Some of the Romantics of the end of Gray’s century dismissed him as part of the poetic establishment. William Wordsworth was critical of Gray the neoclassicist, laying part of the blame at Eton’s door. Overshadowed by the new generation of Romantic poets, Gray’s role as a predecessor was overlooked.

Gray failed as a poet, not because he took too much pains, and so extinguished his animation; but because he had little of that fiery quality to begin with; and his pains were of the wrong sort. He wrote English verses, as he and other Eton schoolboys wrote Latin; filching a phrase now from one author, and now from another.

William Wordsworth to Robert Pearse Gillies, 15 April 1816

It is ironic that one of Gray’s legacies to the Romantics was to revive the figure of the bard, a poet-prophet for the age. Into the 19th century the Romantics continued to cry out for that poet, some of them throwing their own hats into the ring. Perhaps, had he been born a little later or lived a little longer, that bard might have been Gray.

Benjamin Van der Gucht (1753-1794), Thomas Gray (1716-1771), oil on canvas [ECL FDA-P.575-2018]

Ancient Bards

Gray the academic was drawn to the epic medieval poetry of Britain. He returned, too, to the Arthurian legends that had pervaded early British literature, and which would find popularity again with the Romantic poets of the 19th century.

But it was the revival of the figure of the bard that had the greatest impact on the Romantic identity. The ancient Celtic term, adopted by some of the later Latin poets, had once signified a respected storyteller who preserved cultural memory, but in English had come to mean a poet of any kind. In 1760 James Macpherson wrote the first of his popular works of Ossian poetry, which purported to be new translations of ancient Gaelic legends attributed to the Scottish bard ‘Ossian’. But before Macpherson created his bard, and long before Blake and Coleridge evoked their own, Gray described a poet-prophet, separated from the establishment and drawing on their sensibility to speak historic and prophetic truths. Much like the rustic inhabitants of the Elegy, this poet was untainted by the constraints of society and fashionable poetry. This ideal shaped the lives and works of many of the Romantic poets, who sought solitude and freedom in the wild and rustic parts of Britain.

