“Some time ago I believe I had the pleasure of telling you a story …”

Before Long Leave, the school’s Head of English asked the College Collections to help put together an unusual lesson. In the run-up to Halloween, F-Block boys (Year 9) were invited to view some of the Collections’ spookiest materials in College Library, as inspiration to write their own ghost story. After reading a passage set in a fictionalised Eton from Susan Hill’s ghost novel The Mist in the Mirror, boys were led along the route described by the narrator to College Library’s eighteenth-century rooms, lined with tens of thousands of pre-modern books, where they found manuscripts, books, prints and natural history specimens to set the scene.

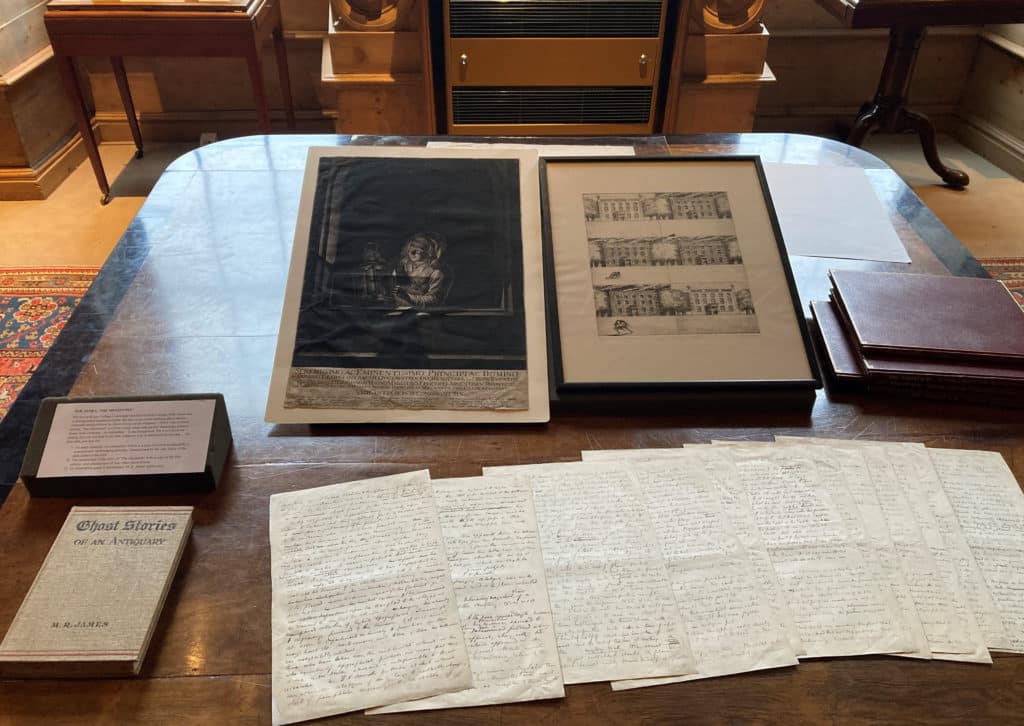

There they saw the original autograph manuscript of former Eton Provost and Librarian M.R. James’s well-known short story ‘The Mezzotint’, showing his revisions. James wrote this and other ghost stories to read aloud to his friends as a seasonal entertainment, and his tales often centre on uncanny manuscripts and artefacts—just the kind of thing the library is filled with. ’The Mezzotint’ tells of a museum curator who is sent a very disturbing nocturnal engraving which changes each time he looks at it, revealing a ghostly tale of murder and revenge. We accompanied the manuscript with an evocative example of a mezzotint and a modern etching illustrating the story from the Fine and Decorative Arts collection, and a first edition of James’s first collection, Ghost Stories of an Antiquary (1904).

M.R. James, autograph manuscript of ‘The Mezzotint’ (ECL MS 369, early 1900s) with a copy of the first edition, an early mezzotint (FDA-E.378-2010, Jan Thomas after Gerard Dou, Girl at a window placing a candle in a lantern, 1661) and an etching illustrating the story by an unidentified artist (FDA-E.1319-2014, produced in 1980).

