencer, Dr Thomas McAuley, Edmund Ryan, Damian Stanford-Harris and the C Block Japanese language students, Nao Fukui (IRS), Alexander Hogevold (JNO) and Ilya Kimura Avakiants (HWTA).

Design by Ann-Louise Schweizer

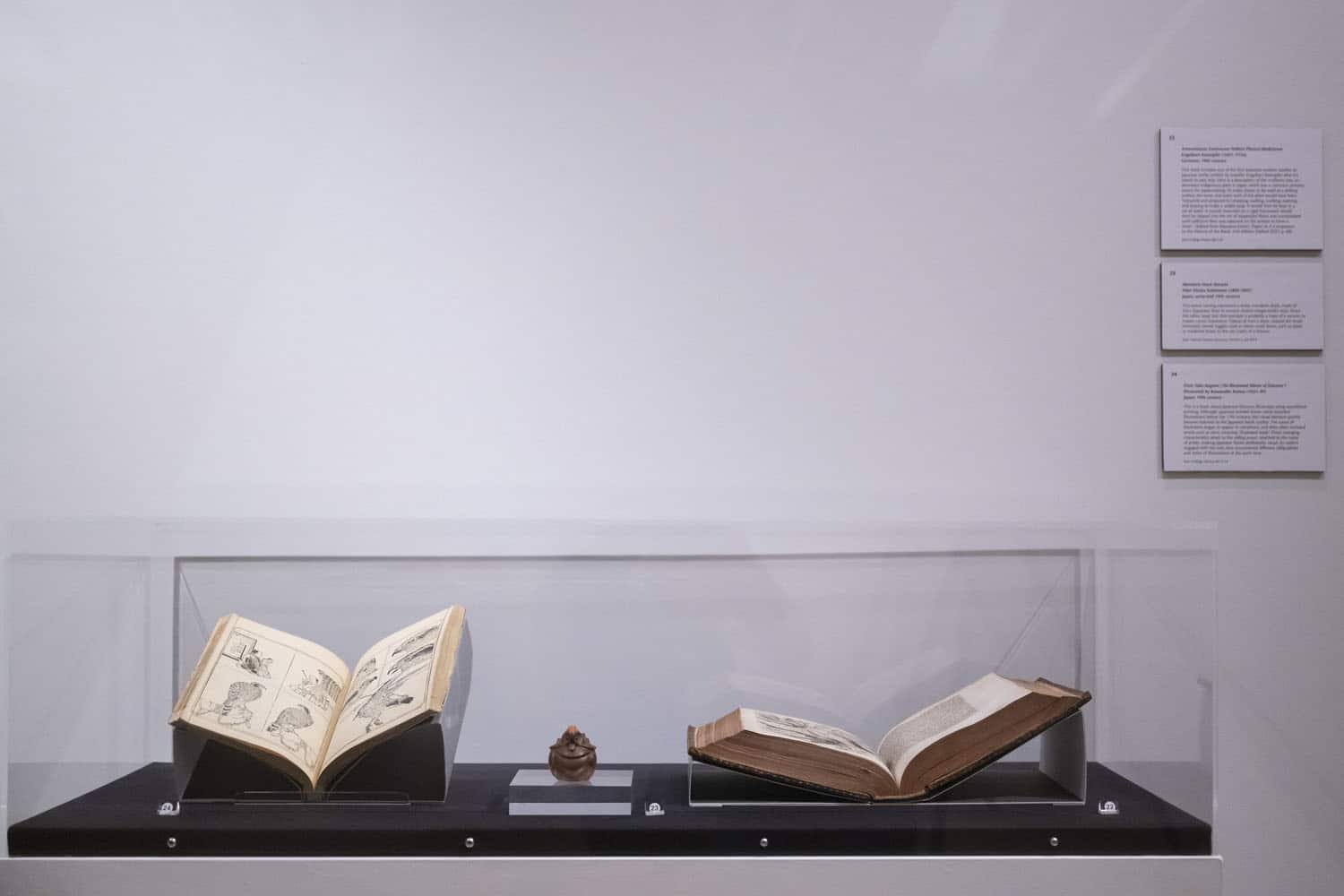

Mandarin Duck Netsuke, after Hirata Suketomo (1809-1847), Japan, early-mid 19th century