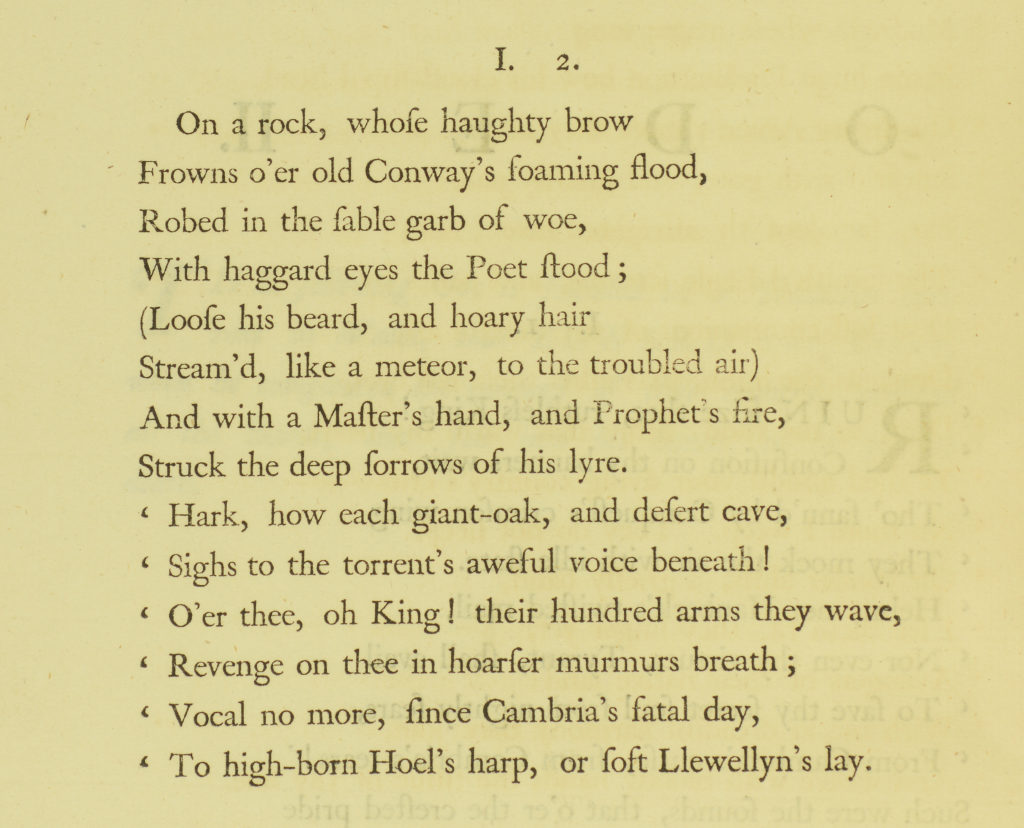

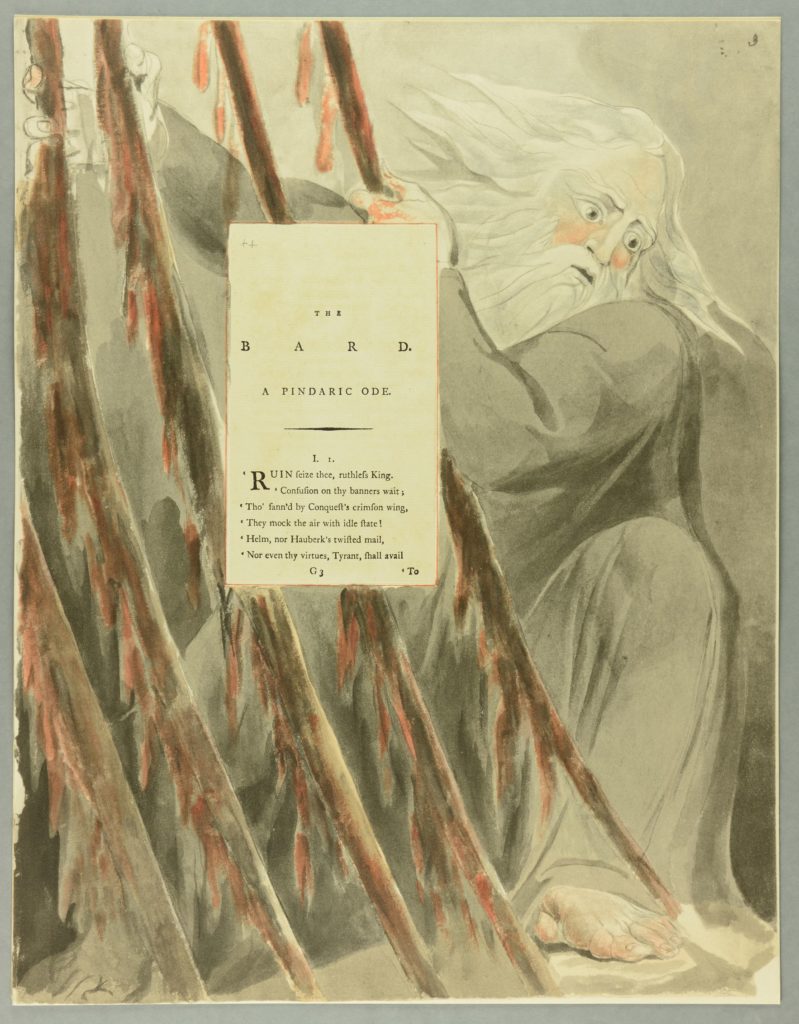

Thomas Gray, ‘The Bard: a Pindaric ode’

Thomas Gray, ‘The Bard: a Pindaric ode’ in Odes by Mr Gray, Strawberry Hill: R. & J. Dodsley, 1757 [Iaa2.5.27]

In ‘The Bard’, Gray takes the Pindaric ode – a poetic form inspired by the lyric poetry of Pindar, writing in sixth century Greece – and applies it to an ancient Welsh narrative that evokes the chivalric epics of the middle ages.

By nature loose in form, the Pindaric ode was applied to grand events or panegyrics on national leaders. Here Gray boldly inverts the form, casting the doomed Bard, not the invading English king, in the heroic role. Truth personified was a familiar feature of neoclassicism, but ‘The Bard’ shows the glory of the outsider speaking truth to power.

‘I felt myself the Bard’, Gray wrote.

With haggard eyes the poet stood;

(Loose his beard, and hoary hair

Stream’d, like a meteor, to the troubled air)

Thomas Gray, ‘The Bard: A Pindaric Ode’ (1757)

William Blake’s illustration of ‘The Bard’

William Blake, ‘The Bard: a Pindaric ode’ in William Blake’s water-colour designs for the poems of Mr Gray, London: Trianon Press, 1972 [Lt.1.09] Reproduced with the kind permission of the University of California

‘Hear the voice of the Bard!’ writes William Blake in the opening line of his introduction to Songs of Experience, published in 1794. By 1797 Blake was working on his Illustrations to Gray’s Poems, surrounding the leaves of the 1790 edition of Gray’s works with his own vivid, often literal and highly Romantic illustrations. Here the Bard is a wild inversion of Urizen, the embodiment of tyrannical enlightenment in Blake’s own mythologies.

