Montem, a peculiar and spectacular Eton ceremony where boys would process ad montem (‘to the hill’), was celebrated for centuries. First recorded in 1561, it is believed that Montem began as an initiation ceremony for boys. By the 19th century it had become a grand pageant, in which Etonians processed in elaborate ceremonial and military dress from the College to Salt Hill in Slough. Huge crowds flocked to see the procession, glimpse attending royalty, and participate by giving money in exchange for a pinch of salt or, later, a paper ticket.

Although some felt that the excesses of the occasion were merely the performance of an ancient ritual, by its final decades many felt that Montem had become an excuse for frivolity and immorality. It became a victim of its own success. School leaders ultimately decided that the boys’ behaviour was unacceptable, as were national attention thanks to royal patronage, and increasing crowds, aided by developments in coach and train transport. The ceremony was abolished, with the final Montem taking place in 1844. Less controversial traditional ceremony and school events continue to be important to Eton, however, through celebrations such as the Fourth of June, a summer event featuring the Procession of Boats.

Clothing, ephemera and written accounts provide glimpses into Montem, a unique example of intangible heritage. Its customs incorporated school hierarchy, student organisation and teamwork, comedic oratory and identity as Etonians, both while pupils at the school and later, as adults. Alumni were a core part of the Montem audience, which for many was a day of reminiscence and reinforcement of their lifelong connection to Eton.

There are few, if any, records of the earliest Montem ceremonies, which relied on handed down experience and etiquette. We can, however, recover much more about the final century of increasingly immoderate Montem festivities. This exhibition traces the traditional event, from its ambiguous origins to its abolition through historic artwork, archival records and rare surviving examples of ornate costume. It also examines reminiscence, reuse and restoration at play in the scarce representatives of historic children’s clothing that remain.

William Evans (1798-1877), The School Yard: Fourth June, print, 1852 (FDA-E.343-2010)

This print shows the beginnings of the Montem procession which started in School Yard. Boys would circle the yard amidst band music before heading out to Montem Mound. It was a vibrant scene, captured by Benjamin Disraeli in his novel Coningsby (1844):

Five hundred of the youth of England, sparkling with health, high spirits, and fancy dresses, were now assembled in the quadrangle. They formed into rank, and headed by a band of the Guards, thrice they marched round the court. Then quitting the College, they commenced their progress ‘ad Montem’. It was a brilliant spectacle…

Charles Turner (1774-1857), Salthill, Montem, pencil and watercolour, c.1820 (FDA-D.510-2010)

Here the procession has reached Salt Hill, the area along Bath Road in Slough where Montem Mound is situated (the mound can be seen on the right side). The Windmill Inn, or Botham’s, is on the left, hosting audiences watching the procession from its windows and gardens.

The younger boys can be seen wearing the ‘old Eton uniform’ of blue jackets. Pages are ornately dressed, as is the Salt Bearer who stands centre right wearing a white turban. In one hand he holds a salt bag which looks full of gathered donations. Two boys in the lower right corner look to be having an altercation, it is likely one is trying to wield his sword to slice the Montem pole held by the other.

Montem Salt Bearer’s outfit, 17th-century style, early 19th century (MEL.441:1-5-2010)

Ornate fancy dress was worn especially for the event. This purple silk velvet and yellow silk outfit is intricately decorated with metal thread braid and bobbin lace. The skirt has small weights stitched into the hem to ensure it falls in a particular way.

Runners (or ‘Servitors’) woke at dawn to travel to outlying districts (Windsor Bridge, Colnbrook, Maidenhead Bridge, Salt Hill, Slough, Datchet Bridge, Iver and Gerrards Cross) to collect money. They would return to Eton to deliver their takings to the Salt-Bearers, who carried them in the procession. The two Salt Bearers tended to be at the rear of the procession; exquisitely dressed in vibrant silks, velvets and gilt metal, with plumed hats and carrying the ‘salt’ in matching velvet bags.

Richard Livesay (1750-1826), The Montem Procession, oil on canvas, c. 1793 (FDA-P.52-2010)

The main focus of Montem was the vibrant procession of Etonians that travelled from Eton to the mound on the Great Bath Road. Organised by the students, this hierarchical procession included boys of different ages and positions in the school, and in later years followed a military structure. Each boy had roles to play, with varying actions to carry out and costumes to wear.

