Explore the exhibits:

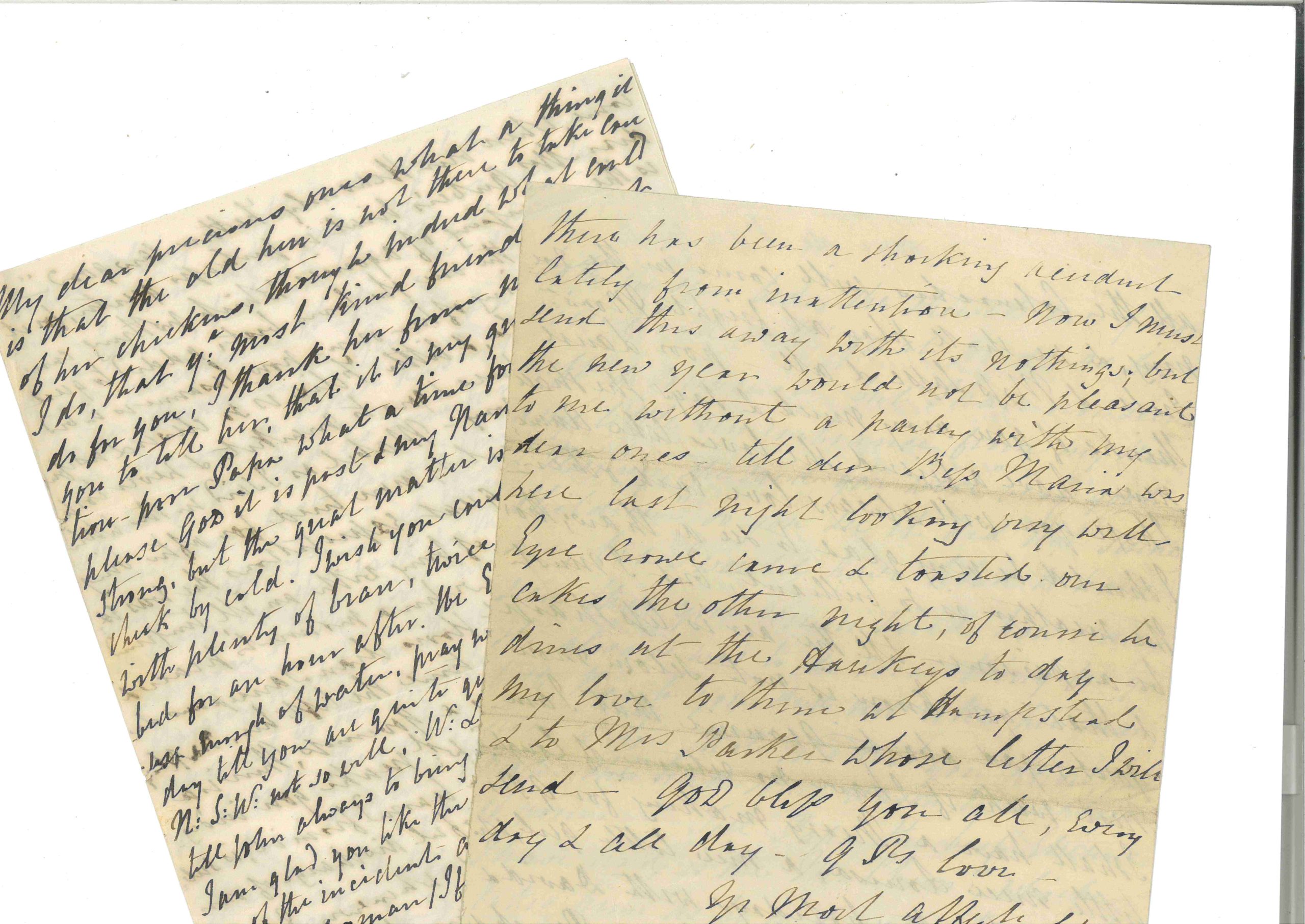

Letters from Anne Carmichael-Smyth to Annie and Minnie Thackeray (1848-1852) Eton College Library [MS 430/01/01/02]

Anne Carmichael-Smyth was extremely fond of her granddaughters, and wrote to them regularly after they returned to live with their father, signing the letters ‘old Grannie’, giving updates on Paris life and often providing her thoughts on society. In a letter dated 22 April 1852, she encourages her granddaughters to pursue their own interests, stating ‘In France women are a deal more actively employed… What is to prevent women from studying and making it a profession?’

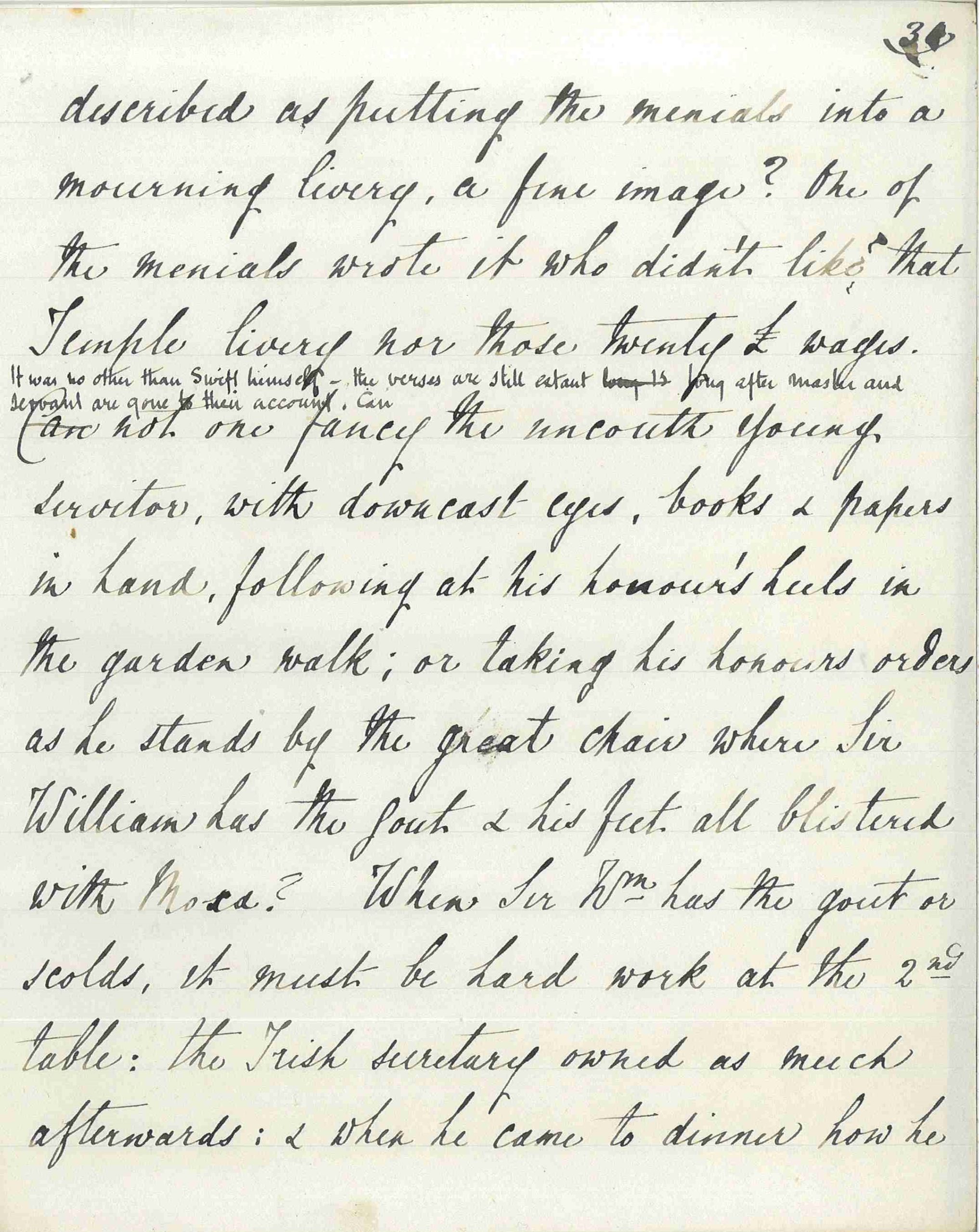

Manuscript page from William Makepeace Thackeray’s lecture on Jonathan Swift, in Anne Thackeray’s hand (c.1850s) [private collection]

This manuscript is a rare surviving example of Annie acting as her father’s amanuensis, bringing her patience and humour as her father struggled with composing his work. She would record what he dictated, and he would then correct the manuscript afterwards.

