Exploring early modern innovations from the sundial to the slide rule.

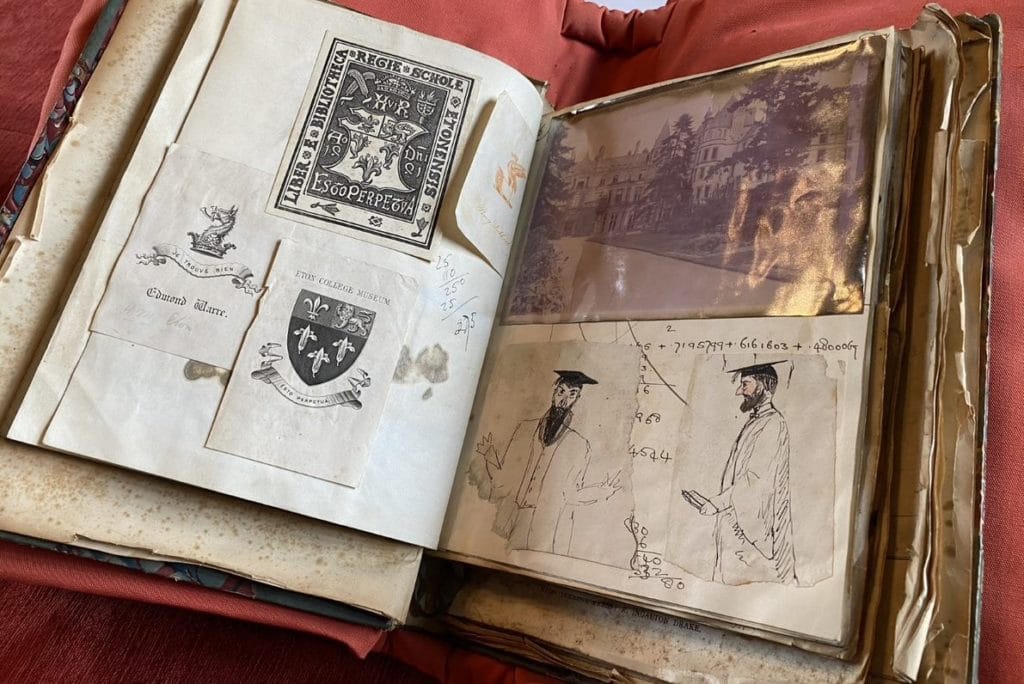

William Oughtred was born in 1574 and educated at Eton College, where his father was a Master. At the age of seventeen, he was admitted a scholar to King’s College Cambridge, becoming a Fellow in 1595 until 1603. Like so many of his university peers, Oughtred became a clergyman, and so remained until his death at the age of 86. But although preaching was Oughtred’s profession, mathematics was his true passion—John Aubrey recalled a man whose “head was always working”, drawing “lines and diagrams in the dust”.[1]