Eton Natural History Museum, NHM-CL.38-2015

Ehon Taka Kagami (‘An Illustrated Mirror of Falconry’), illustrated by Kawanabe Kyōsai (1831–89), Japan, 19th century

Eton College Library, Id7.3.14

Amoenitatum Exoticarum Politico-Physico-Medicarum, Engelbert Kaempfer (1651–1716) Germany, 18th century

Eton College Library, Bg.5.29

Nature and Japanese Poetry

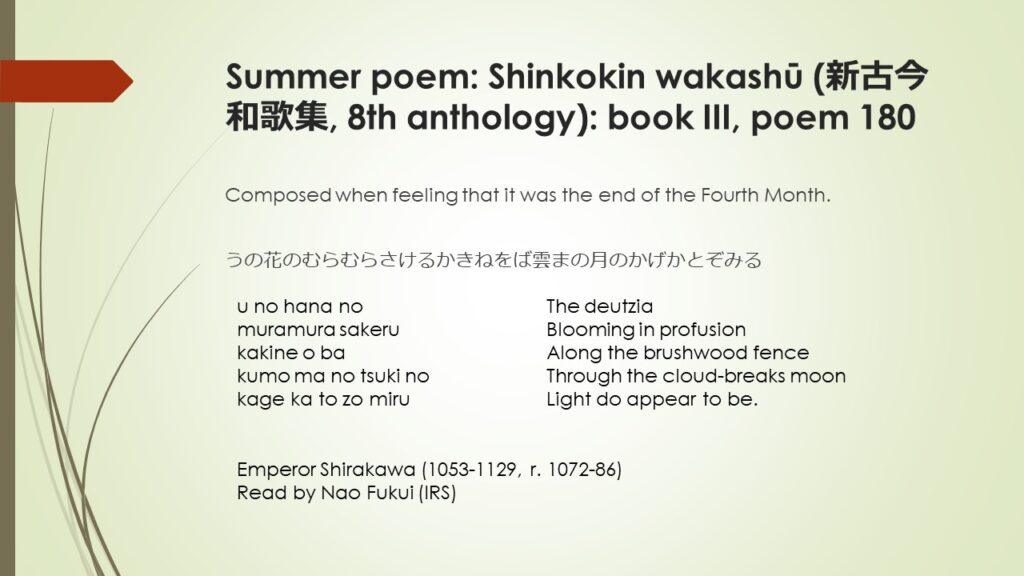

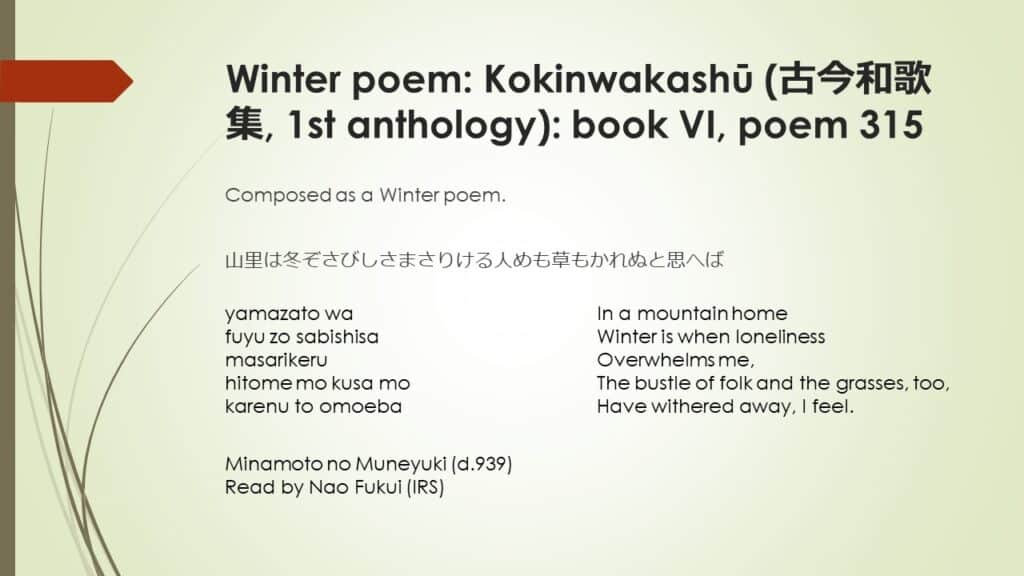

Waka often relate to the four seasons and nature. In the preface of the Kokinshū, the poet stresses the importance of the seasons and nature in Japanese poetry:

“Hearing the warbler sing among the blossoms and the frog in his fresh waters — is there any living being not given to song!”

To this day, the Japanese celebrate the beauty of the seasons and the poignancy of their evanescence through festivals and rituals every year. This sensitivity to seasonal change is an important part of Shinto, Japan’s native belief system, which focuses on natural cycles of life, death, and renewal. Similarly, waka celebrate the sensual appeal of elements of the natural world, imbuing the seasons with human emotions. Furthermore, poems are expressed visually through elegant calligraphies, imaginary portraits of poets and depictions of nature. These works also convey an artist’s respect for the great poets of the past and the desire to emulate their accomplishments. High-ranking members of court society would copy poems on elegantly decorated papers, transforming manuscripts into luxury objects.

Silver Cigarette Box, Japan, 20th century

The box may have been gifted by Crown Prince Hirohito to Provost M.R. James.

Eton College Fine & Decorative Art, ECS-S.143-2015

Letter from the Imperial Household, Japan, 1925

Eton College Archives, COLL LIB 22 10

Imperial Award Honouring Frank Ashton-Gwatkin, Japan, 1921

Eton College Library, MS 677/03/06

Courtly Culture and Waka Poetry