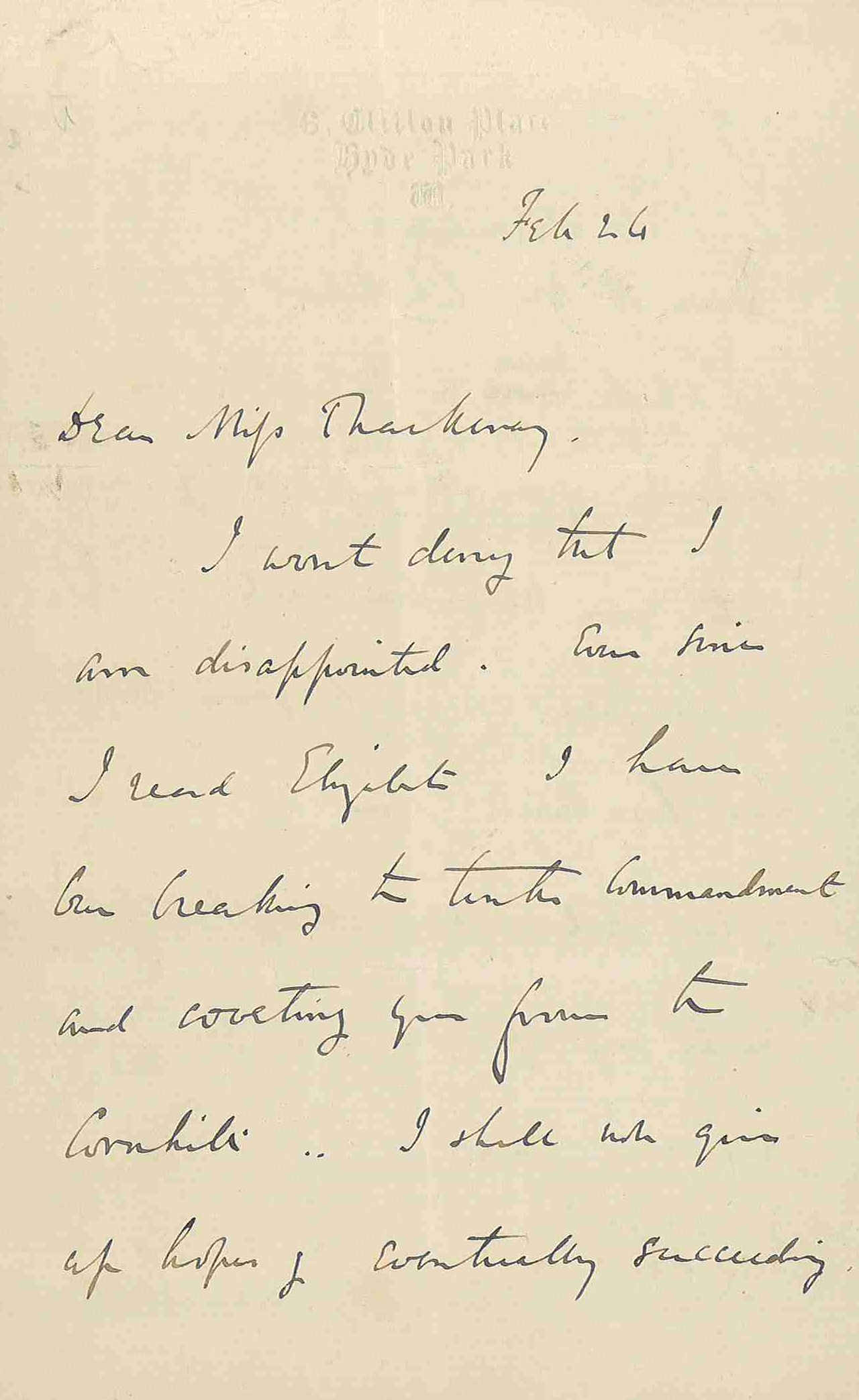

Letter from George Smith, editor of The Cornhill Magazine, to Anne Thackeray regarding Denis Duval (4-6 May 1864) [private collection]

This letter from George Smith, who had succeeded Thackeray as editor of The Cornhill Magazine in 1862, confirm Annie’s role in the posthumous publication of her father’s last novel, left unfinished at his sudden death aged just 52.

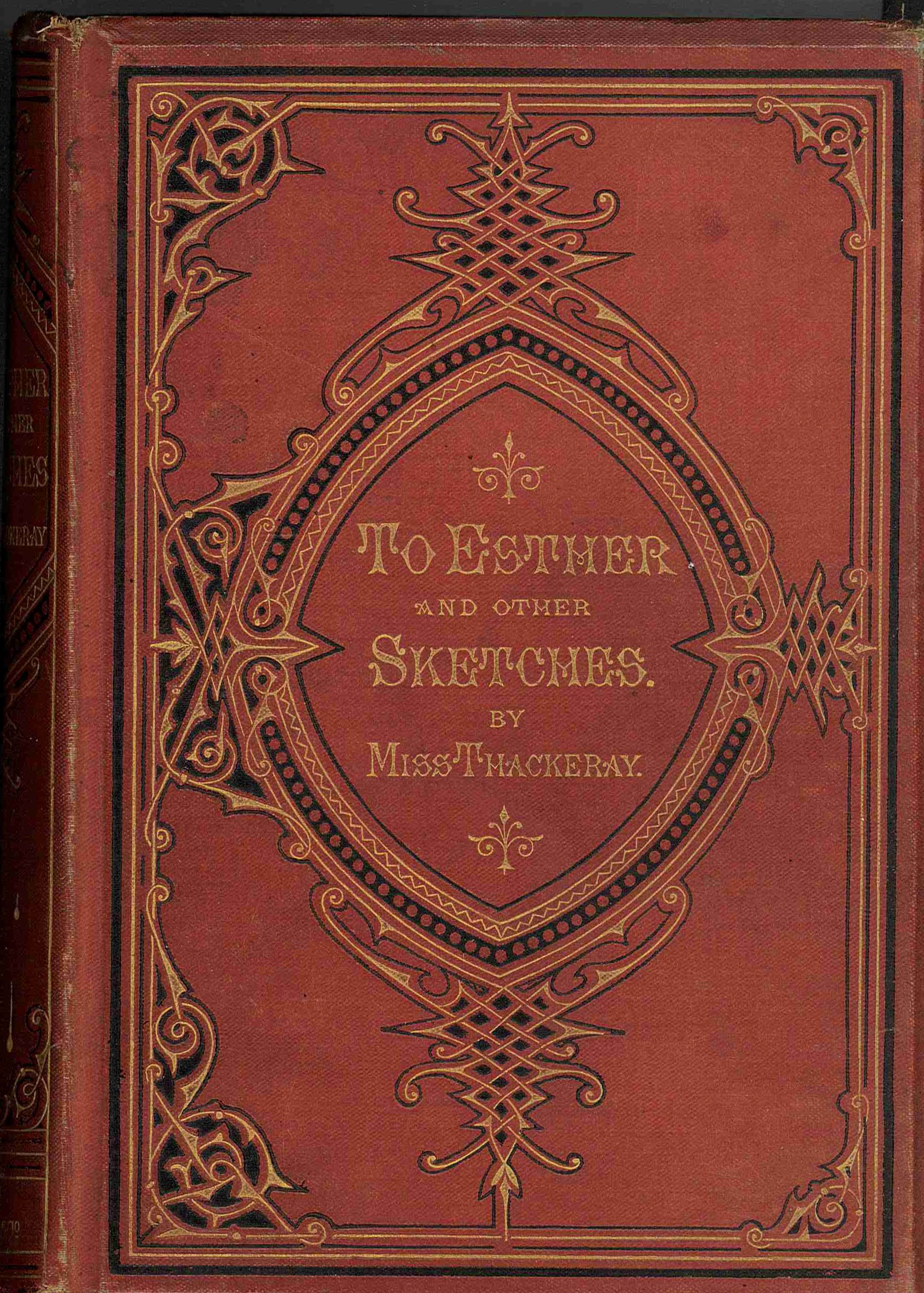

Anne Thackeray, To Esther and Other Sketches (London: Smith, Elder & Co., 1869) Eton College Library [Icc4.1.30]

Annie wrote a number of other short pieces for The Cornhill Magazine and remained fond of her early writing, agreeing for some articles to be republished together in this volume.

