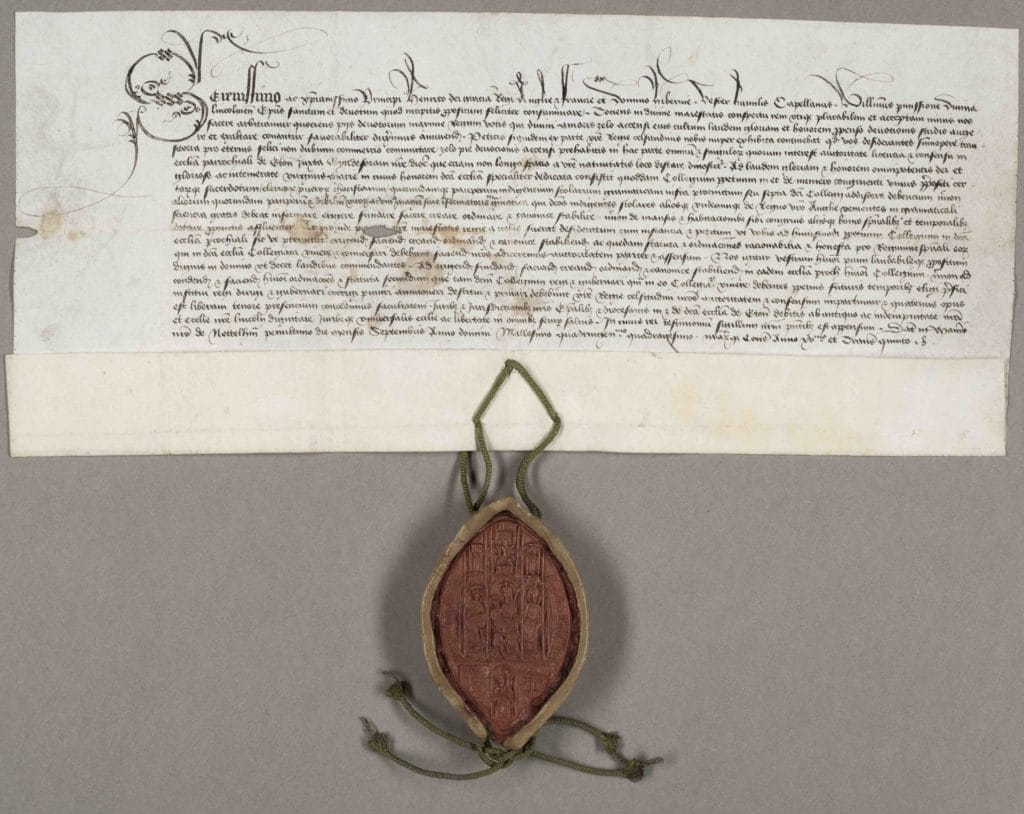

Central to Henry VI’s plans for Eton College was College Chapel, and arrangements for the necessary alterations to the existing parochial church were the first step in realising them. Negotiations were undertaken with the Bishop of Lincoln, in whose diocese Eton lay, to convert the parish church into a collegiate church, dedicated to the Virgin Mary.

The religious aspects of the king’s new foundation were then meticulously laid out, ensuring that services would be conducted on a magnificent scale. Fourteen services a day, plus additional prayers, were to be held by ten priest Fellows, ten chaplains, ten clerks and 16 choristers, all in a church intended to become one of the great places of pilgrimage in Europe.