The term waka (和歌, ‘Japanese verse’) generally refers to classical Japanese poetry. The term was coined during the Heian period (794 – 1185) to differentiate native poetry from kanshi, the Chinese poems with which educated Japanese would have been familiar. Waka has its origin in folk songs, and it became an important art form at the Japanese imperial court as early as the mid-8th century. Waka consist of 31 syllables, with verses arranged in five lines in an alternating pattern of 5-7-5-7-7 syllables. The term is occasionally also used as a synonym for tanka (‘short poem’), the basic form of Japanese poetry. It is mainly written in kana (phonetic syllable alphabet), interspersed with Chinese characters (kanji). The poems are written in flowing form, showing characters and syllables in a fast and abbreviated manner. The oldest extant waka dates to the early 8th century.

Poetry was an important means of communication at the imperial court, enabling the members of the nobility to converse in a refined and indirect way. A person’s skill in poetry was a major criterion in determining their standing in society, as waka became used in social circles including warriors, priests, and the rural elite. Reciting waka was therefore not just a cultural accomplishment but a profession, ranking alongside Chinese poetry and ancient court music. The families that took it on passed down this art form from one generation to the next.

Many rituals and events surrounded the composition, presentation, and judgement of waka. For instance, there were two types of waka parties: utakai and utaawase. At utakai, all participants wrote waka verses and recited them, while at utaawase two teams would compete against each other. The first recorded utaawase was held in around 885 and, at first, it was simply a playful form of entertainment. As the poetic tradition deepened and developed, it turned into a serious aesthetic contest, with considerable formality. The winning poems from the competitions were preserved in imperial poetry anthologies. Today, the imperial family still holds utakai: the one held on New Year’s Day was established by Emperor Kameyama in 1267. The emperor himself releases his own poem for the public to read and announces a theme for an annual waka writing contest that is open to all.