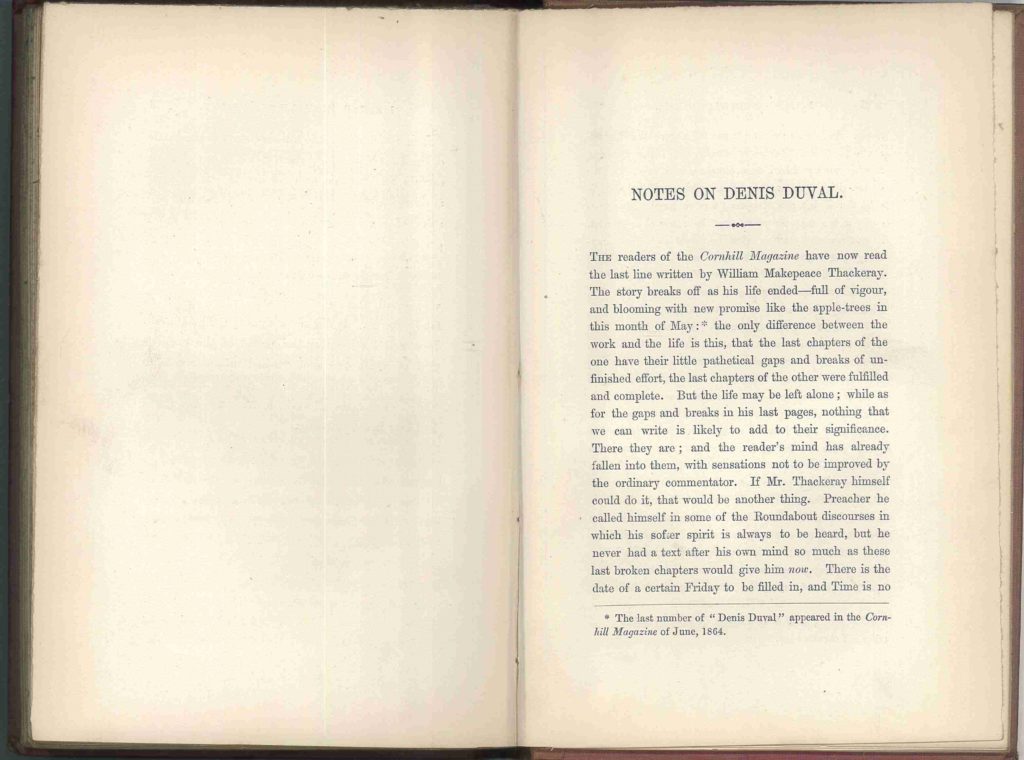

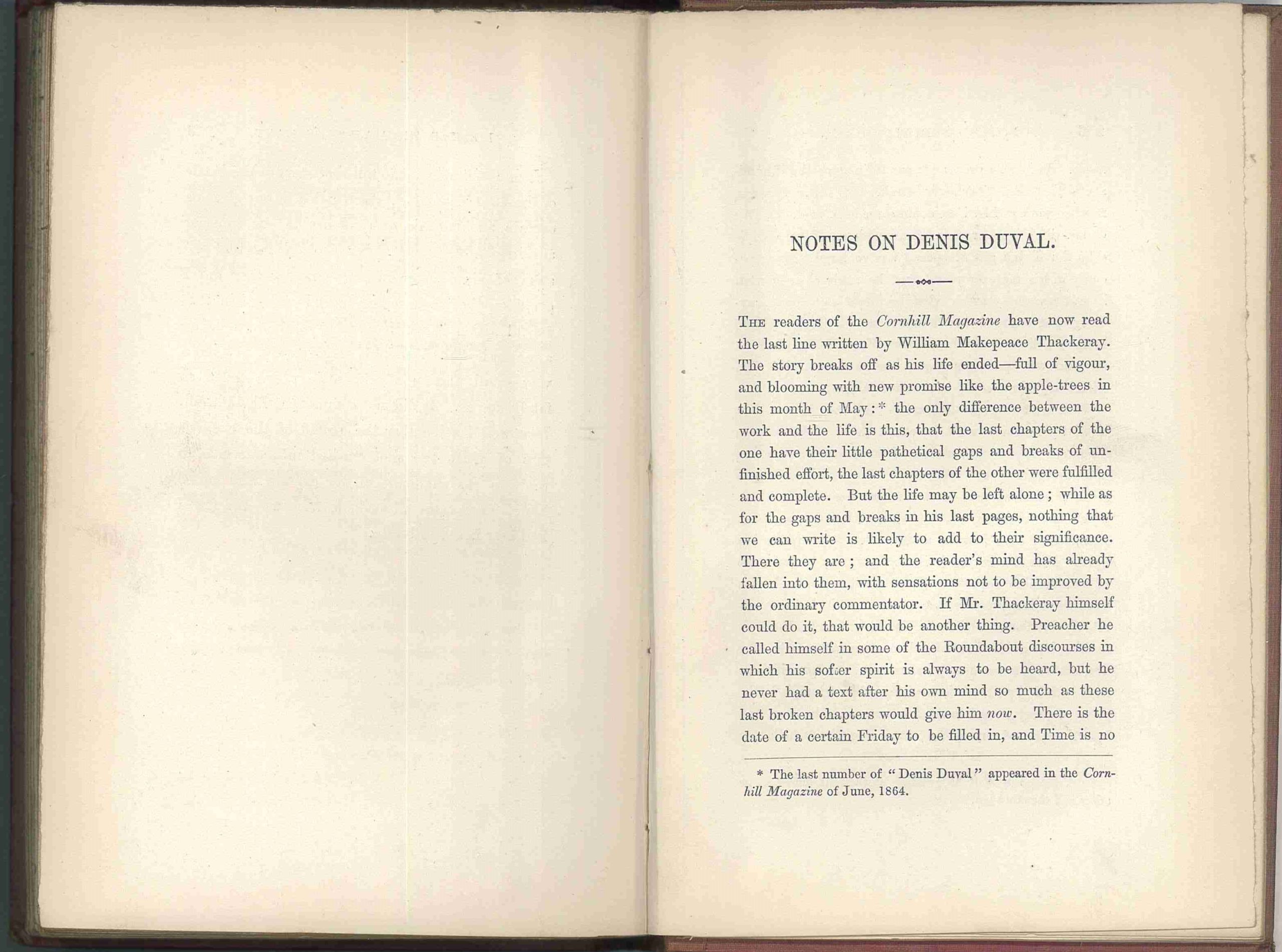

Proof sheets of William Makepeace Thackeray, Denis Duval (London: Smith, Elder & Co., [186–]) Eton College Library [Id5.5.19]

Thackeray’s last novel, left unfinished at his death, was published in The Cornhill Magazine from March to June 1864, concluding with a ‘Note from the Editor’ written by his daughter to complete the story. This is proofs of the first London edition in one volume, published in 1867.