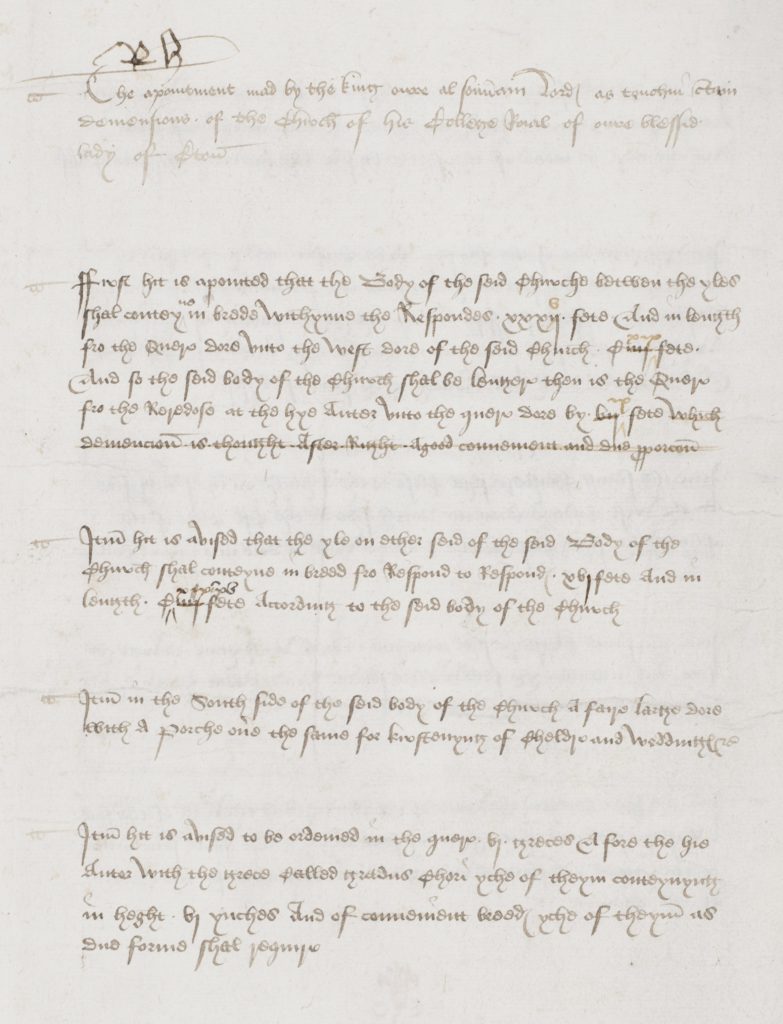

Henry VI left several detailed instructions for the design of the chapel, each version increasing in ambition in order to ensure the chapel would be one of the finest specimens of ecclesiastical architecture in England [ECR 39/75]. Only York Cathedral and St Paul’s Cathedral are wider than the chapel envisioned, with Lincoln Cathedral of similar length. The foundation stone was laid by Henry VI before Passion Sunday, 1441.

A place of pilgrimage

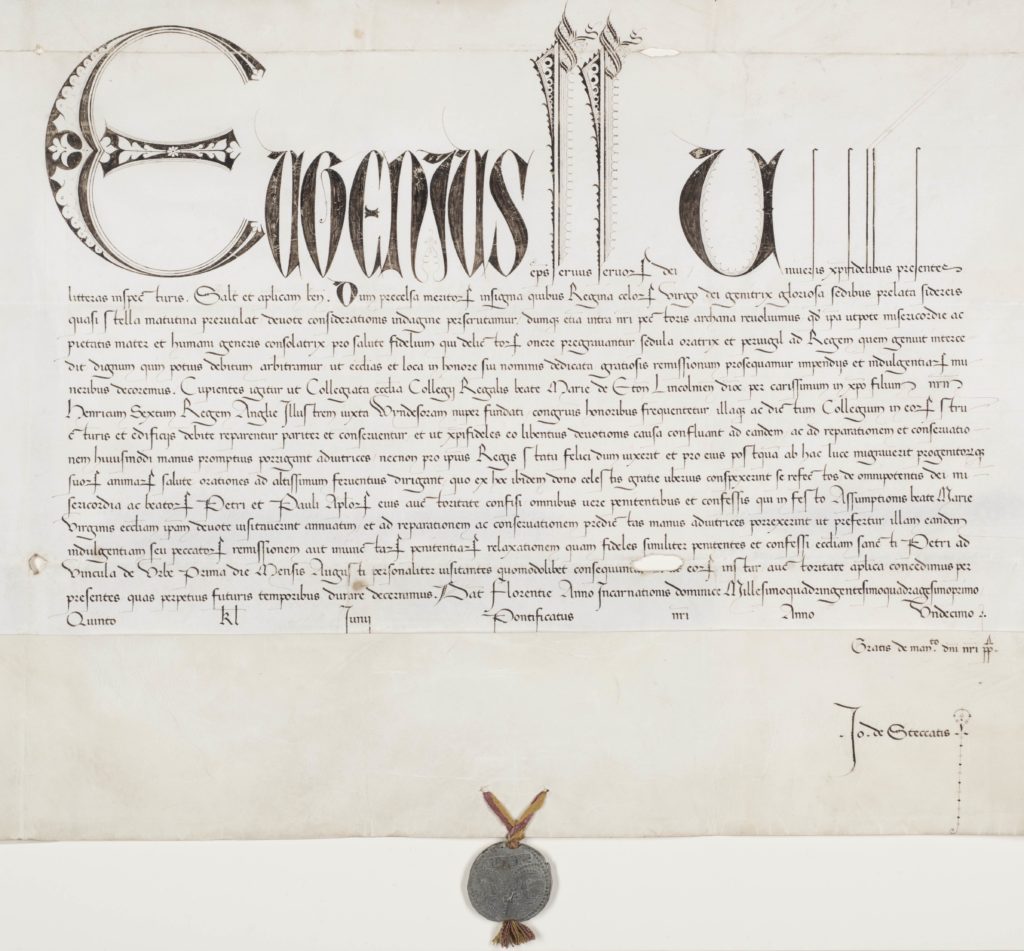

College Chapel was to be a place of great importance, not just for the college but for the country as a whole. To that end, he granted a vast amount of land and a number of privileges and rights, some not held by anywhere else in England, such as the right to grant indulgences.