In the eleventh century, Fujiwara Kintō (996-1075), a Japanese nobleman, scholar, and poet, selected thirty-six waka by celebrated authors of the past. They would be known as the Sanjūrokkasen, or Thirty-six Immortal Poets. In the early 13th century, retired Emperor Gotoba (1180-1239) designated another group of poets, one hundred in all, as Immortal Poets. Throughout the medieval and pre-modern times, paintings and prints featuring depictions of the immortal poets were created and cherished. Combinations of poet portraits and representative poems (kasen-e), emerged in the 13th century, produced on horizontal scrolls representing the poets in competition (utaawase).

During the Heian period, before the birth of kimono, a beautiful garment culture blossomed. By the 11th century the Chinese-style costumes (karafu) that had been prevalent earlier in the imperial court evolved into uniquely Japanese garments, such as the women’s layered jūnihitoe, and inner pleated trousers (keiko). Even among the wide variety of traditional robes, these stood out for the quality of their silks, their combinations and layering of colours, and their voluminous, sumptuous fabrics. The colours and colour co-ordinations created by the layering of garments had poetic names evocative of the seasons.

The arrangement of these colours was important for conveying a sense of refinement and good taste. Too pale or too bright colours could become a point of criticism or wearing colours that clashed or were inappropriate for the season could ruin a person’s reputation.