Richard Livesay embarked on a highly ambitious project to create this panoramic painting of the whole Montem procession. Individual portraits of each of the participating boys, in the outfits and positions they occupied during the procession, were made in preparation for this work. It was a huge task in the days before photography to capture hundreds of likenesses and unsurprisingly the painting remains unfinished. Regardless, this painting remains a valuable visual record of the Eton Montem procession. It was presented to Eton College by Henry Pelham-Clinton, 7th Duke of Newcastle in 1891.

Unknown artist, after Samuel Hieronymus Grimm (c.1733-94), Eton Montem 1778, drawing, after 1778 (FDA-D.1365-2015)

Although Montem started as an initiation ceremony, it evolved into a grand fête for the whole school, drawing royal patronage and public attention. After King George III first attended in 1778 it became an even grander affair, reported in national media.

The attendance of royalty had an impact on the structure of the day and attracted increasing numbers of visitors to the event. No one, whether King or humble passer-by, escaped the call for salt; the King or Queen gave £50, and other royal figures gave sums up to £50. Prince Albert, the final royal to attend Montem, gave £100 in 1844 (the relative value today would be over £10,000).

Charles Turner (1774-1857), Battiscombe and the Duke of Buccleuch waving the Montem flag, drawing, 1820 (FDA-D.582-2010)

A preparatory drawing for the larger artwork Salthill, this sketch shows Walter Francis Montagu Douglas Scott (1806-84), self-styled Earl of Dalkeith between 1812 and 1819, later 5th Duke of Buccleuch and 7th Duke of Queensbury. He was the son of the Earl of Dalkeith who was also painted in Montem dress. In this drawing he is waving the Montem flag, a role assigned to the Ensign. At the 1820 Montem he would have been aged 14.

Beside him is George Frederick Battiscombe (1810-36), who arrived at Eton in 1816 and was aged 9 for the 1820 Montem. George is shown in his costume in two positions, and his age, dress and inclusion in the work suggests that in the 1820 Montem he was the Page for the Douglas Scott.

Montem Salt Bearer’s bag, used in the 1838 Montem (MEL.432-2010)

There was more to Montem than dressing up. A suite of objects were central to the day’s events. From the paper tickets given out in place of salt, or sold to grant access to various locations throughout the day, such as entry to breakfast at the College or dinner in the gardens of the Windmill Inn, to the velvet, silk and gilt metal bags that were carried by the Salt Bearers in which to collect the day’s raised funds, only a few of these objects from centuries of Montem survive.

