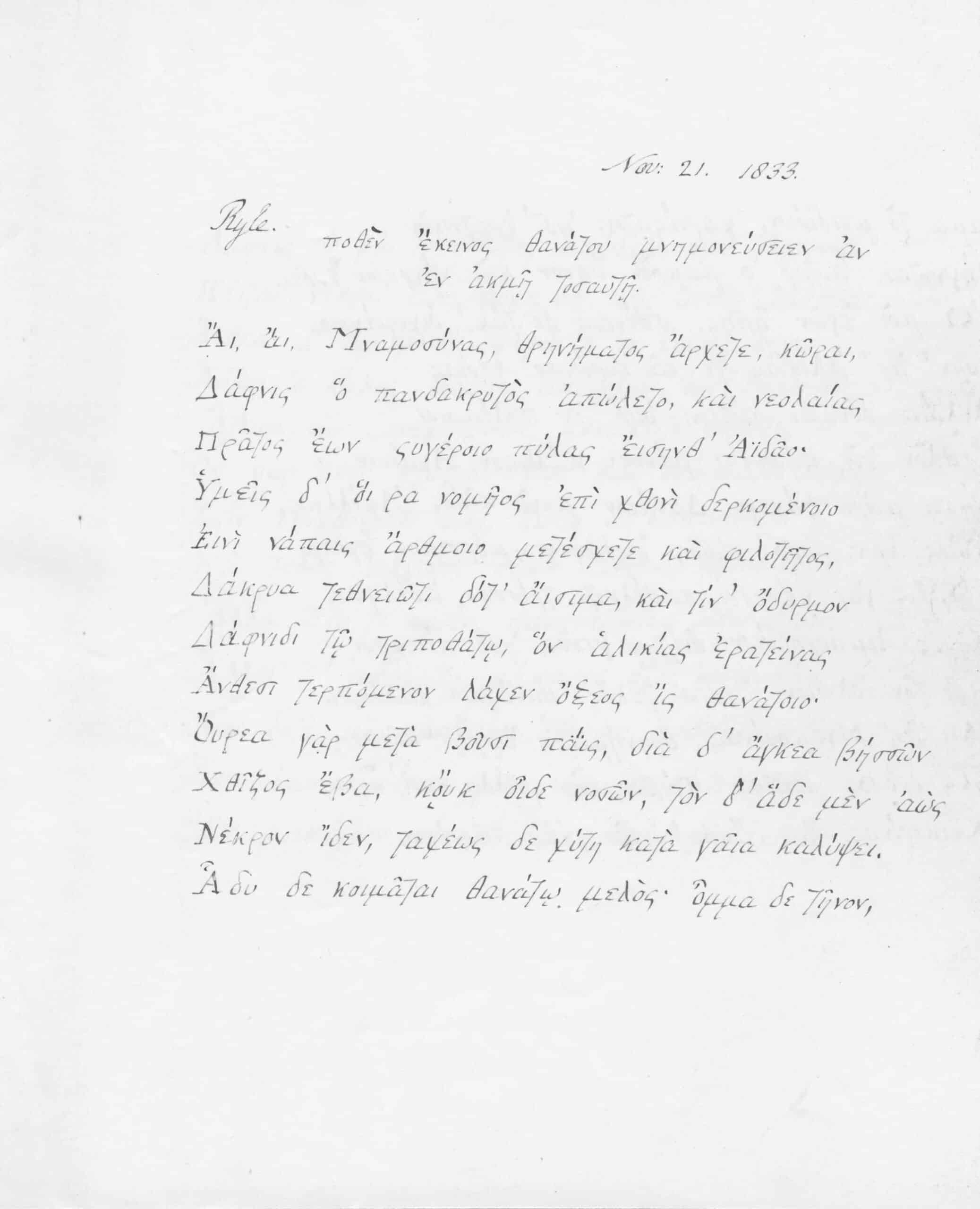

When Henry VI established Eton College in 1440, he intended it as a place for “poor and indigent scholars to learn grammar”. The boys would be tutored in Latin with an emphasis on writing verses. Eleanor Hoare, College Archivist, is currently cataloguing these archives and explores the background of Musae Etonenses:

Skill in the writing of Latin and Greek verses became a key Etonian accomplishment. Latin verse writing is first mentioned in 1479 in one of the Paston letters, and by the sixteenth century there were some very competent verses produced by Etonians. In the eighteenth century it had become a highly developed art; verses (and prose too) were not merely translations from English originals but free compositions, often on abstract themes. Later, in the nineteenth century, the translation of verses from English into Latin became standard. Work that was considered of an exceptionally high standard would be sent to the Head Master for his attention, the origin of today’s “sent-up for goods”. If he deemed the work to be of particularly outstanding quality, he would grant the whole school a day off – known as sent-up for play.

Housed in the College Archives is a rich and varied collection of these verses, which are currently being catalogued. This collection includes not only the work sent-up for good or play to the Head Master but also various verse-hoards made by boys and collections of their pupils’ verses made by tutors. The collection includes pieces by both well-known Old Etonians, such as Gladstone and Canning, as well as those who did not enter the public sphere.

These verses, largely written in the boy’s own hand, give an insight to the teaching methods, curriculum and quality of teaching in the 18th and 19th centuries. The decision of the individual tutor or boy to keep certain verses written by specific boys suggests that those writers or pieces were particularly important to him, giving information beyond the work itself into friendship groups and personal taste.