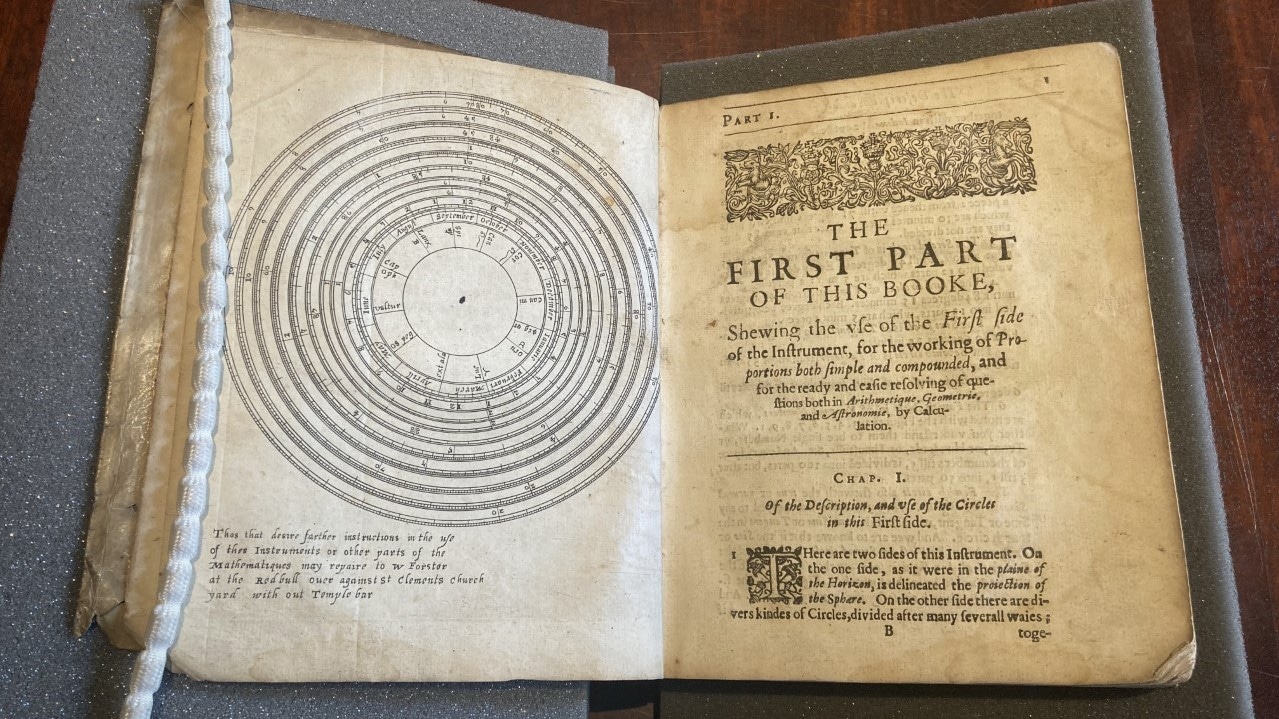

ABOVE: Engraved representation of William Oughtred’s multi-functional horizontal dial. Note the welcoming instruction below the illustration to ‘those that desire further instructions’. [ECL Ib1.1.51(02)]