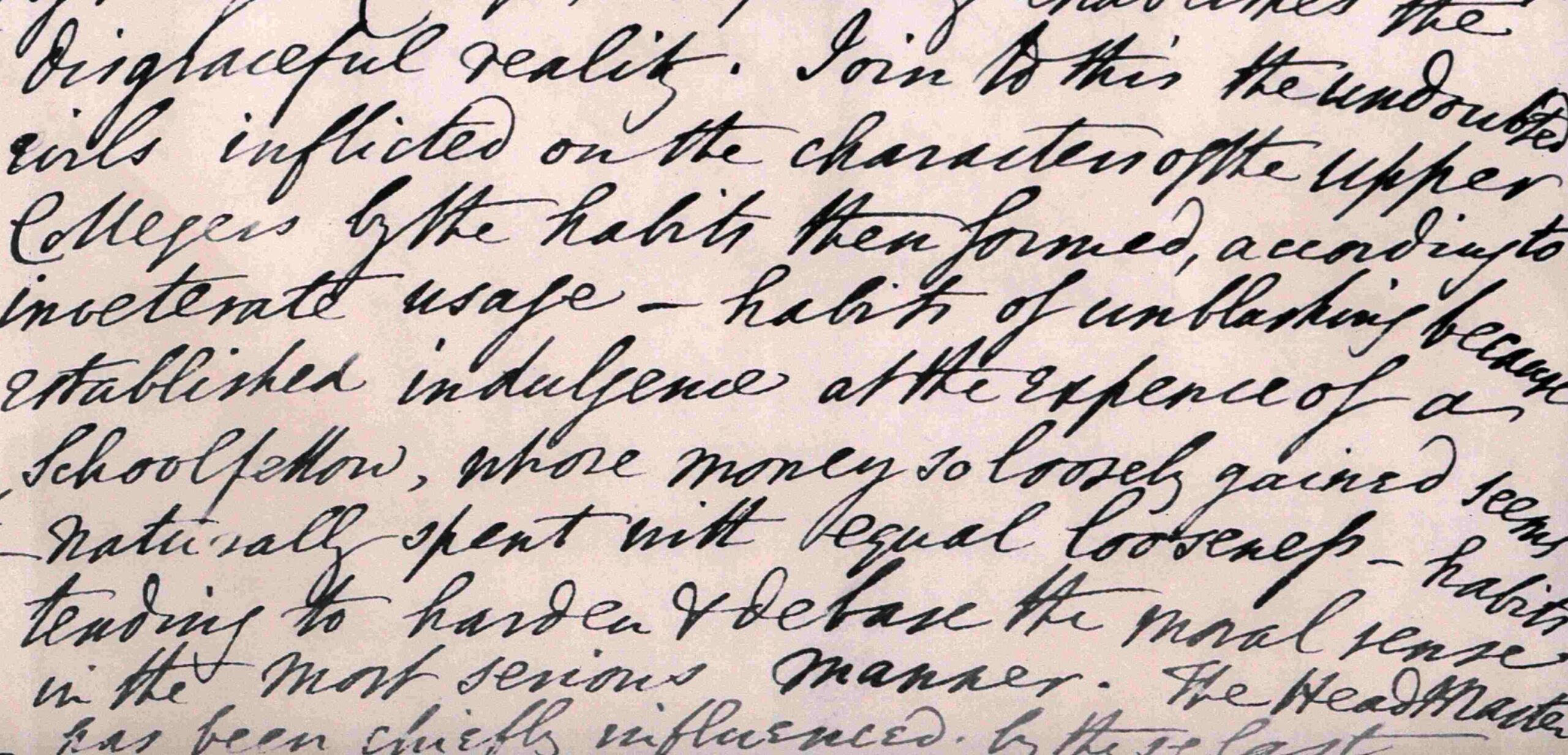

Excerpt from copy letter from Provost Hodgson to George Howard, Lord Morpeth (later 7th Earl of Carlisle), 19 November 1846 (ED 531 04)

By the 19th century, although many were still in favour of Montem, there were also increasing arguments against the event, notably regarding the manner of fundraising, influx of crowds and the misbehaviour of the boys. Provost Francis Hodgson (1840-53) criticised the ‘meanness’ of Montem which caused injury to the Captain of the School and instilled bad habits into boys long after the day itself:

‘to say that this occurs only once in three years, is to make good morals occasional…’