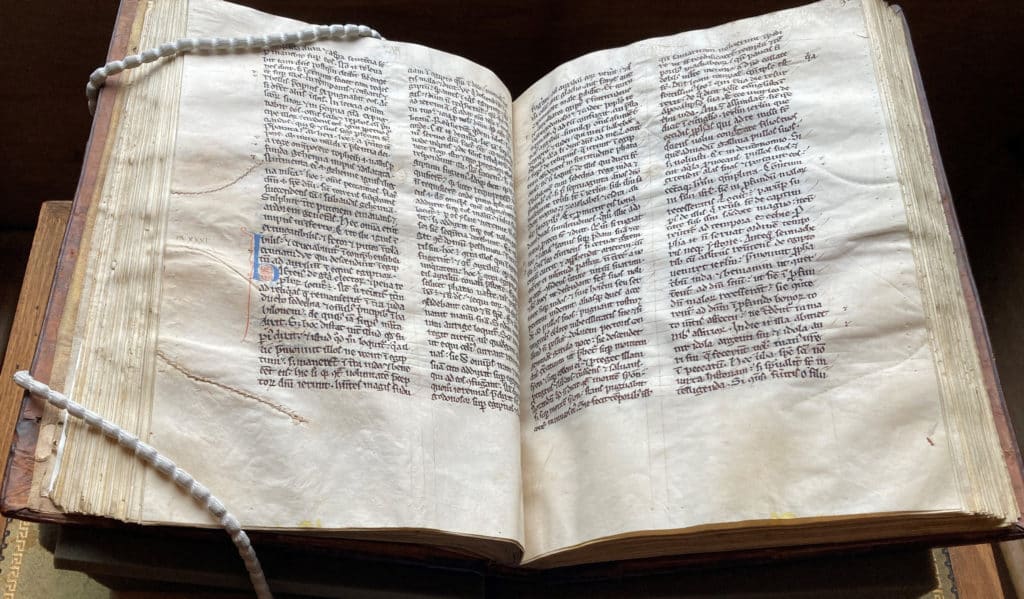

James was a keen antiquarian, so we chose some medieval manuscripts of the kind discovered by the narrators of his stories to add a light touch of eeriness. Many books produced in the Middle Ages were copied on animal skin rather than paper. Due to the nature of this material, it sometimes still bears visual reminders of the animal it once came from, such as blood capillaries or even faint shadows of bones – usually the vertebrae or hips of the animal. Furthermore, the process of preparing the skin to be a writing surface entailed stretching the skin to make it as thin as possible, meaning it often ripped into holes. We showed an example of stitches being used to remedy such imperfections, sewn as if wounds.

Haimo of Auxerre, Commentary on the Book of Isaiah (ECL MS 20, from England, 1150-1200)

Also on display were a death mask of the poet John Keats, a lock of hair clipped off the corpse of King Edward IV when his tomb was accidentally opened in 1789, and a disturbingly large specimen of a tarantula from the Eton Natural History Museum.

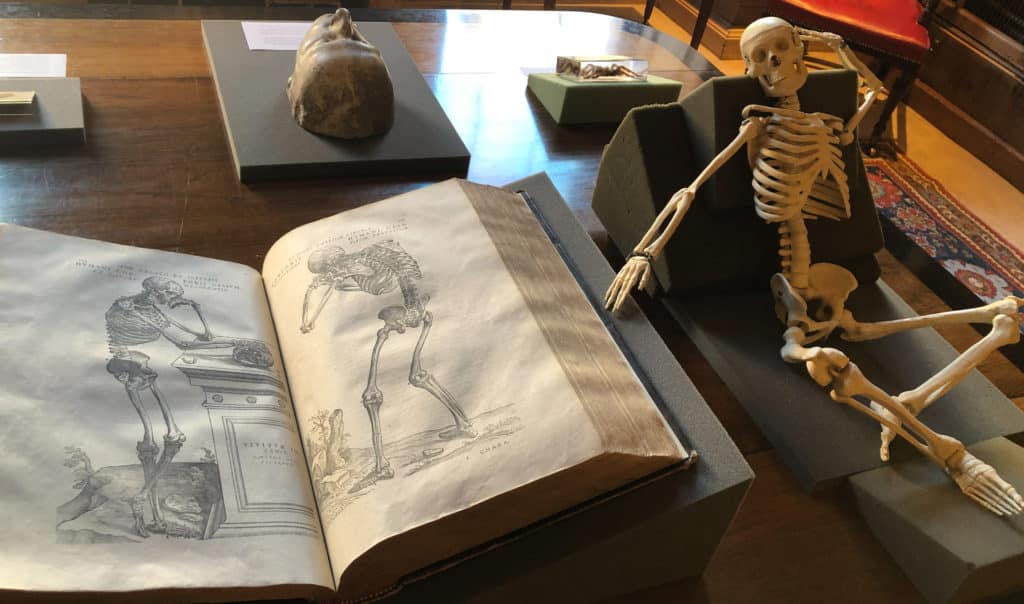

To top it all off, the boys were shown a copy of a key text in the history of medicine: Vesalius’ sixteenth-century manual of human anatomy, De Humani Corporis Fabrica Libri Septem, alongside a three-dimensional model. His work made him famous across Europe for providing a new model for the understanding of the human body, which had not existed since the work carried out by 3rd-century Greek physician Galen. The macabre illustrations, peeling away the skin and muscles to reveal the human skeleton, were an important source for artists as well as doctors and surgeons.

Andreas Vesalius, De Humani Corporis Fabrica Libri Septem (ECL Ga.1.09, Basel, 1555) … with friend!

We hope that between our collections and our colleagues in the English department, we have stimulated the boys’ creativity, and we look forward to reading some of their pieces when they are finished!