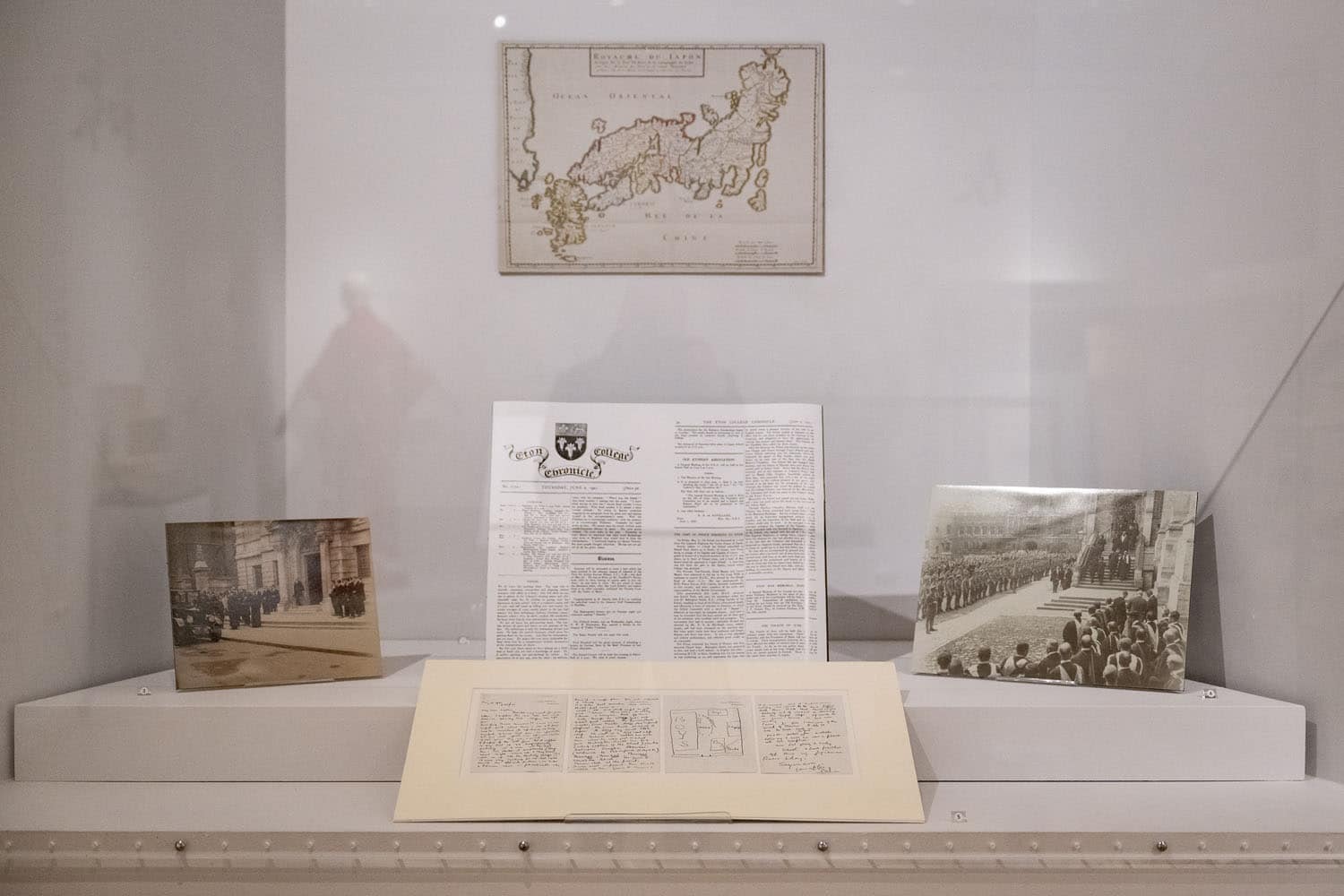

Letter from Patrick Halsey describing the visit, 1921

Eton College Archives, ED 11 05

VISIT OF CROWN PRINCE OF JAPAN

Eton Photographic Archive, PA-A.161:20-2014

Arrival of Crown Prince Hirohito outside School Hall

Eton Photographic Archive, PA-A.6:19-2012

The Eton College Chronicle

Eton College Archives, SCH P 17

Map of Japan, Philippe Briet (1601-1688) France, 17th century

Eton College Library, Se.2.03, map no. 64

Crown Prince Hirohito’s visit to Eton College

On 3 March 1921, Crown Prince Hirohito embarked on a six-month tour of Europe, the first time a member of the Japanese royal family had left the country. He celebrated his 21st birthday on board near Gibraltar and disembarked at Portsmouth on 9 May 1921, accompanied by his uncle Prince Kanin and Count Chinda Sutemi, his political adviser. He was welcomed by King George V at Victoria Station and was then occupied with formal visits, sightseeing, and banquets in both England and Scotland, visiting Windsor, Manchester, Oxford, Cambridge, and Edinburgh, amongst other places.

On 27 May 1921, Crown Prince Hirohito visited Eton College as a part of his tour. He was greeted by an assembly of pupils and teachers shouting ‘Banzai!’, a Japanese greeting meaning ‘ten thousand years of long life’. When he was shown the College Library, the librarian lamented the lack of Japanese books, which Hirohito promised to remedy. The prince later recalled ‘pleasant memories’ of his visit to Eton.

