The Expedition of the Pacific Ocean on the HMS Endeavour Voyage 1768-1771

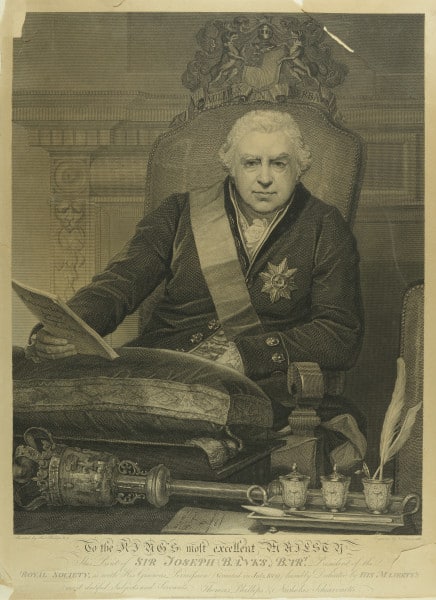

Sir Joseph Banks (1743-1820) compiled a small team of people to help him collect and beautifully record botanical samples from around the world under the explorer Captain James Cook on his ship, the Endeavour.

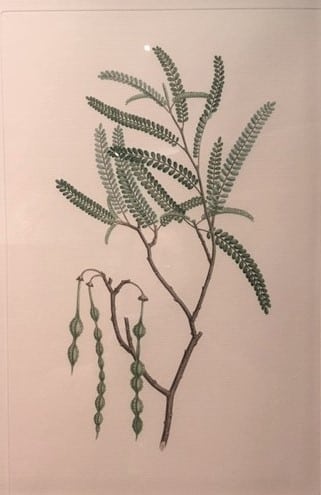

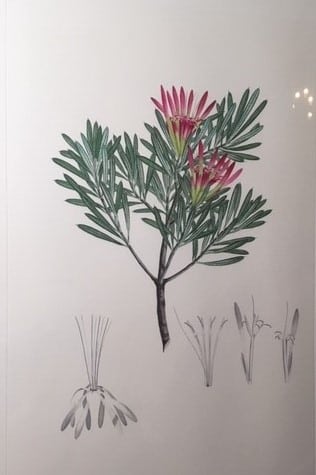

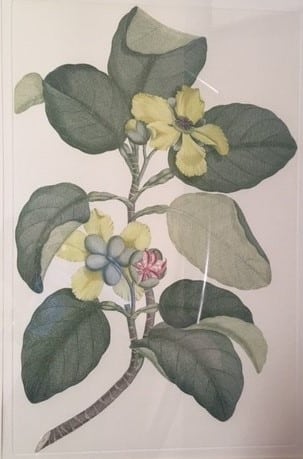

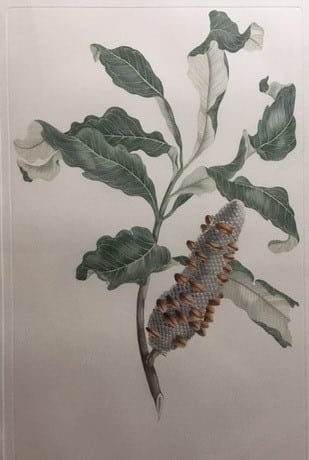

The Florilegium is a collection of New World plants by Joseph Banks, Daniel Solander and Naturalist draughtsman Sydney Parkinson. Banks began a lifelong creative partnership with Solander, a Swedish naturalist. When the ship was docked south of now Sydney, from April 28th-May 5th 1770, the men yielded so many previously unrecorded specimens to Banks’s botanical collection that Captain Cook named the area, ‘Botany Bay’. [1] Together they travelled to Australia, New Zealand, the Society Islands (Tahiti, Moorea, Raiatea, Bora Bora and Huahine) Tierra del Fuego, Brazil, Java and Madeira collecting and recording plants in the period of Enlightenment and its contribution to science and arguably to fine art.

Sydney Parkinson drew from nature watercolours and sketches of the plants they collected, which were made into engravings. Four other artists were also employed by Banks to work from dried specimens and sketches once they got back to England. Out of their party of nine on the voyage, only Banks, Solander and his two servants survived of ‘ship-borne illness’. Upon their return to England, the men became heroes of the London scientific community.

Banks brought thousands of new species to the attention of the science of the Western World, including acacia, eucalyptus and banksia – a genus named in his honour. He completed a 200,000-word journal and collected 30,000 plant specimens; half would be new to science. Parkinson completed 269 botanical watercolours and 673 unfinished sketches before he died on the return journey from South Africa at age, just 25.

