Walking through Eton College Library today, it’s easy to imagine the music that once echoed through its halls. For years, the Library’s music collection was scattered, but the recent cataloguing project has brought nearly 380 printed and manuscript scores together for the first time. What emerges is not just a list of titles, but a vivid human story: of pupils singing in Chapel, masters preparing lessons, and composers leaving their deepest thoughts in ink. These scores don’t just preserve music, they preserve memory.

The printed scores show us exactly how music circulated through the College community over centuries. Rather than a static list, they read like a map of the pieces actually studied and sung, music for the services at the Chapel, Romantic keyboard works for private study, and choral music that filled rehearsal rooms.

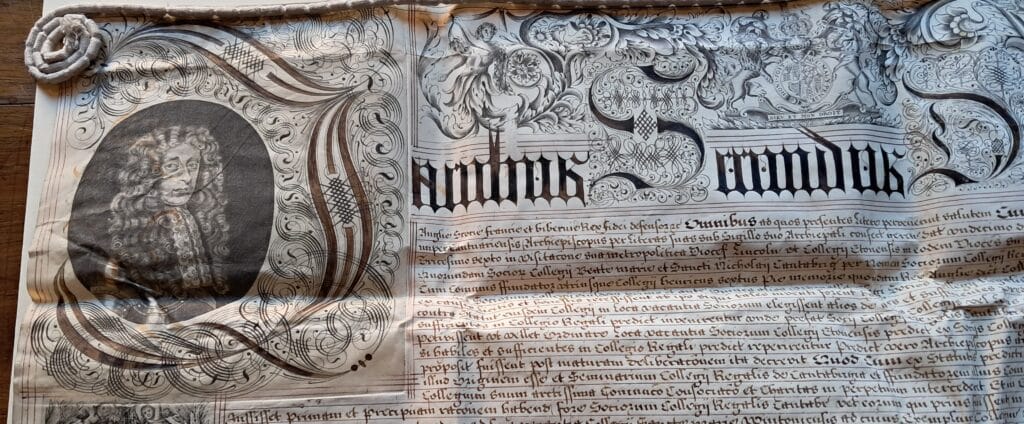

One of the most striking finds is Thomas Arne’s Musick in the Masque of Comus [Ibb5.5.01], an early engraved edition of the work that launched his career. As an Etonian, Arne set John Dalton’s adaptation of Milton’s Comus. Its title page exemplifies the shift to a commercial music economy, using imprint details to direct buyers to both music shops and Arne’s own lodgings. By clearly listing distribution channels and adding his signature for authenticity, Arne uses the page as a marketing tool to treat his work as a public commodity. This highlights the composer’s entrepreneurial role in establishing a new marketplace for printed music.

The collection also highlights how musicians used these works in practice. The high number of “composite volumes”, bound-together collections mixing composers and genres, reflects how musicians created practical, personal anthologies. These were the “playlists” of their day, showing what was actually performed and valued by pupils and masters. Some volumes include richly illustrated title pages that offer a vivid glimpse into the fashions and tastes of their time.