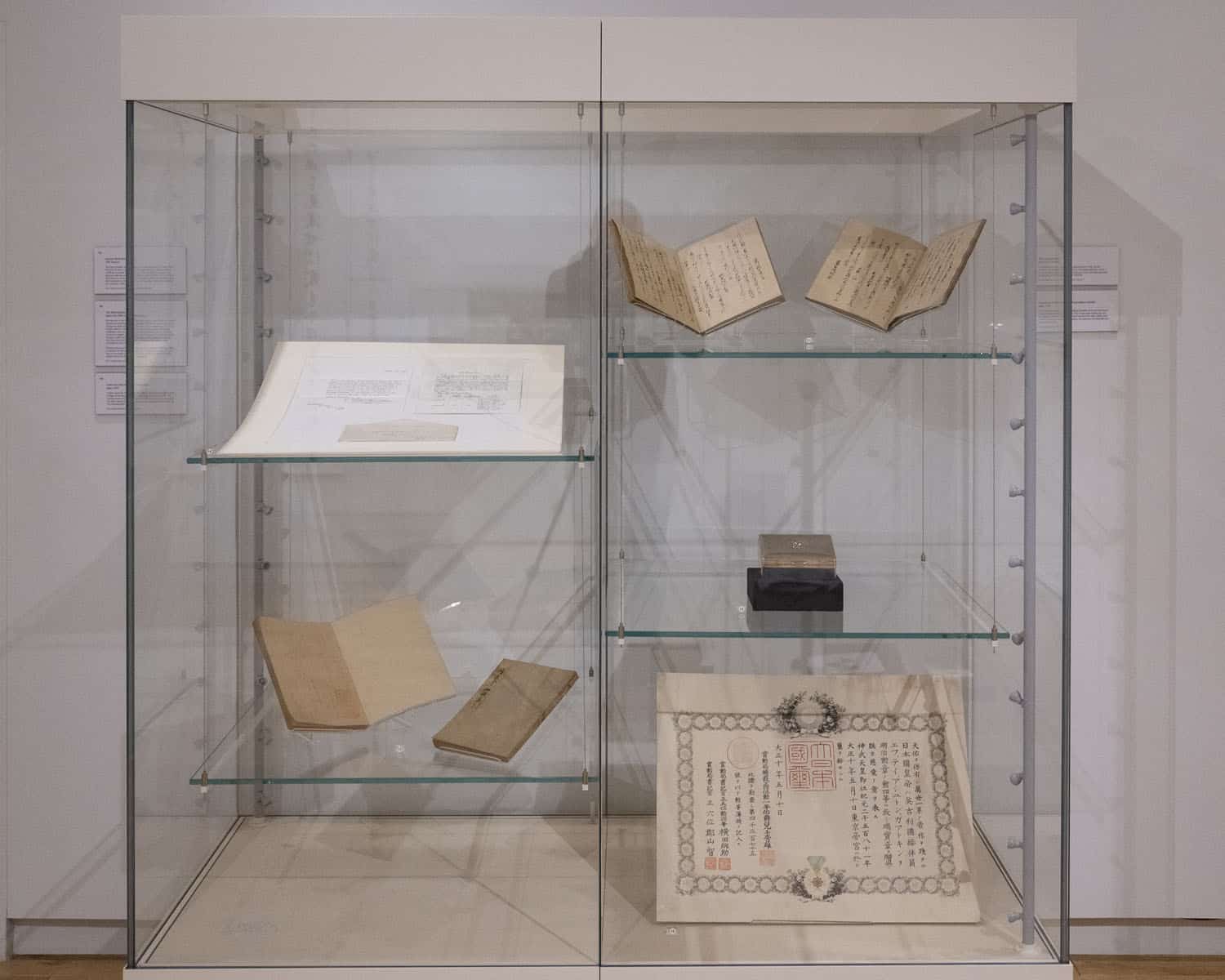

The Nijūichidaishū, Japan, late 19th-early 20th century

Eton College Library, MS 236

Lacquer Wood Box, Japan 19th Century

Eton College Fine & Decorative Art, FDA-A.304-2013

The Nijūichidaishū

Crown Prince Hirohito kept his promise to support Eton College Library, and in August 1925 he gifted Eton a lacquer box containing handwritten books of the Nijūichidaishū, an anthology of waka compiled by imperial command. This copy was created sometime between the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Thanks to its commission, the anthology had an important socio-political function: to demonstrate the prestige of the emperor, while affirming the social order propagated by his rule.

The Nijūichidaishū contains 21 distinct compilations, totalling more than 33,000 individual waka.