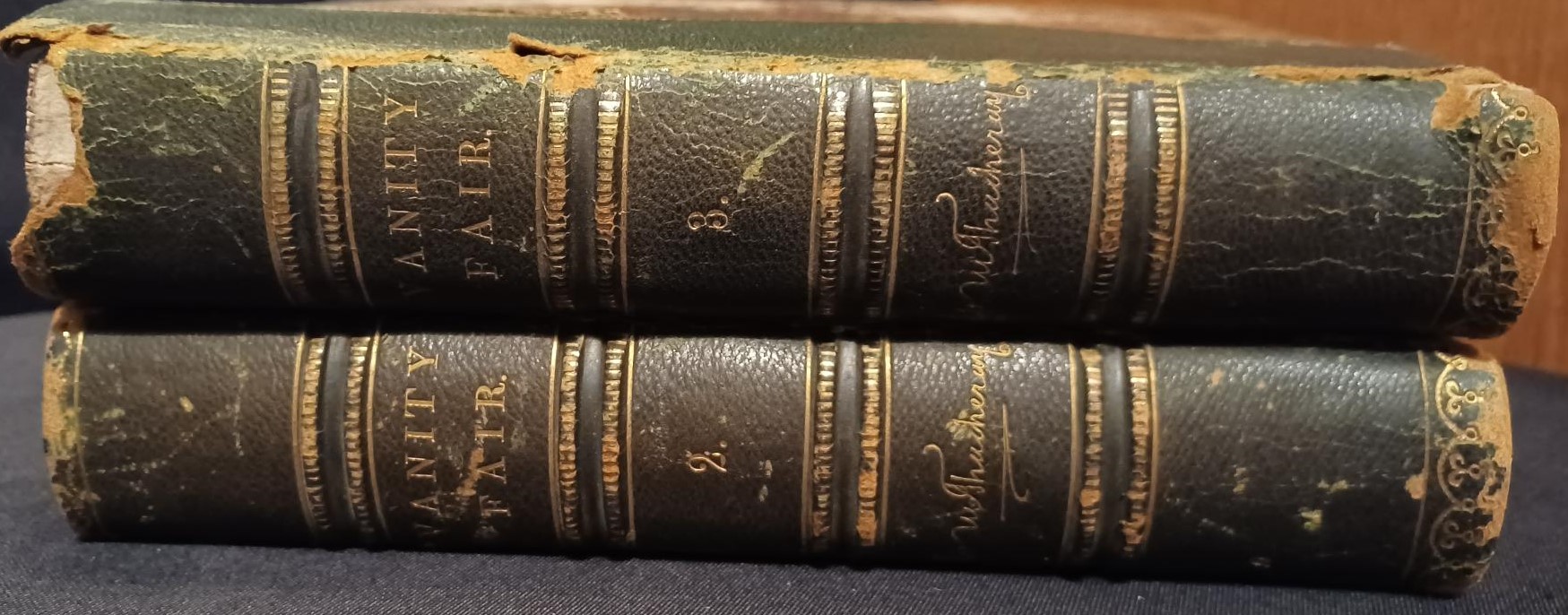

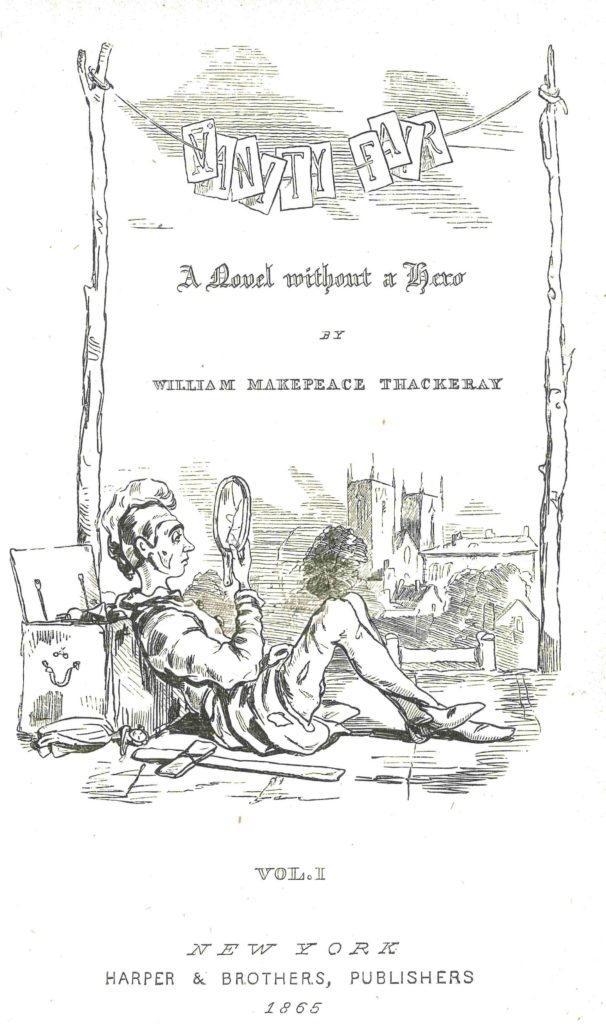

William Makepeace Thackeray, Vanity Fair (London: Bradbury and Evans, 1848) Eton College Library [Icc4.1.09]

Thackeray’s most famous novel was first published as a monthly serial from 1847-48, and printed in two volumes in 1848. The ‘Novel without a Hero’ follows the lives of two young women, the social climber Becky Sharpe and her school friend Amelia Sedley, and satirised early 19th-century British society. Highly praised at the time, the work continues to inspire adaptations on film and television.

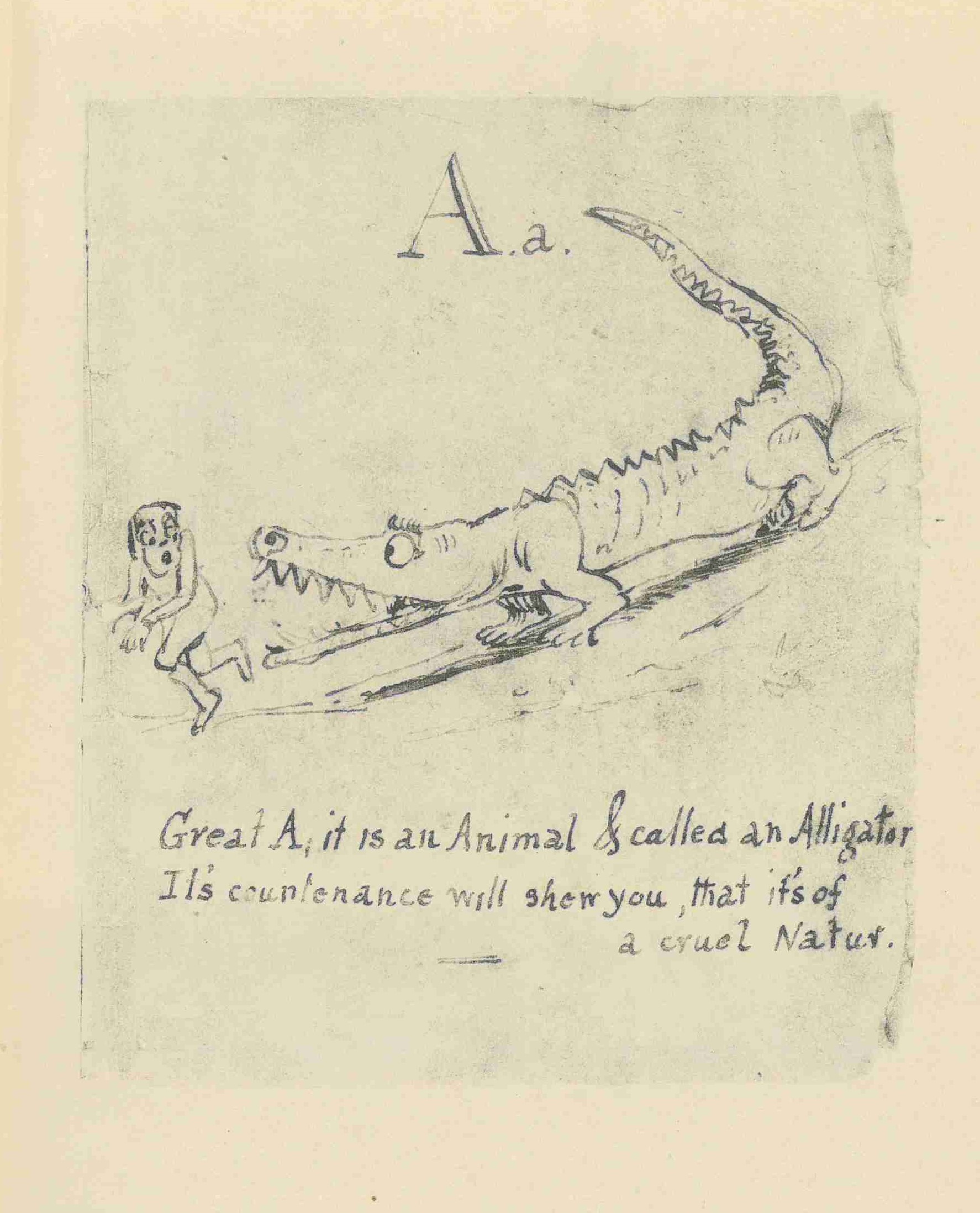

William Makepeace Thackeray, Alphabet (London: John Murray, 1929) Eton College Library [Icc4.1.10]

This short ‘abecedarium’ was created by Thackeray around 1833 during a visit to Sherborne, Dorset, where he was calling on the parents of Edward Frederick Chadwick. There he was ‘ushered in on a scene of woe—a small boy sobbing in a corner’. The cause of young Eddy’s grief was having to learn his alphabet, which Thackeray agreed was ‘such a dull thing to learn’. The facsimile published by Eddy’s son shows Thackeray’s light-hearted approach to education that was likely instilled in his daughters as he encouraged them to embrace their childish imaginations.