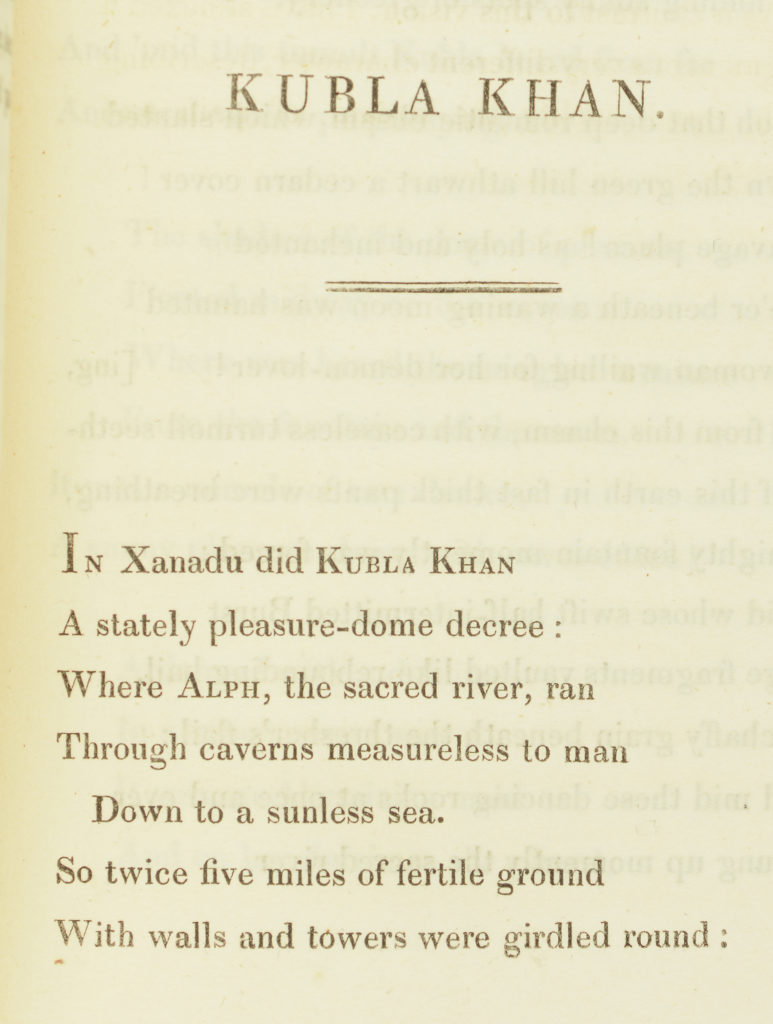

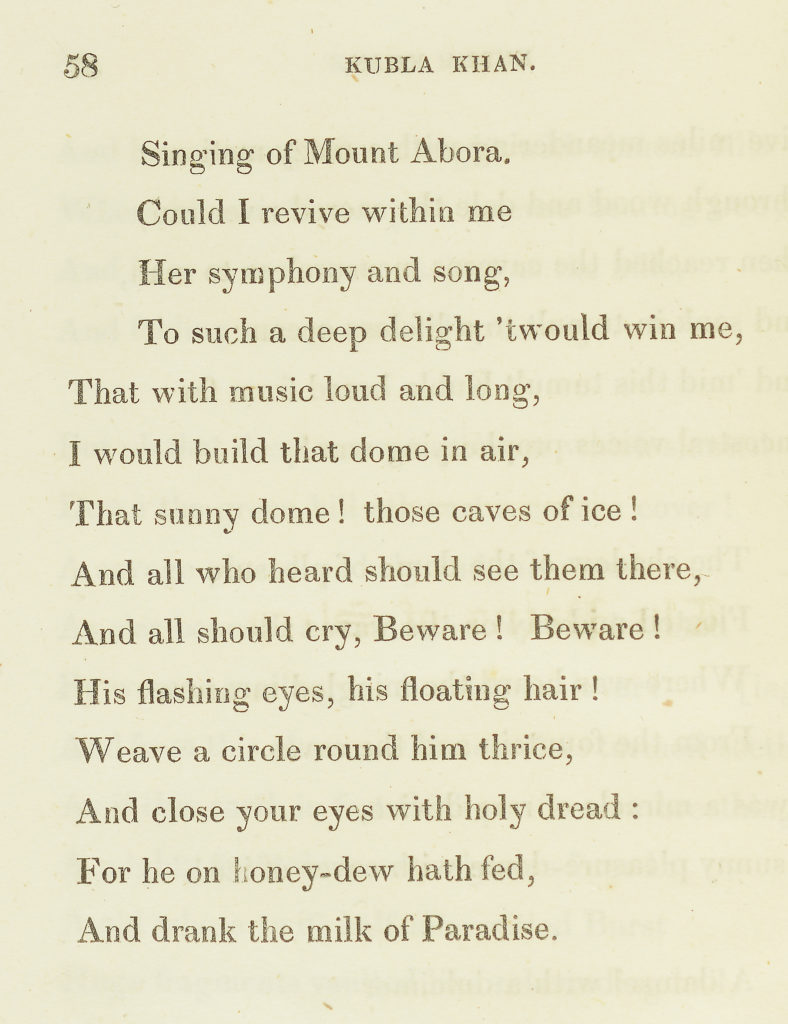

Samuel Taylor Coleridge, ‘Kubla Khan’

Gray’s Bard is recreated most evocatively in Samuel Taylor Coleridge’s ‘Kubla Khan’, where the narrator imagines his own transformation into the bard-poet figure, made fearsome by his creative power.

