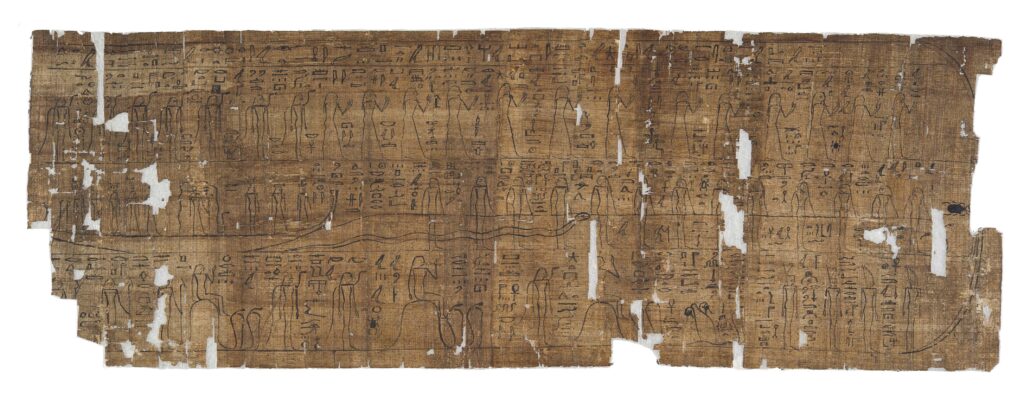

One of the star items in Ancient Beings, an exhibition of 32 Ancient Egyptian artefacts recently returned from loan and displayed in the Tower Gallery, is this fragment of the Book of Amduat.

The Book of Amduat is an Ancient Egyptian funerary text and was intended to be a guidebook for the deceased, to assist them on their journey to the afterlife. The text is written in hieroglyphs, a system of writing that was reserved mainly for use in religious and funerary contexts.

Originally produced on the walls of royal burial chambers, the Book of Amduat was called the ‘Writing of the Hidden Chamber’. In the Third Intermediate Period such funerary texts came to be used by other notables outside the royal family, and were reproduced on papyri and placed between the legs of the mummy. In these papyri, only sections from the last four hours of the Amduat were included. Where the earlier hours were more connected to royal funerary rituals, the last four hours focus on the progress towards the morning rebirth of the Sun god (and thereby also of the deceased who was buried with the papyrus).

The text is divided into twelve parts which represent Re, the god of the sun, as he travels through the netherworld over twelve hours. Re (or Ra) travels on his barque (boat), through the Duat (underworld), a journey which the Ancient Egyptians believed that they would also be required to undertake on death. During this journey Re unites with Osiris, god of the dead, and is reborn for each new day.

It was believed that when a person died, an aspect of their spirit called ba would make this journey to the judgment halls of Osiris. The Amduat assists the dead individual by supplying the names of the gods, demons and monsters that they were likely to encounter, so that they could use these names either to gain their help or to get past them. In overcoming the perils and obstacles placed in their way, they could successfully make their way to the judgment hall, where their heart would be weighed against the feather of maat (or ma’at). Maat was the order of the universe; the Goddess Maat was the daughter of Re and was the personification of this cosmic order, in addition to truth and justice. If found worthy, the deceased would be allowed to enter the ranks of the blessed dead. If unworthy, however, they would be consumed by a demon, the ‘devourer of souls.’

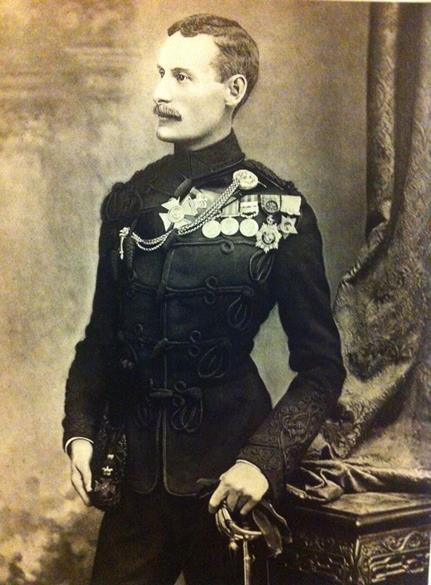

The Eton fragment of the Book of Amduat was acquired with other antiquities by Major William Joseph Myers (1858-1899) between 1885 and 1898 during his military placements in Egypt. Following his return to Britain Myers became Adjutant at Eton College and bequeathed his collection of antiquities, including this papyrus fragment, to the school. It is dated to the Third Intermediate Period and is believed to have belonged to a priest of Amun whose name has not been preserved.