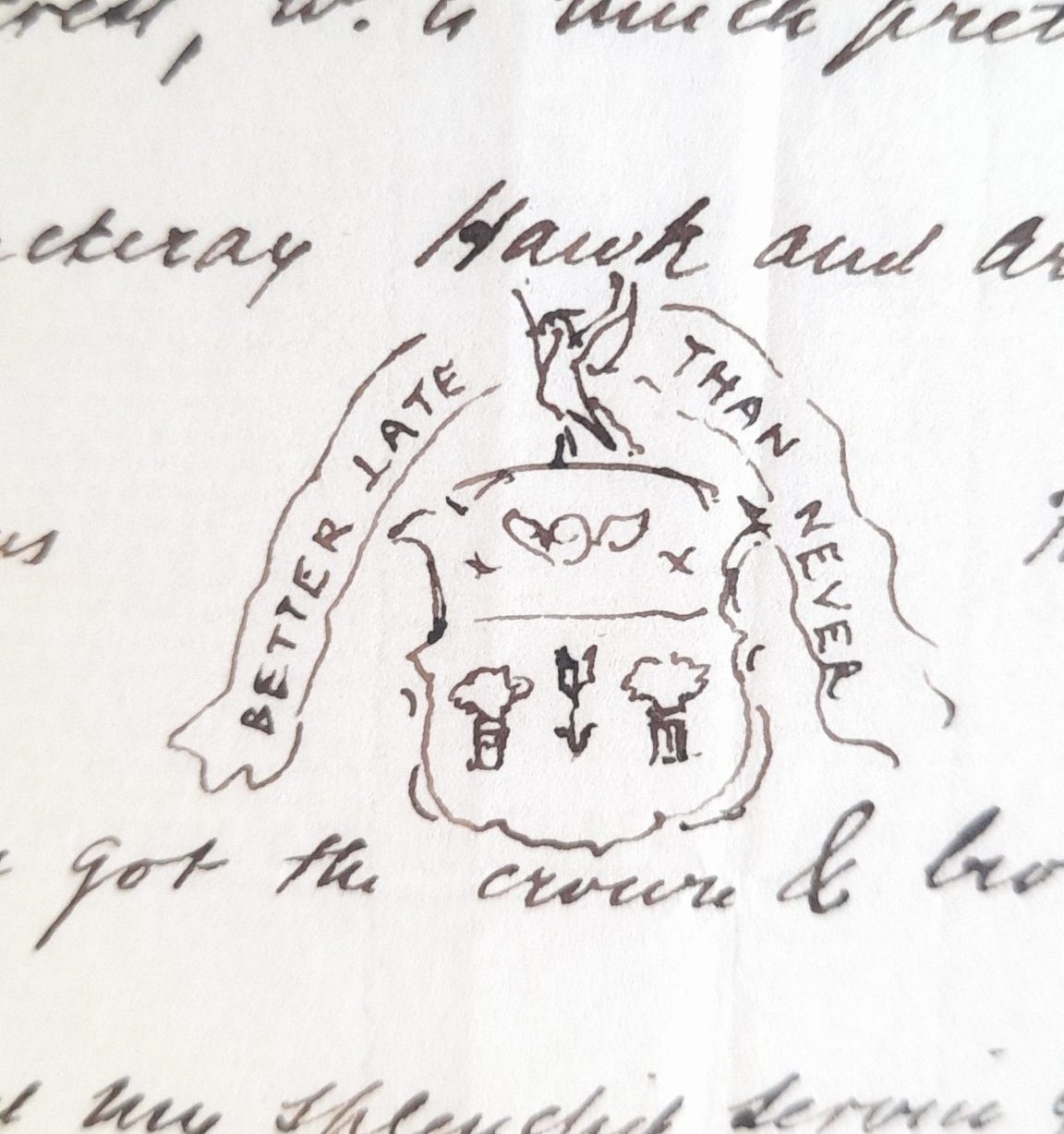

Sketch of the Thackeray coat of arms by William Makepeace Thackeray (n.d.) Eton College Library [Knn.2]

Detail of the Thackeray coat of the arms which William Makepeace Thackeray used to illustrate a letter, where he discussed the family pedigree

Photograph of Annie and Minnie Thackeray (c.1854) Eton College Library [MS 430/01/05/01]

With both their mother and father absent for much of their childhood, Annie and Minnie sought stability and friendship in each other, and they formed a strong bond that both treasured their whole lives.

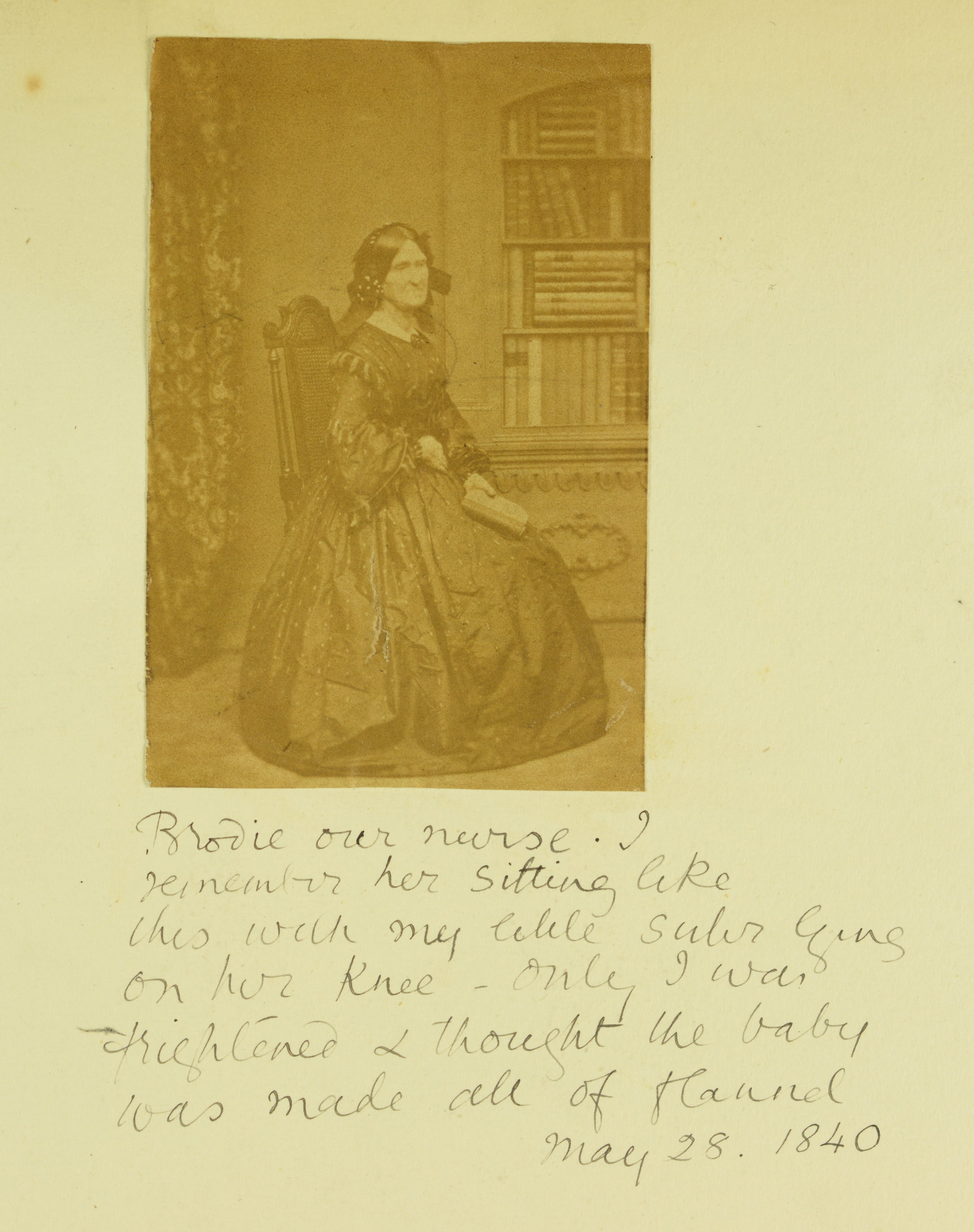

Photograph of Brodie, the childhood nurse of Annie and Minnie Thackeray (c.1840s) Eton College Library [MS 430/01/05/01]

Described by William Makepeace Thackeray as ‘the best nurse in the world’, Brodie was a loyal and constant presence in the otherwise unsettled lives of his daughters. This photograph (and others in this exhibition) is reproduced from an album compiled by Annie in later life, now part of the collection in College Library.