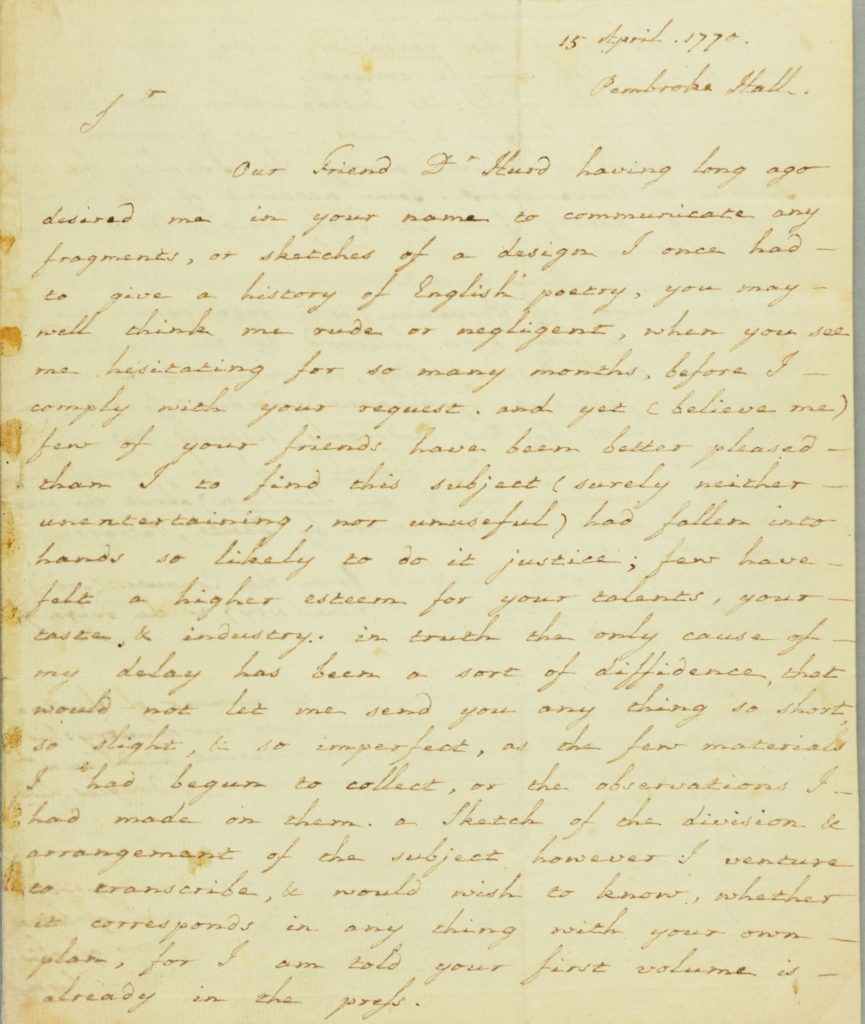

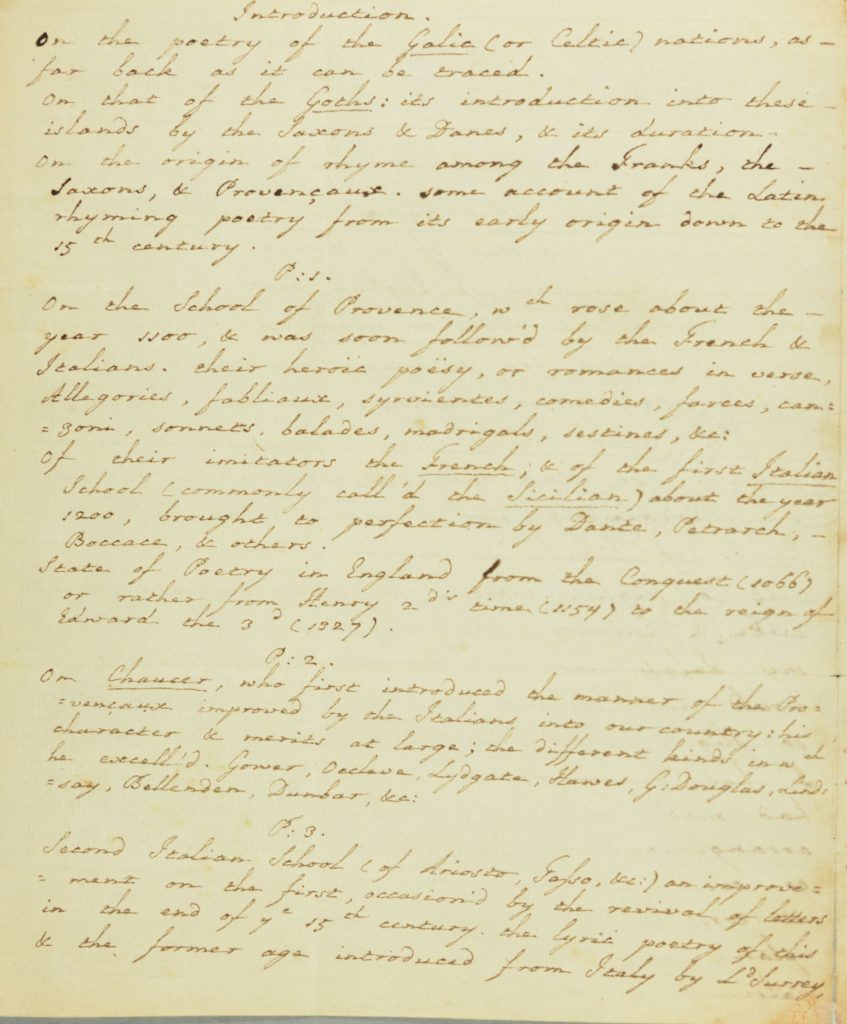

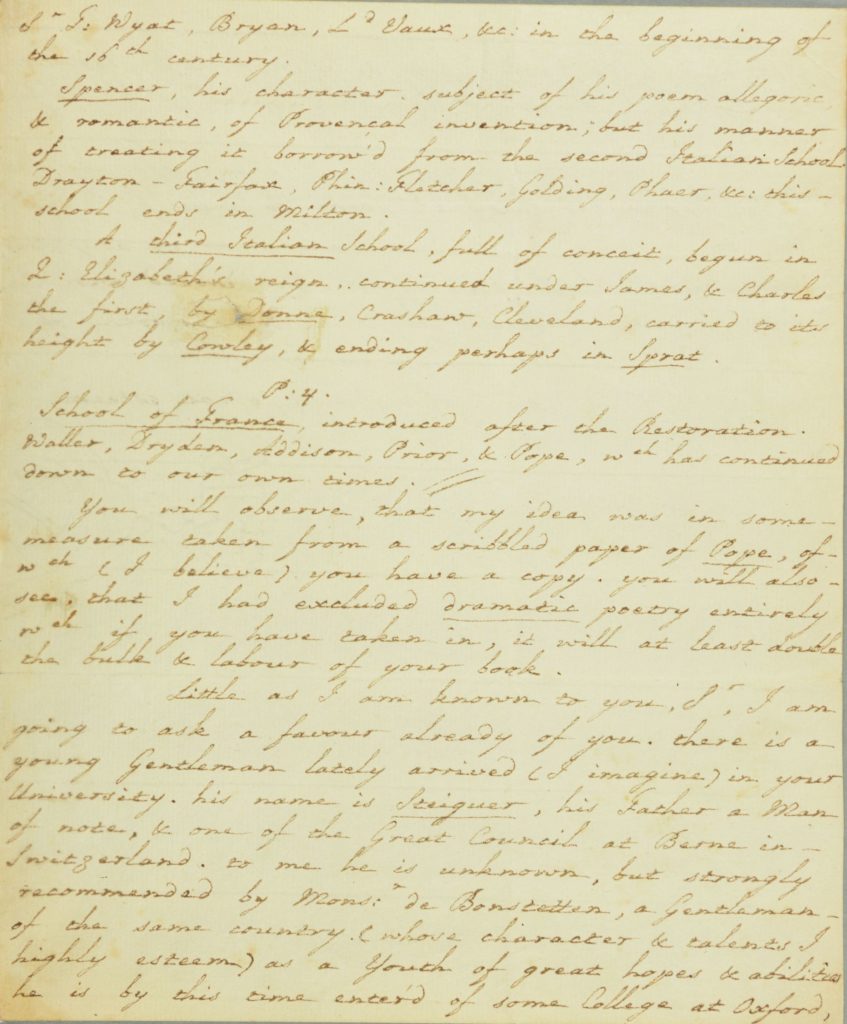

Gray’s letter to Thomas Warton

Thomas Gray, letter to Thomas Warton containing an outline for a history of English poetry, Cambridge: 15th April 1770 [MS 316]

Long before the Romantics revived interest in Celtic and Norse mythologies, Gray began work on a comprehensive ‘history of English poetry’. Beginning with Celtic literature, Gray gathered information from little-known medieval sources.

The same scholarship that had been fostered at Eton was present throughout his life, and though he relied on Latin translations of ancient Welsh poetry Gray found that he could ‘perceive… something of the measure, alliteration, and order of rhymes’. Gray died one year after this letter was written, his history of English poetry unfinished. Nevertheless, the ancient songs and styles that he studied worked their way into his later poems.

Nature, the picturesque and the sublime

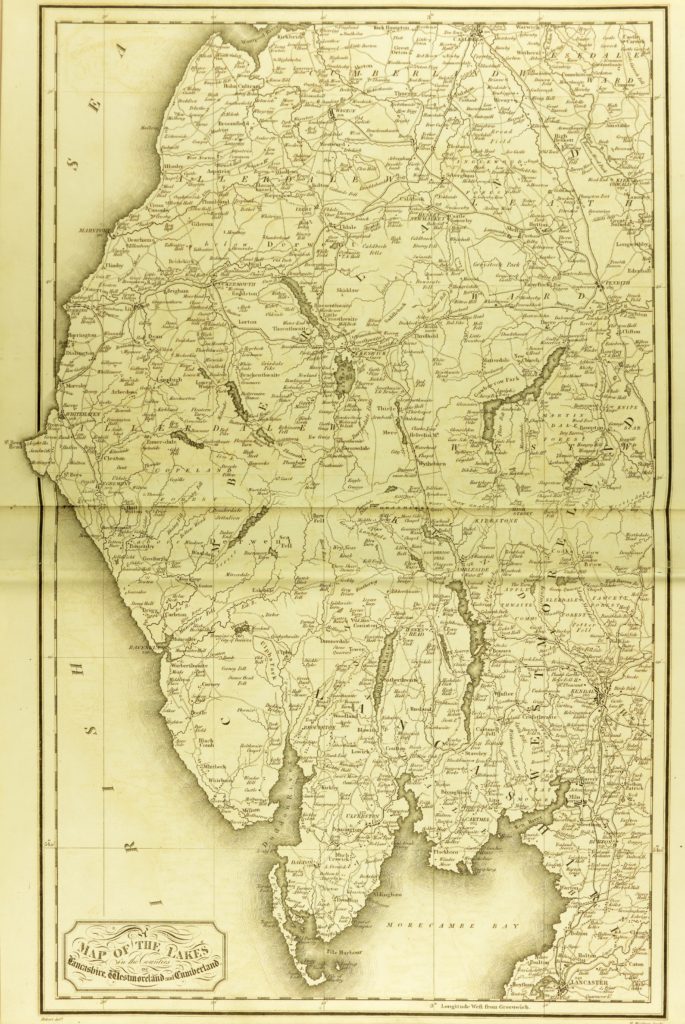

Engraving from a drawing by Joseph Farington in Thomas Hartwell Horne, The lakes of Lancashire, Westmorland, and Cumberland, London: T. Cadell and W. Davies, 1816 [Ca.1.09]

For Gray as for the Romantics, nature was a source of solace and a place for introspection. Gray’s poetry often places poet and reader in a solitary scene; ‘Elegy Written in a Country Churchyard’ begins with the poet-figure in a picturesque setting, left alone ‘to darkness and to me’. But nature was also the setting of encounters with the sublime, where imagination and sensibility transformed the landscape into something awe-inspiring or even terrifying. In ‘The Bard’, Snowdon’s ‘haughty brow frowns’ with the same hostility as the Bard himself.

In 1769 Gray set out on a tour of the Lake District. His travelling companion became unwell and could not accompany him, so Gray kept a written account in his journals, which he later sent to his friend as letters. Gray’s Journal of his Tour in the Lake District was published in 1775, four years after his death. Gray, who had studied travel writing at Peterhouse, may have been amazed to know that his private travel journal would become one of his most popular works.