The Kokinshū, the first compilation, and one highlighted in the exhibition, engages with two main topics: the seasons and love. The poems progress through the sequence of seasons, and similarly, the love poems are ordered according to the presumed process of a courtly love affair. The compilers of the anthology often added a headnote identifying the author, specifying the topic, and describing the circumstances that prompted the poem. The Kokinshū includes poems from 130 named poets, while around 450 poems are recorded as anonymous. The poetry in the Kokinshū uses refined and elegant language, which is often witty through intricate wordplay and literary puns. Thanks to its diction and intertextual poetics, the Kokinshū served as a model for all later imperially commissioned anthologies: it was considered the apex of the poetic canon, becoming the major source of inspiration for later poets. Commentaries and rituals connected to the Kokinshū therefore developed and were passed down to later generations of poets.

Scrapbook compiled by Frank Ashton-Gwatkin (1889—1976)

England 1921

Eton College Library, MS 677/03/06

Photograph of Frank Ashton-Gwatkin, Japan, 1913

Eton College Library, MS 677/04/01/05

Prince Regent Hirohito’s Tour of Europe

In 1921, Prince Regent Hirohito took a six-month tour of Europe, including the United Kingdom, France, Italy, Vatican City, the Netherlands, and Belgium.

3 March 1921 Crown Prince Hirohito and his thirty-four-man entourage led by Prince Kan’in, Count Chinda Sutemi, and Lt. Gen. Nara Takeji, entrained at Tokyo Station for the port of Yokohama, from there they were taken by boat to the newly fitted warship Katori

On route to England the Crown Prince visited Hong Kong, Singapore, Columbo/Ceylon (now Sri Lanka), Port Said, Cairo, Malta, and Gibraltar.

His itinerary called for him to stay 24 days in England, 26 days in France, five days each in Belgium and the Netherlands, and eight days in Italy.

7 May arrival at Portsmouth, England, where he was met by Crown Prince Albert of England

King George V and the Duke of Connaught meet him at Victoria station

3-night-stay at Buckingham Palace as a guest of the monarch

Speeches at London’s Guildhall and Mansion House, visits to numerous military facilities, visits to both houses of Parliament, laid a wreath at the cenotaph, visit to Westminster Abbey and the grave of the unknown warrior

13 May 1921 reception at Chesterfield House, Mayfair, London with members of the Japan Society, visit to the British Museum, Bank of England, and the Tower of London

Visits Windsor with the Prince of Wales

Visit to the National Gallery, London

14 May 1921 Oxford as guest of the vice Chancellor, went to several colleges, in the afternoon to the River Thames at Exeter College for summer eight-oar races

London, Daly’s Theatre, play ‘Sybil’ With the Duke of York (later George VI) watches flying and bombing display at Kenley Aerodrome

15 May 1921 visit and lunch at Chequers as guest of Prime Minister Mr Lloyd George

20 May 1921 Scotland, Edinburgh, stayed in the King’s apartments at Holyrood Palace, visited Royal Mile from Holyrood to the Castle, St Giles Cathedral, Thistle Chapel, Parliament House, Royal Infirmary, Reford Barracks

21 May 1921 Blair Atholl, Perthshire Highlands as guest of Duke of Atholl

24 May 1921 Manchester visiting the Royal Exchange, Metropolitan-Vickers works, Crossley Motors Limited

25 May 1921 Manchester Docks and Ship Canal

27 May 1921 visited Eton College

19 July boarded the Katori in Naples

3 September 1921 arrived back in Yokohama

Dai Nihon Bussan Zue (‘Pictorial Record of Products from Greater Japan’) Illustrated by Ando Tokubei (Utagawa Hiroshige III, 1842-94) Japan, 19th century

This is a series of colour prints showing various products of Japan as well as the activities of craftsmen and fishermen. This sheet has been folded onto itself – a format now referred to as concertina, which originated and was primarily used in China. Japanese books produced in such a way were called orihon, which were printed throughout the 19th century and usually contained Buddhist texts.

Eton College Library, Idd8.3.01–Idd8.3.02

The catalogue for the exhibition held at Eton from 24 November 2022 to 16 April 2023 may be viewed or downloaded below.

Selected poetry read by the C Block Japanese language students.