William Makepeace Thackeray, Watercolour of Annie and Isabella Thackeray (c.1838) [private collection]

William Makepeace Thackeray had first pursued art as a way to support himself, and continued to draw after he turned to writing. He produced a number of sketches and paintings of his daughters as well as the line illustrations to accompany his most famous novel, Vanity Fair. This watercolour by Thackeray is a rare image of Annie with her mother Isabella.

Photograph of Major and Mrs Carmichael-Smyth (n.d.) Eton College Library [MS 430/02/31]

Historians have not been kind to Anne Carmichael-Smyth, portraying her as a strict, formidable, and overbearing woman, but this one-sided view ignores the energy and intelligence of a person whose granddaughters recalled her ‘kindness of heart’. Her second husband Major Carmichael-Smyth, or ‘GP’ as the Thackeray girls called him, was a loving, ‘dear’ grandfather to both.

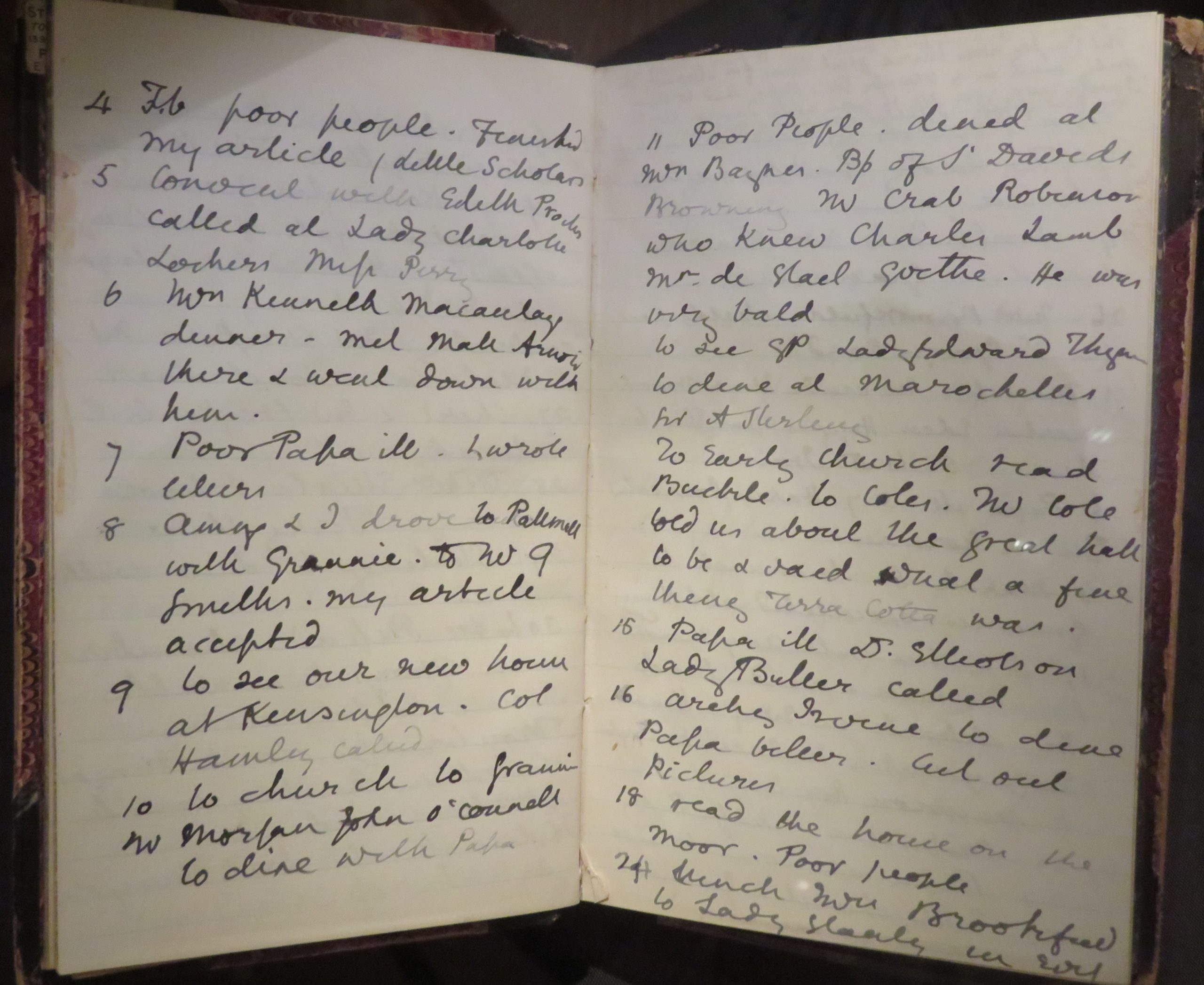

Anne Thackeray Ritchie, manuscript journal, vol. 1, 1859-1862 (entry dated 8 February 1861) Eton College Library [MS 430/02/20(i)]

This journal was copied and edited by Annie from her original diary in later life. Years after the event, the moment of hearing she was to be a published writer retained its importance for Annie, who transcribed her original entry on how she ‘drove to Pall Mall with Grannie. To Mr G Smiths. My article accepted’. The original diaries no longer survive.