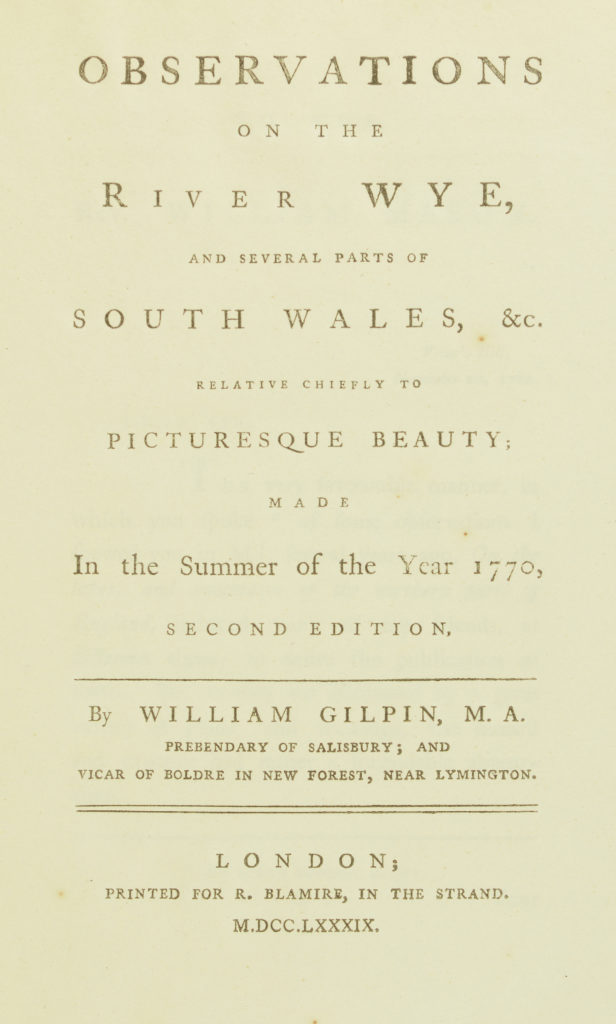

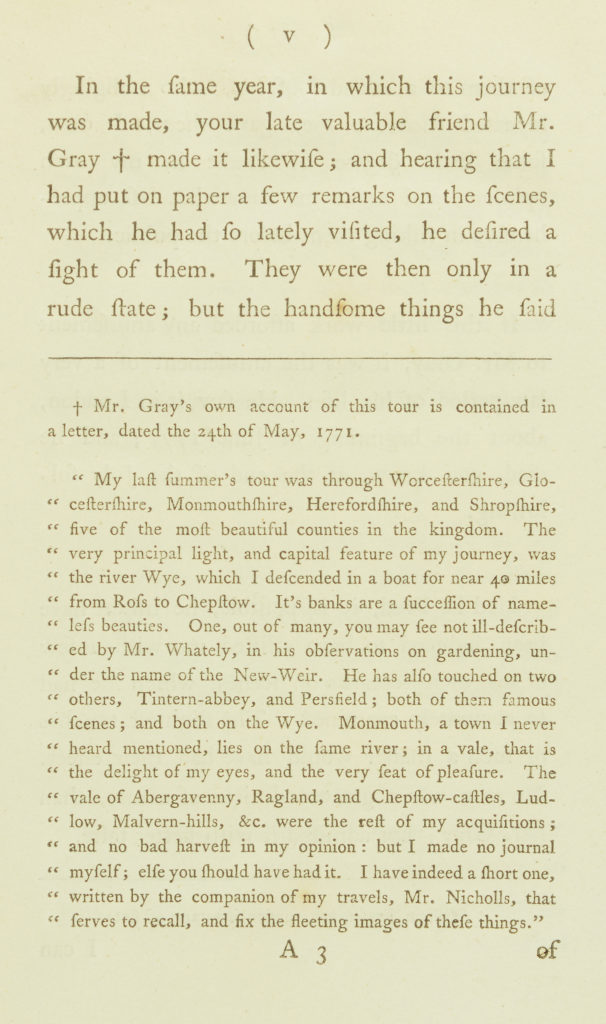

Gray encouraged his friend William Gilpin to write his Observations on the River Wye. Published in 1782 and followed by a companion volume on the Lake District, Gilpin’s book established England and Wales as the setting for a sort of British Grand Tour, where crowds of tourists could encounter dramatic, sublime landscapes and picturesque scenes.

Gray, the Poet… died soon after his forlorn and melancholy pilgrimage to the Vale of Keswick, and the record left behind him of what he had seen and felt in this journey, excited that pensive interest with which the human mind is ever disposed to listen to the farewell words of a man of genius.