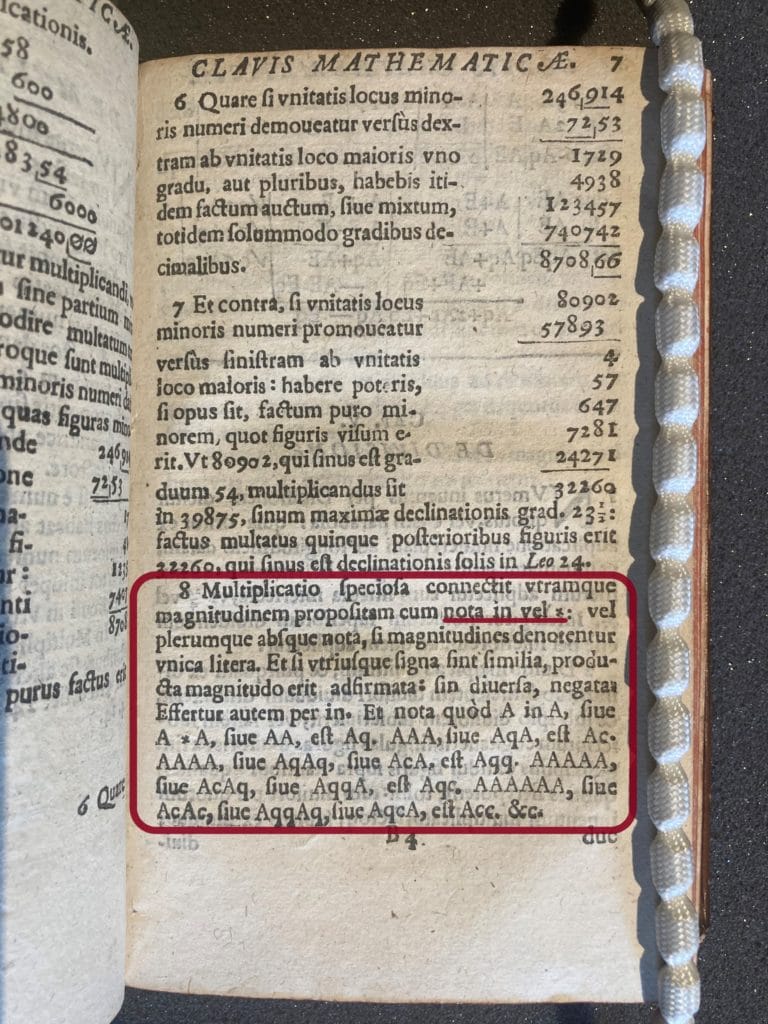

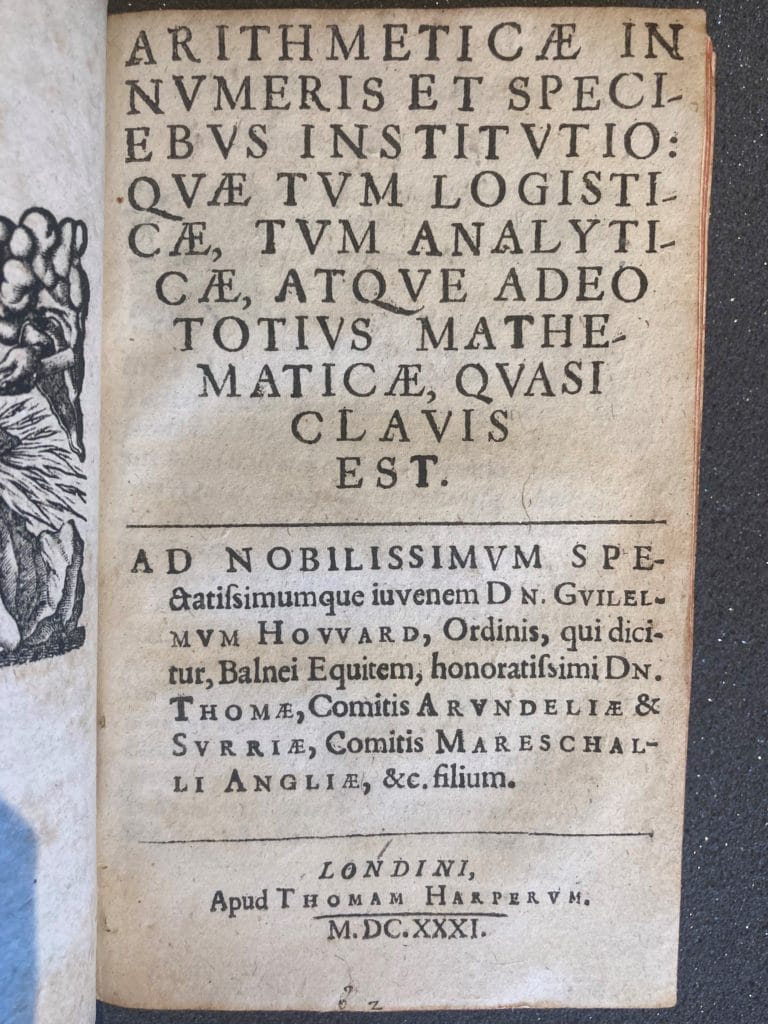

Among Oughtred’s most famous innovations is the slide rule, an analogue computer superseded only by the arrival of electronic calculators in the 1970s! Another innovation, nowadays so ubiquitous that we barely think about it, is the symbol × for multiplication. In 1618, this strange new sign appeared in an unsigned appendix (now attributed to Oughtred) to an edition of John Napier’s landmark work on logarithms, the Mirifici logarithmorum canonis constructio. In 1631, the humble × finally took centre stage—as printed here in the first edition of Oughtred’s Clavis Mathematicae or ‘Key to the Mathematics’:

ABOVE: A familiar symbol: Oughtred argued that a simpler mathematics, based in symbols rather than words, was of the most benefit to the student. [William Oughtred, Clavis Mathematicae, London, 1631. ECL Gb.7.25(02)]

It is noteworthy that Oughtred was nearly 60 years old when the Clavis Mathematicae was first published, though no doubt the substance of the work had been worked out many decades before, scribbled in his private notes. Fascinatingly, this lifelong interest in mathematics which led to so many ground-breaking discoveries and inventions was, in essence, an amateur obsession. The young William learned basic numeracy from his father and arrived at Cambridge infused—to use his own words—with “the love and study of those Arts”.[2] With his passion for “inciting, assisting, and instructing others”, Oughtred gained renown as a tutor despite living a fairly private life, and prominent figures such as the Earl of Arundel soon sought the services of “the most famous Mathematician of all Europe”.[3] Unsurprisingly, Oughtred’s preaching duties took somewhat of a back seat: contemporary accounts describe how the clergyman would study mathematics through the night, even having an inkwell attached to his bed-post in case of nocturnal epiphanies! And yet he did not seek recognition as a ‘professional’ mathematician—and seemingly had to be coaxed into publishing his manuscripts.