This fragment pulls together sections of the eleventh and twelfth hours of the Amduat within the same time frame, supporting the belief that neither the full text nor an explicit order is necessary: it is the presence of the Amduat accompanying the deceased that is required to fulfil the magical role of guidebook to the deceased.

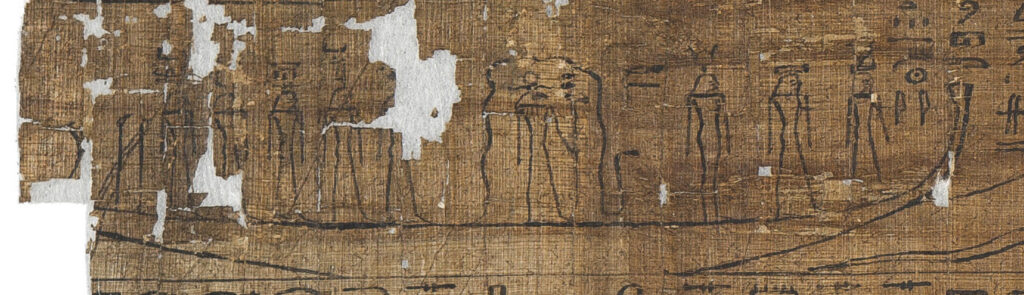

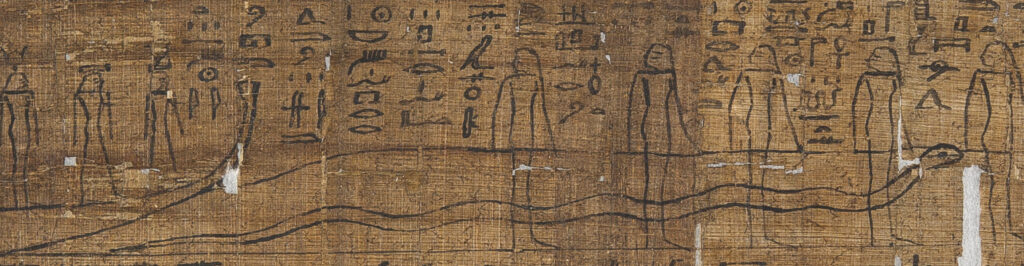

On the upper register of the fragment are seven goddesses with snakes on their shoulders, and ten gods, each identified by name. The middle register shows Re on his barque, with a number of deities including the snake god Mehen. The middle and lower registers also depict the deities who pull Re and his barque through the Duat.

These final hours illustrate the latter stages of the journey through the underworld where Re, now united with Osiris, undergoes rejuvenation and heads to the east to rise with the sun of the new day.

Mehen is a protective snake god, who coils around Re during his journey through the Duat, protecting him from the many evils in the underworld. He stands on the night barque, guiding Re’s passage through the Duat.

In the twelfth and final hour Osiris and Re separate, with Osiris remaining in the Duat while Re enters the day barque. Re now appears wearing the Uraeus (sun disc) as he is fully rejuvenated after his journey through the underworld. Re and his barque enter the gigantic serpent from the tail, and emerge from the mouth in order to start the new day.

The regenerated Re is also seen as the god Khepri, the god of the morning sun. Khepri is associated with the scarab beetle because the scarab roll their dung across the land in a way thought to symbolise the journey of the sun across the sky. Due to this, the scarab beetle was a symbol of regeneration in Ancient Egypt. In the Amduat, this connection is represented by the scarab with a sun disc (not preserved), pushing forward the horizon – possibly represented by the curved arc across the right-hand end of the papyrus.

References:

Gallagher, K. and Escolano-Podeva, M., Object record for ECM.1573, The Johns Hopkins Archaological Museum, 19th October 2016

Piccione, P., ‘Mehen, Mysteries, and Resurrection from the Coiled Serpent’, Journal of the American Research Center in Egypt, 1990, 27, 43-52

Swaney, M. and Moroney, M. (Eds.), Selections from the Eton College Myers Collection, The Johns Hopkins Archaeological Museum, April-August 2016

http://www.sofiatopia.org/maat/amduat.htm

By Rebecca Tessier, Museums Officer