William Wordsworth, Select Views in Cumbria, Westmorland, and Lancashire, 1810

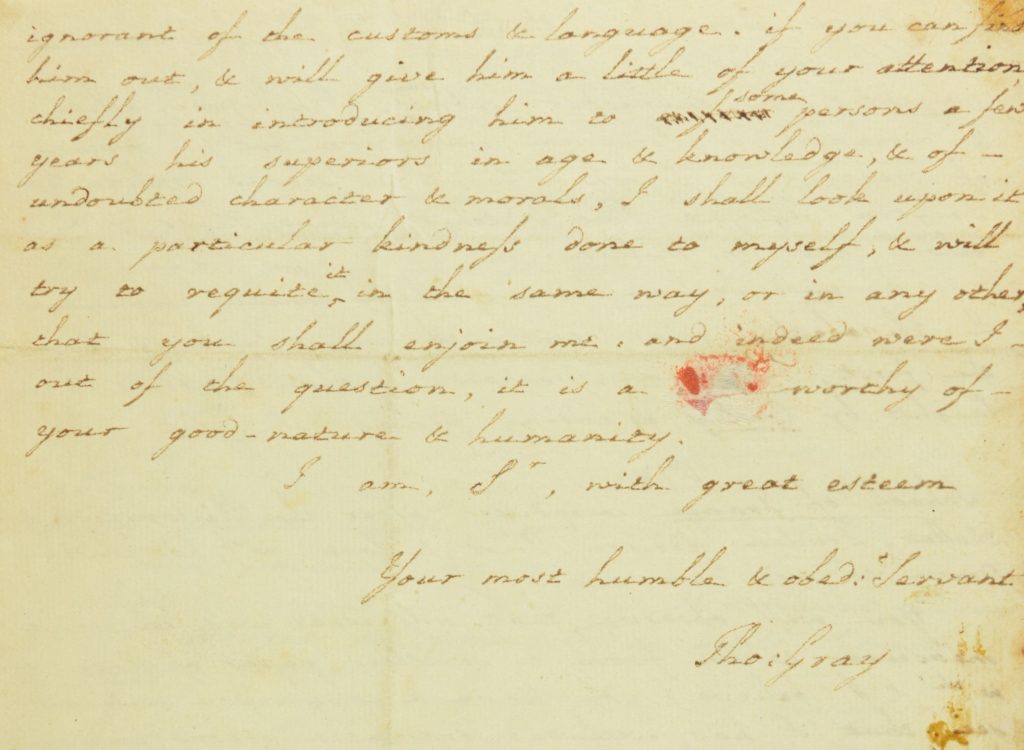

William Gilpin, Observations on the River Wye

William Gilpin, Observations on the River Wye, London: R. Blamire, 1789 [Cl.4.17]

Gilpin and Gray were friends and correspondents. Having read Gray’s travel account Gilpin shared his own manuscript with him. Gray and William Mason encouraged him to seek publication, and Observations on the River Wye was published in 1782, with an additional work on the Lake District following in 1786. Gilpin set out a theory of the picturesque in nature, ‘that peculiar kind of beauty which is agreeable in a picture’, in which beauty and the sublime enhance one other.

In the preface Gilpin writes that ‘no man was a greater admirer of nature, than Mr. Gray; nor admired it with better taste.’

Engraving from a drawing by Joseph Farington in Thomas Hartwell Horne, The lakes of Lancashire, Westmorland, and Cumberland, London: T. Cadell and W. Davies, 1816 [Ca.1.09]