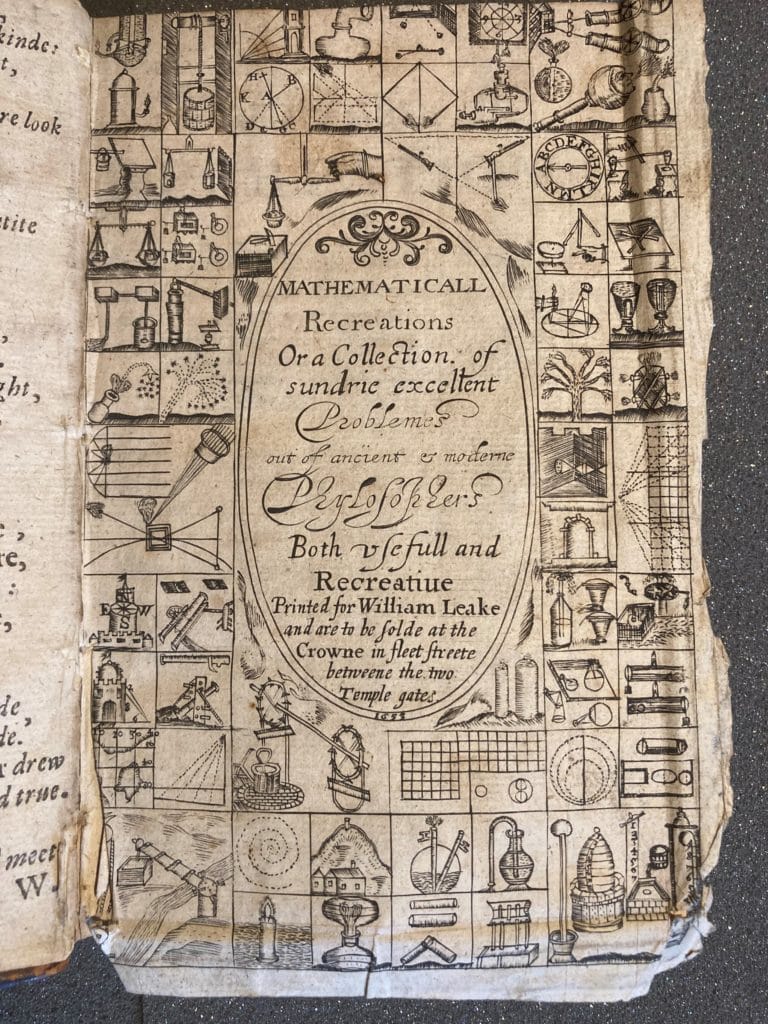

LEFT: Title-page of Oughtred’s first publication. Perhaps reflecting modesty, his name is not printed here. [William Oughtred, Clavis Mathematicae, London, 1631, ECL Gb.7.25(02)]. RIGHT: Oughtred contributed guides for two inventions to this popular work of mathematical puzzles and paradoxes. [Francis Malthus (translator), Mathematicall Recreations, London, 1653. ECL Ib1.2.32].

400 years later, Oughtred’s ideas greatly influence how we learn and teach mathematics, and even how we write it. College Library holds many examples of Oughtred’s works, including posthumous publications reflecting the popularity of his ideas; interestingly, these later publications often refer to ‘Guilelmi Oughtred Aetonensis’ (‘William Oughtred of Eton’) despite the relatively short time he spent at the school. Nonetheless—from advanced sundials to the abbreviations ‘cos’ and ‘sin’, the history of mathematics owes much to the clergyman whose head was full of numbers.

A selection of items from this blog will be on display in College Library from June to October 2022 alongside many more treasures from the Library and Archives.

REFERENCES

[1] Powell, Anthony (ed.), Brief Lives and Other Selected Writings by John Aubrey (London: The Cresset Press, 1949), pp. 139-145

[2] To the English gentrie, and all others studious of the mathematicks which shall bee readers hereof. The just apologie of Wil: Oughtred, against the slaunderous insimulations of Richard Delamain (London: A. Mathewes, 1634?)

[3] Cajori, Florian, William Oughtred : a great seventeenth-century teacher of mathematics (Chicago, London: The Open Court Publishing Co., 1916)