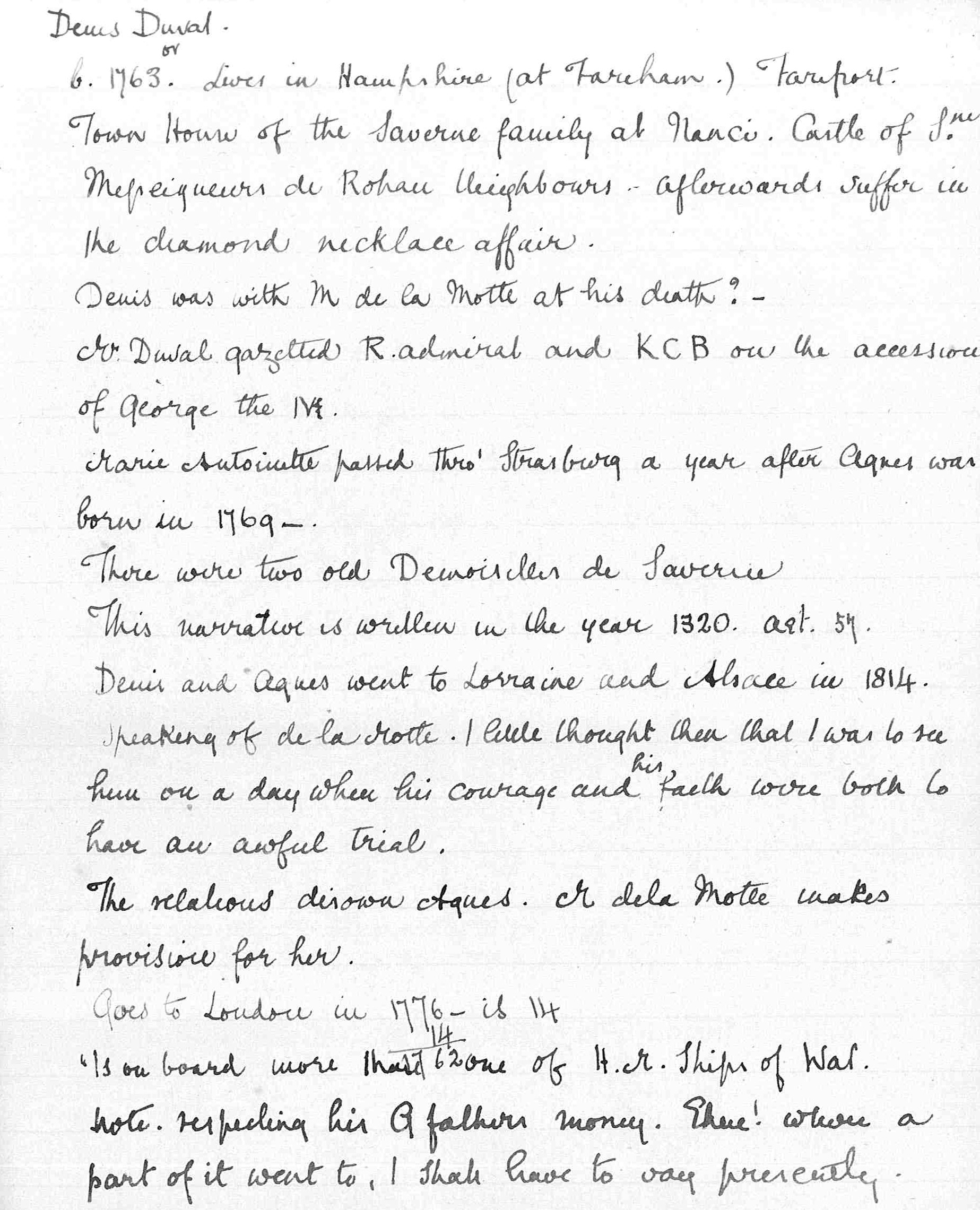

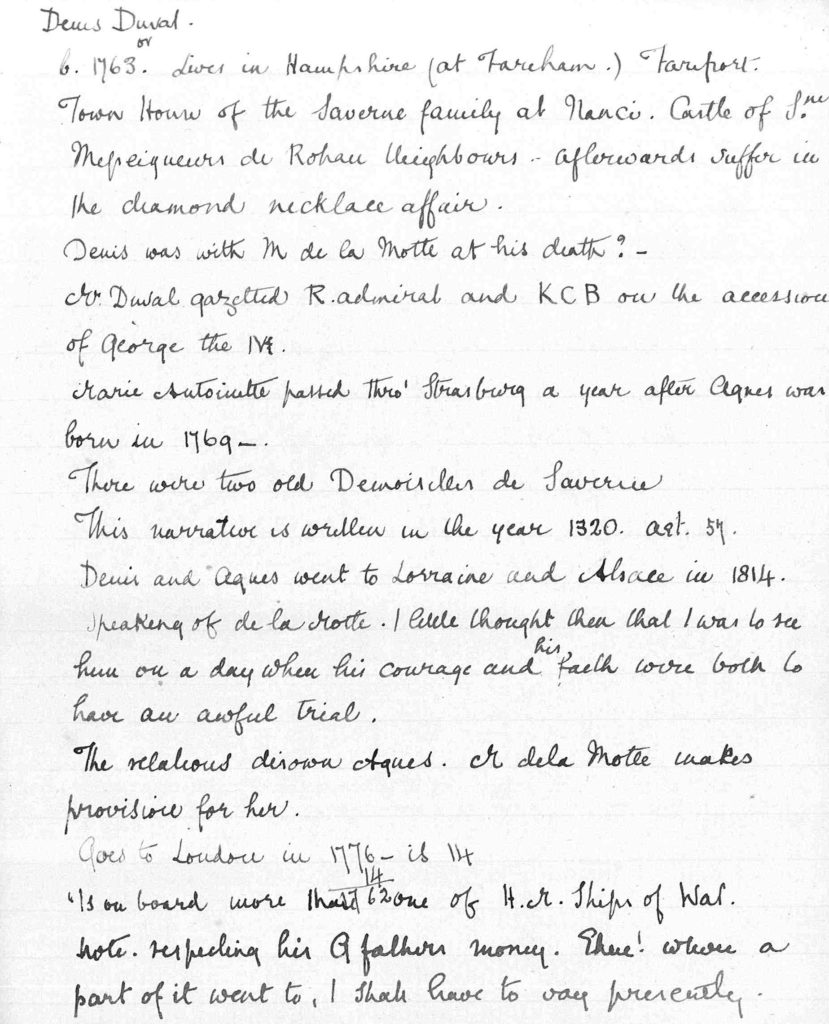

Manuscript notes for William Makepeace Thackeray, Denis Duval, in Anne Thackeray’s hand (c.1864) Eton College Library [MS 430/01/01/11]

Thackeray’s last novel, left unfinished at his death, was published in The Cornhill Magazine from March to June 1864, concluding with a ‘Note from the Editor’ written by his daughter to complete the story. Dated July 1863, this notebook contains Annie’s notes on how she believed her father intended the novel to end.

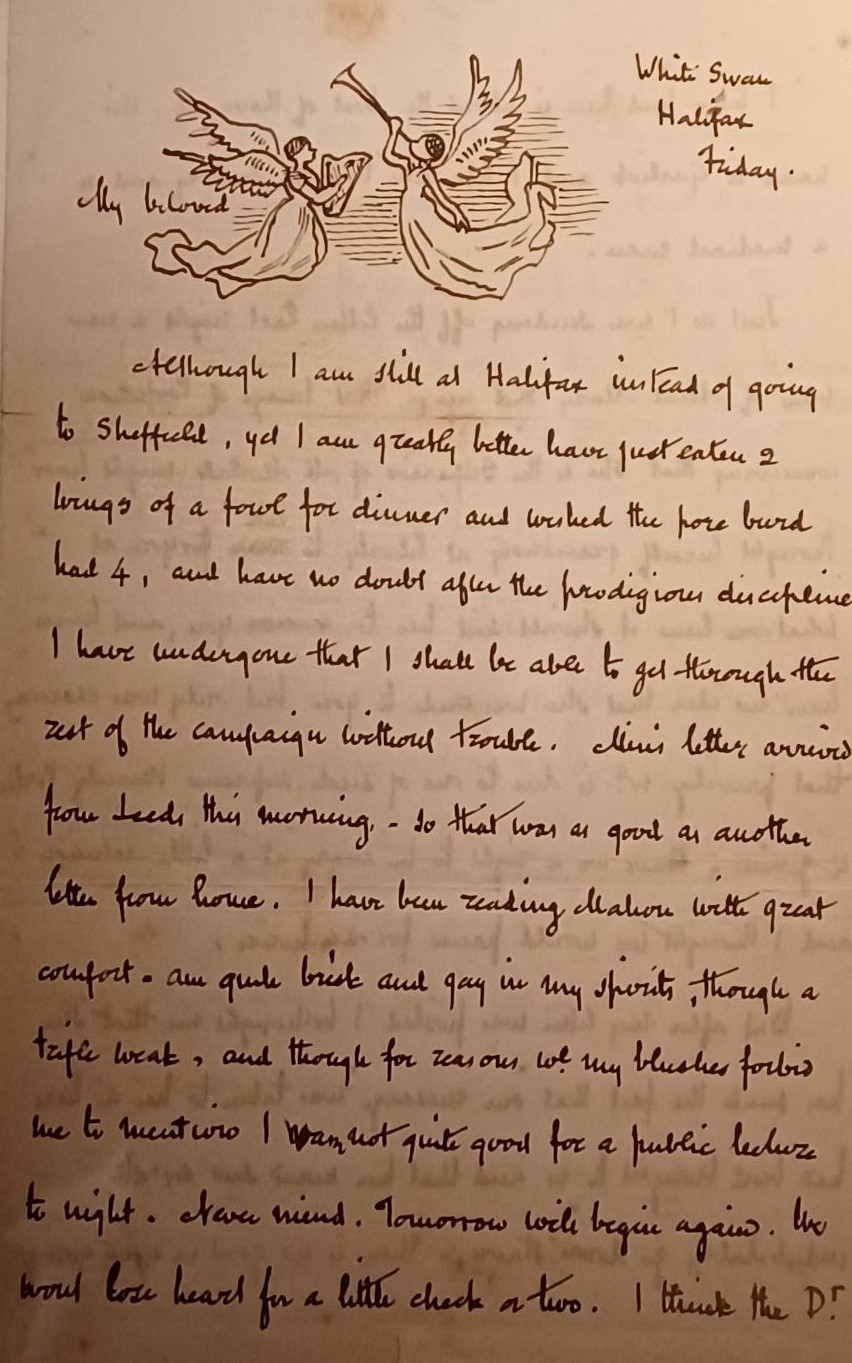

Letter from William Makepeace Thackeray to his daughters (13 February 1857) Eton College Library [private collection]

William Makepeace Thackeray spent years away from his young daughters, but he wrote to them regularly, and his letters often included humorous sketches. This letter includes a drawing of angels, which represented Annie and Minnie.