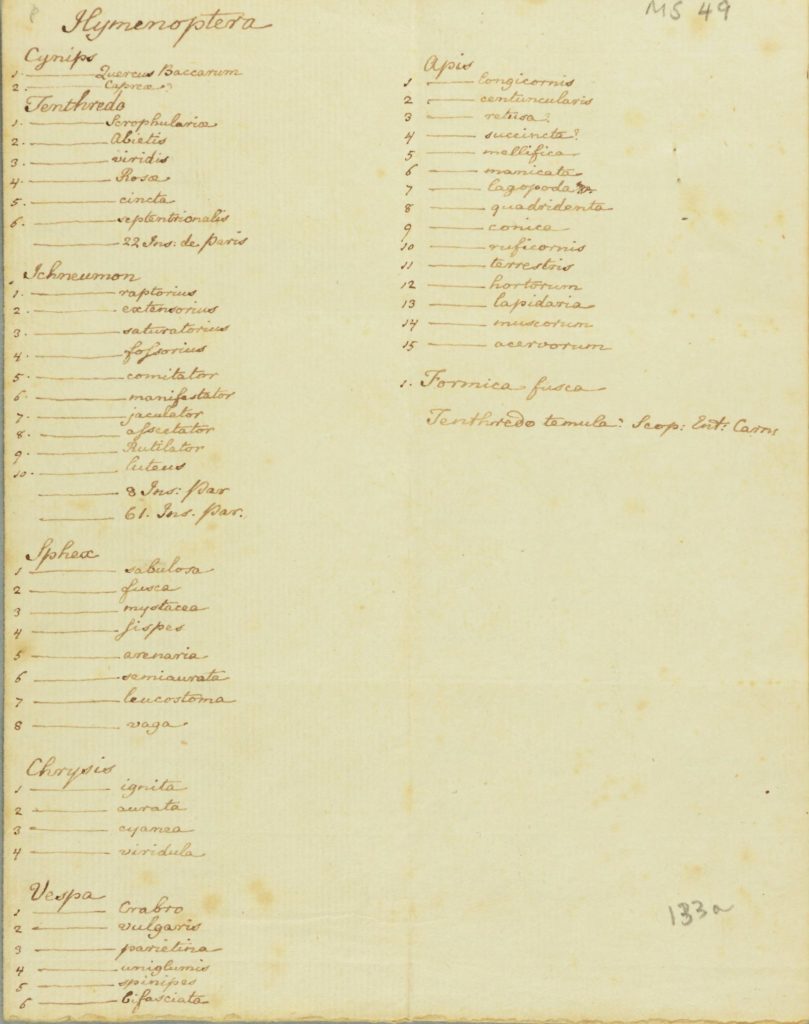

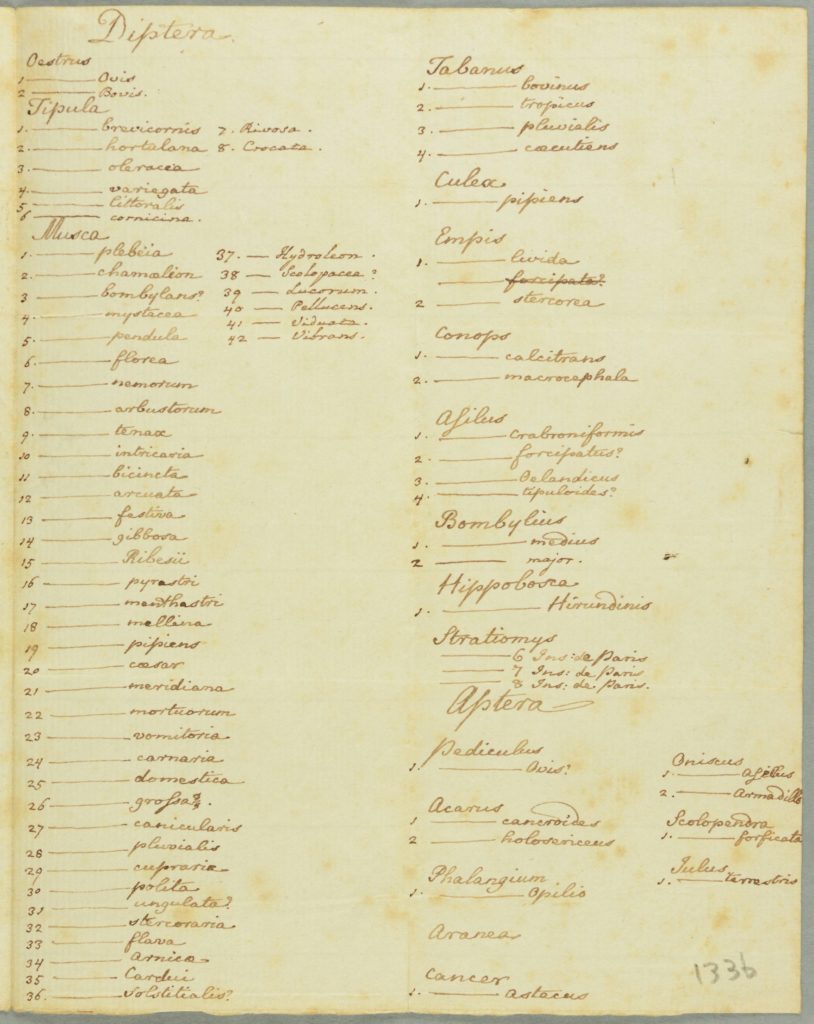

Gray’s notes on insect species

Thomas Gray, A list of insect species under the headings hymenoptera and diptera, England: mid to late 18th century [MS 49]

Gray remained a rigorous academic to the end of his life, and his appreciation of nature was scientific as well as aesthetic. In 1759 Gray purchased a copy of Carl Linnaeus’s Systema Naturae, in which the Swedish zoologist set out his taxonomy of species, and interleaved it with extensive notes, drawings and Latin verses. It is likely that this autograph manuscript was created during the same period, and indeed may be a loose sheet that escaped interleaving. Gray has listed hymenoptera, insects with two pairs of wings, and diptera, which have a single pair of wings, according to Linnaeus’s nomenclature.

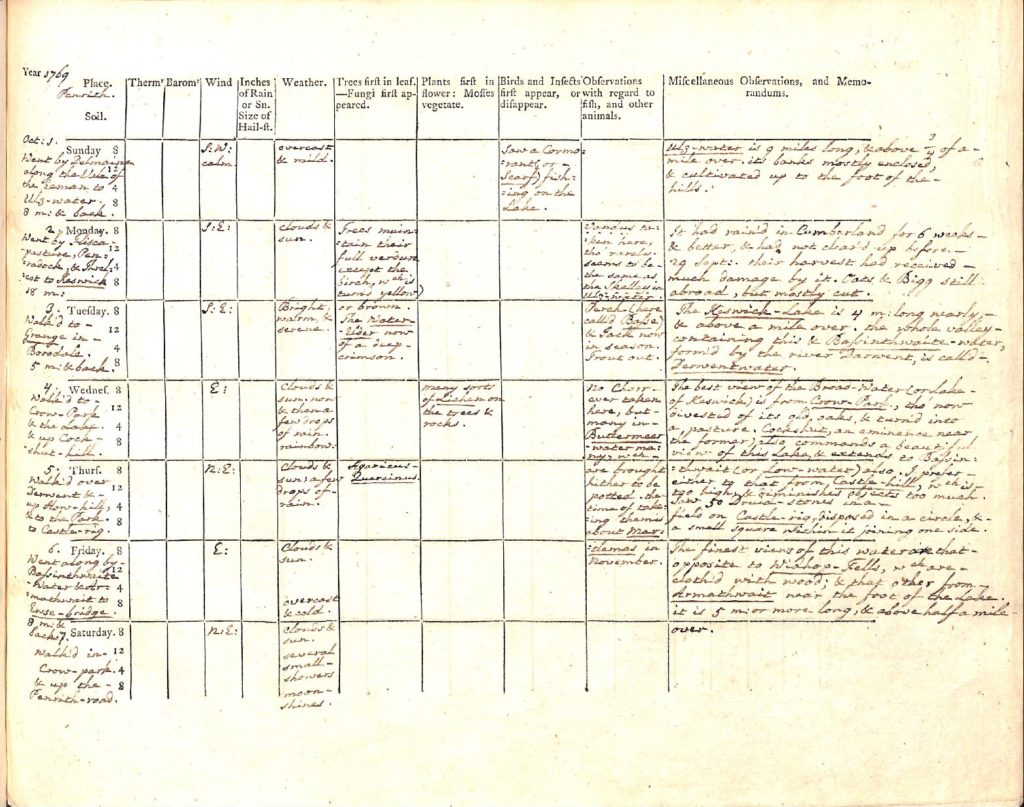

Gray’s Naturalist’s Journal

The naturalist’s journal, London: W. Sandby, 1767; with manuscript notes by Thomas Gray [MS 954]

Gray’s maternal uncle Robert Antrobus was an Assistant Master at Eton, and instilled a love of botany in the young scholar which would continue throughout his life. Gray filled this printed naturalist’s journal with daily observations in English and Latin. It is unlikely that he took this large book with him on his travels, but here he has carefully recorded observations on weather, flora and fauna made on his famous journey through the Lake District. He continued to add to this journal until two months before his death, on 30th July 1771.