…Join to this the undoubted evils inflicted on the characters

of the Upper Collegers by the habits then formed, according

to inveterate usage – habits of unblushing because established

indulgences at the expense of a schoolfellow, whose money so

loosely gained seems naturally spent with equal looseness –

habits tending to harden & deface the moral sense in the most

serious manner…

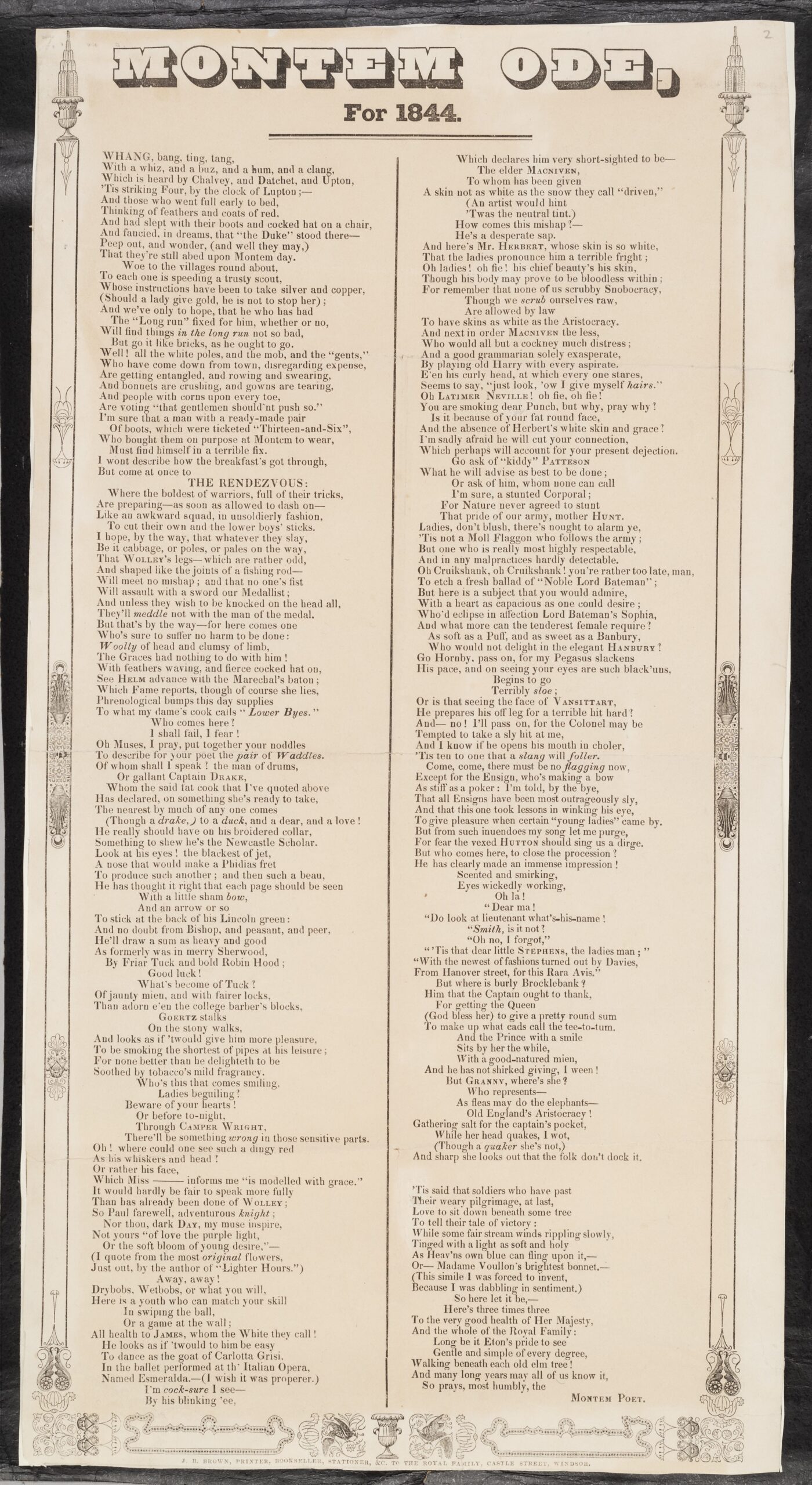

Montem Ode, 1844 (SCH P 08 03)

From the 1770s onwards, the Montem ceremony featured an ode written by the Montem Poet for the occasion. Printed for sale to visitors, the odes consisted of punning doggerel rhymes featuring the names of key participants. This example from 1844 would be the last to be written.

In 1846 the school announced that there would be no Montem in 1847; May 28 1844 retrospectively became the final Montem, ending centuries of this historic and unique Eton ceremony.

Montem Salt-Bearer’s outfit, 17th-century style (MEL.451:1-4-2010)

This blue and cream silk outfit, embellished with metal wrapped thread, was worn by John Phillipps Judd for a Montem in the 1820s, and is based on the court dress of adults from the 17th century. This outfit offers a good example of alterations made for reuse. The inside of the sleeve shows that it has been taken up and the addition of a panel in the centre back suggests that the jacket had been narrower earlier in its life. Perhaps Judd wore it more than once as he grew or it was passed down to a younger friend or relative.

Photograph of Cecil Millett in Montem costume, 1912 (SCH LIB 06 01)

The costume was originally worn at Montem by George Harcourt, Millett’s grandfather, in 1823. Millett wore it in 1912 for a fancy dress ball.

The catalogue for the exhibition held at Eton in 2023 may be downloaded below.