Worshippers who came to Eton on the feast of the Assumption and contributed to its reparation would be granted time off their stay in Purgatory. In addition, Henry gave Eton a large collection of holy relics, intending College Chapel to become a place of pilgrimage. Inventories drawn up over the years describe these relics and the amazing mounts created for them.

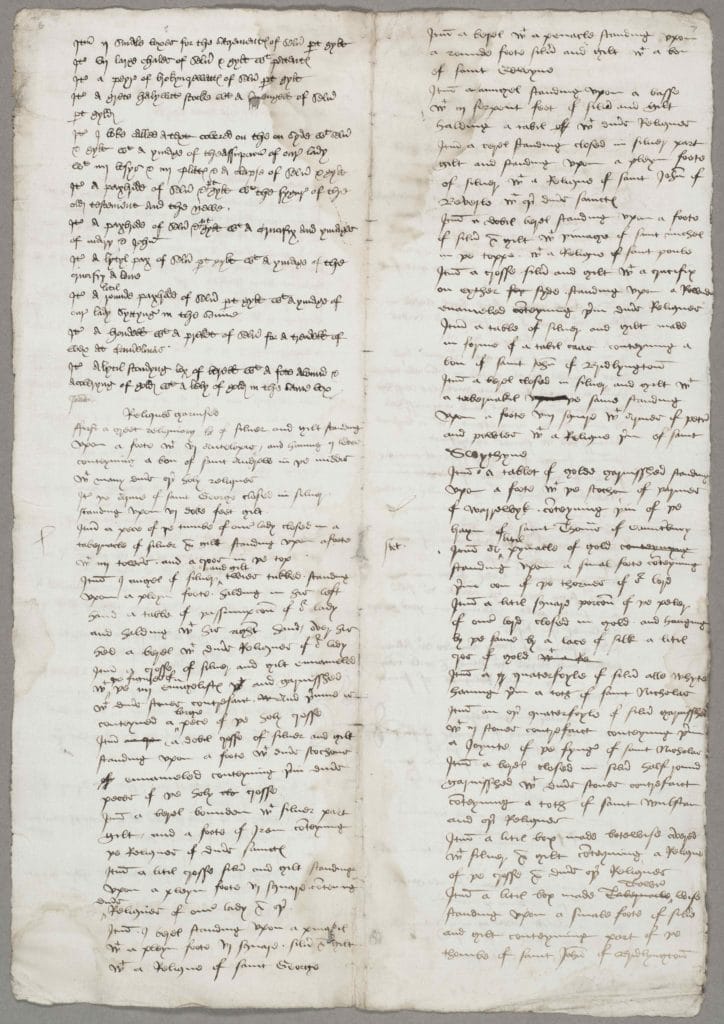

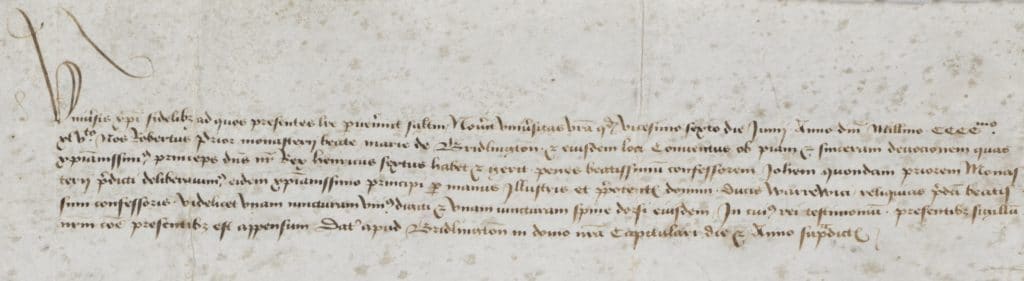

This indenture of goods (left) that were delivered to St George’s Chapel, Windsor, from Eton College in 1465, shows that a large number of holy relics were originally at Eton, given by Henry VI [COLL PF 8/5].

In addition to the ubiquitous Thorn and piece of the True Cross, there were some more unusual items. One of the first items to be gifted by Henry was a piece of the finger and spine of St John of Bridlington.

Born in 1320 in Yorkshire, St John was remembered for the integrity of his life, his scholarship, and his quiet generosity. Recognised as a saint by the Pope in 1401, he would be the last English saint to be canonised before the Reformation. After his death, tales of miracles attributed to him spread throughout the country. Henry V attributed his victory at Agincourt to the intercession of St John of Bridlington and made a number of pilgrimages to the priory. He was therefore a popular saint for the Lancastrians and an eminently suitable one for Henry VI’s enterprise.

Henry VI took possession of the relics on 26 June 1445 and gifted them to Eton. An elaborate reliquary of silver and gilt was built to house them.

of a joint of the finger and a joint of the spine of the blessed confessor John, Prior of Bridlington, 26 June 1445 [ECR 39 45]