I would rather make my name than inherit it

William Makepeace Thackeray

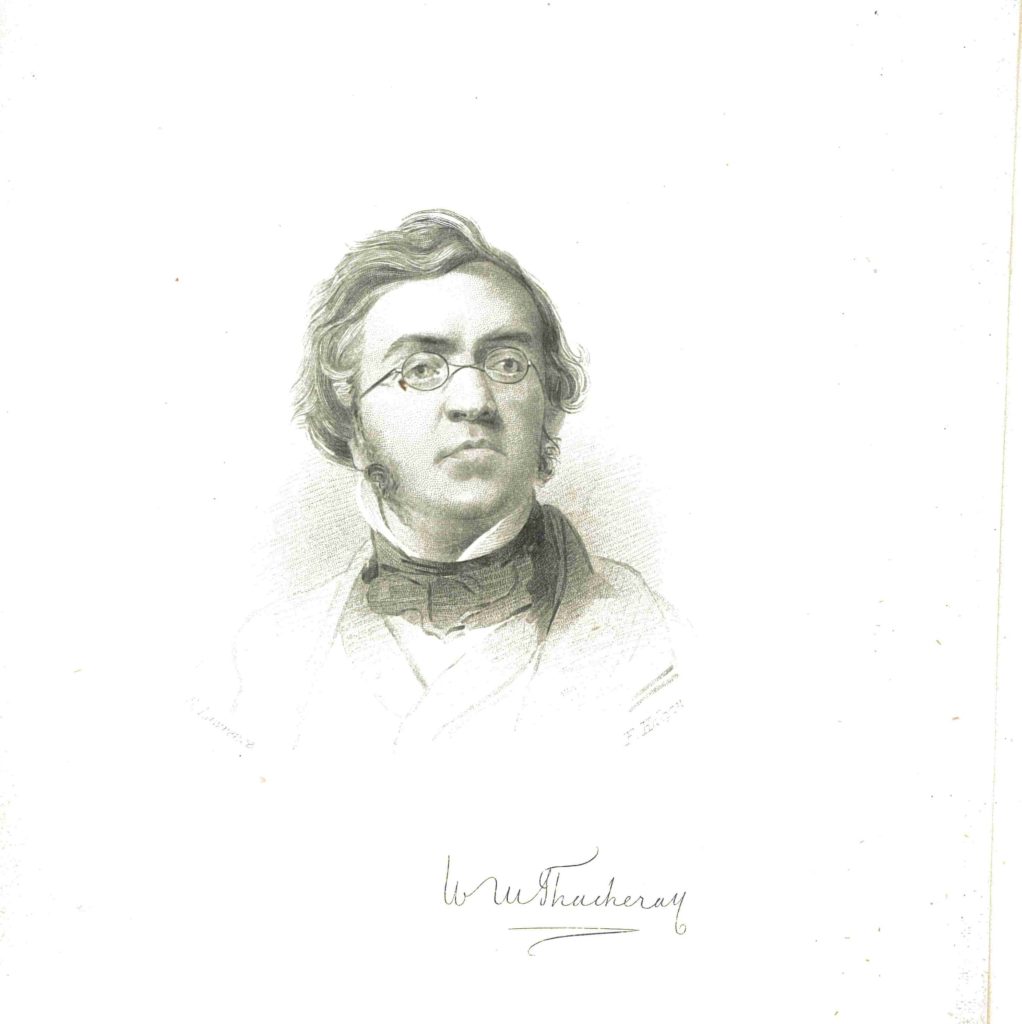

William Makepeace Thackeray was born on 18 July 1811 in Calcutta, India. When his father died in 1816, his widow Anne sent their son to England for his schooling, while she remained in India, marrying her first love Major Henry Carmichael-Smyth. The couple returned to England in 1818, before finally settling in Paris

It took until the 1840s for Thackeray to make a living from his writings, but once established, he was considered second only to Dickens.

Anne Thackeray owed more to her father than a literary inheritance. Her unconventional upbringing impacted the rest of her life, and her experiences took her from a young girl to a young writer, mature beyond her years.

I shall be much surprised if you do not carry on into the next generation the fame of the name which you bear

Letter from James Froude (editor of Fraser’s Magazine) to Anne Thackeray, 24 February[?] 1867

In 1837, the Thackeray’s celebrated the birth of a daughter Anne (Annie), followed a year later by her sister Jane. The loss of Jane at just eight months from a chest infection affected both parents deeply.

After the birth of their third daughter, Harriet Marian (always known as Minnie), Isabella experienced serve post-natal depression. By the end of 1840, Thackeray decided that Isabella required constant professional care at residential clinics.

…from the age of twenty-two [Thackeray] supported himself and kept a family on what he earned by writing for newspapers and magazines

Anne Thackeray Ritchie, quoted from The Works of William Makepeace Thackeray, 1910

What is to prevent women from studying…& making it a profession

Anne Carmichael-Smyth to Anne Thackeray Ritchie, 23 April 1852

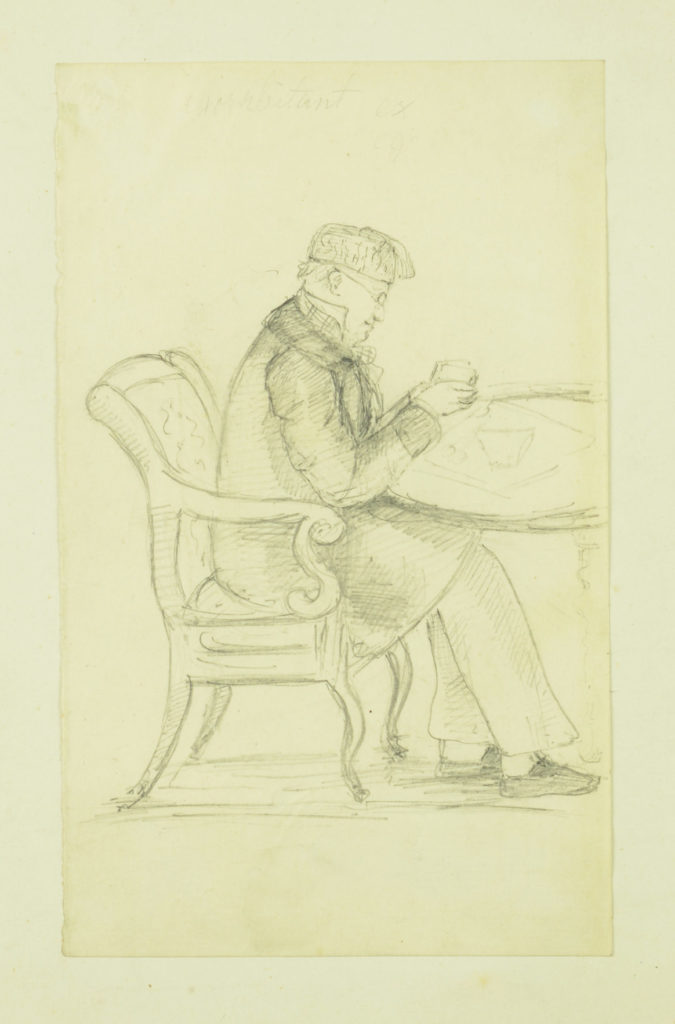

‘Our dear old grandfather did his best to cheer us all…after we had parted from my father’

Anne Thackeray Ritchie, Chapters from Some Memoirs (London: Macmillan, 1894)

Image: Sketch of Henry Carmichael-Smyth, by Anne Thackeray, (n.d.) Eton College Library MS 430/02/30

Anne Thackeray’s early literary ventures

By 1846 William Makepeace Thackeray was a well-established author and, feeling better able to provide for his growing daughters, brought them back to England to live with him in Kensington.

Annie gradually became her father’s amanuensis, and began writing short peices herself and Thackeray admired his daughter’s intellect.

the last line written by William Makepeace Thackeray. The story breaks off as his life ended- full of vigour, and blooming with new promise

William Makepeace Thackeray, Denis Duval (London: Smith, Elder & Co., [186–]) [Id5.5.19]

Manuscript notes for William Makepeace Thackeray, Denis Duval in Anne Thackeray’s hand Eton College Library

MS/430/01/01/11