When what remained of Bank’s team and crew of the Endeavour, returned to England, he apparently put aside £10,000 to publish 14 volumes. A collection of 942 plant illustrations, 753 would eventually be engraved for printing. The project never came to fruition, sadly because of the deaths of his contributing team, as well as financial losses during the American War of Independence.

As Mel Gooding explains in his book ‘Banks’ Florilegium’, the illustrations were intended primarily as a contribution to science, “the initiation of Australian botany”[2]. But to the modern reader, the Florilegium is more of a work of art. Gooding writes that it is

“a work of outstanding graphic achievement and a radiant revelation of natural beauty in its infinite variety and particularity”.

The Natural History Museum at Eton College, boasts a beautiful collection of Banks prints from this period. The plates were printed a la poupee, a colour printing process. The printer works each colour into a single copper plate with a rolled-up cloth dolly. To be as accurate as possible with producing the watercolours, up to 17 colours were used for each plate.

More about Banks:

Joseph Banks, engraving by Niccolo Schiavonetti, after Thomas Phillips, RA.

http://collections.etoncollege.com/object-fda-e-1588-2014

1766 – To Labrador and Newfoundland on the Niger.

From his early years, Joseph Banks was surrounded by lush borders of undrained land that attracted a large variety of waterfowl at Revesby Abby, his family home in Lincolnshire. Banks was also privy to a relative’s home; Burghley House, Northamptonshire, a well-preserved landscape of climatized exotic trees and shrubs. Naturally, during Banks’s education at Eton College, he was driven to study natural history in favour of the classics.

He continued his education at Oxford, where he began to build an herbarium; a collection of plants stored and catalogued, for study by professionals. This included a Geum macrophyllum, a plant collected from Labrador in 1763 by Moravian Missionaries, along with other plants from this region. Their headquarters were close to Banks’s home in London. It was also from them that piqued his interest in Labrador and Greenland.

Upon his father’s death in 1761, William Banks’s estate was left to his son to inherit when he turned the appropriate age of 21. This allowed Banks to financially pursue his passion for the exploration of the natural sciences, becoming a local squire and magistrate in the years before his expedition.

In 1766, Joseph Banks along with a school friend Constantine John Fipps, climbed aboard the HMS Niger under Sir Thomas Adams. On May 11th, they landed at Chateau Bay, Labrador. In the surrounding waters, they encountered a penguin like bird, later identified as the Great Auk or Pingunus impennis. This creature would be declared extinct 78 years later, due to over hunting for food, feathers and oil. They arrived in the breeding and nesting season, taking notes on the Black-capped Chick-a-dee, much like a British Coal Tit. They saw the Robin-Redbreast, roughly the size of a Black bird and a variety of Warblers. In the harsher weather when creatures hunkered down, Banks would stick to the harbour and make geographical notes and search for marine life. Locals caught up in Banks’s interests were generous in sharing specimens and regaling their own almanacs. On June 6th, he collected plants such as the ‘Little Dwarf Honeysuckle’ (Cornus herbacea) and a beautiful sample of ‘Medalar’ (Amelanchier).

On October 10th, 1766, the Niger arrived at St. John’s, Newfoundland. Banks and his company were relieved to get back to society which they felt they had been deprived, stating, “As everything here smells of fish so, you cannot get anything that does not taste of it”. On October 25th, Governor Palliser gave a party to recognise the fifth anniversary of the coronation of King George III. Gifted men had attended this event: John Cartwright had a career in the Navy along with his brother George, who became a collector of plants and animals for Banks during the trip to Labrador. Once Banks and his company returned to England, he set to work sorting through his findings to classify and record with help from Daniel Carl Solander, a Swedish Naturalist.

Linnean Taxonemy is a paper indispensable for Nomenclature, the system of classifying names for things. Banks made his name by publishing the first Linnean, based on the fauna and flora that he studied in the eastern seaboard of the Canadian Provinces of Labrador and Newfoundland. He was also elected a Fellow to the Royal Society for his contributions to the natural sciences where he remained a member for 40 years.

By Val Young, Gallery Steward

If you are interested in Joseph Banks, his life, work, and the Florilegium, look out for the exhibition To Botany Bay and Back: The Worldwide Web of Sir Joseph Banks.

References

[1] State Library- New South Wales, Australia

[2] Mel Gooding, Joseph Banks’ Florilegium: Botanical Treasures from Cook’s First Voyage, 2019

Lotzof, K., Joseph Banks: Scientist, Explorer and Botanist, London Natural History Museum, April 1, 2020

Lysaght, A.M., Banks, Sir Joseph, University of Toronto, 1983, April 1, 2020