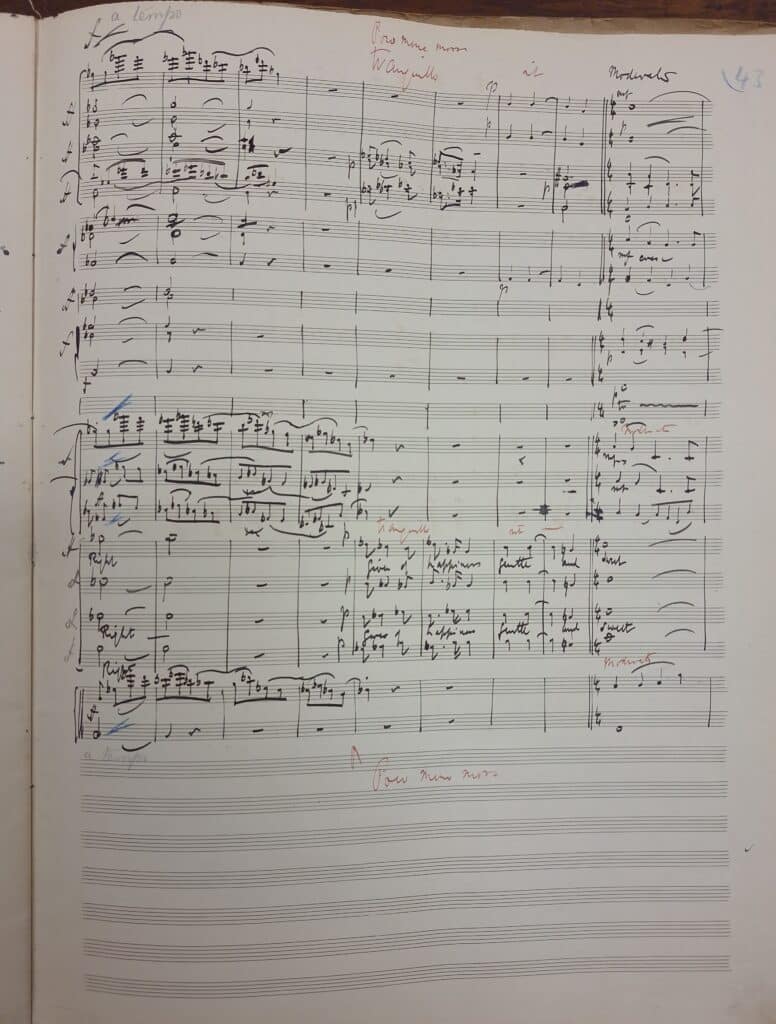

While printed scores show the finished product, our manuscript scores offer a view of creativity in motion. They show music while it was still being shaped: phrases crossed out, dynamics reconsidered, and ideas refined in the margins. We have catalogued numerous works where both the manuscript and printed edition are preserved, such as C. Hubert H. Parry’s Eton Memorial Ode [MS 357A], which is covered in corrections for publication. When these manuscripts are placed alongside the printed scores, it becomes possible to trace the music’s entire path from private creation to public performance.

Beyond the music itself, the catalogue includes letters that capture the voices and personalities of the composers. A striking example is a 1929 letter from Peter Warlock, written during the final year of his life, confirming his decision to adopt his pseudonym. Other items, such as an intriguing letter from Claude Debussy regarding his social and political views, tie Eton directly to the wider world of early twentieth-century music.

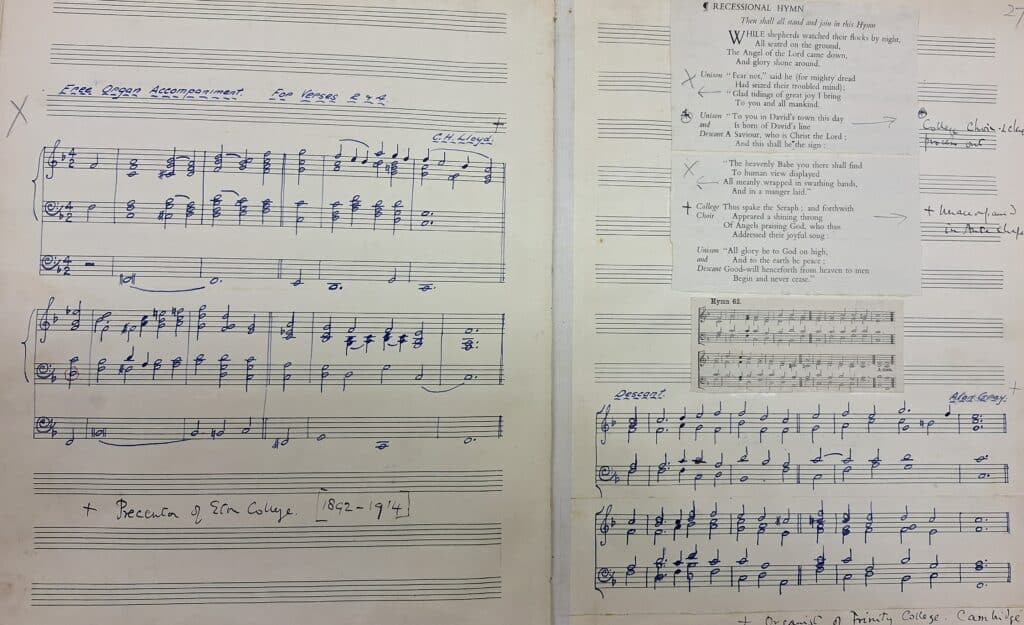

Finally, the collection reveals the quieter, day-to-day life of music at Eton through the scrapbooks of Henry G. Ley. These volumes are particularly evocative, filled with pasted-in score fragments, typed texts, and quick handwritten notes for Chapel services. They capture the College’s musical life mid-stride, showing tradition not as something fixed, but continually shaped by those who lived and worked with it.

The catalogue uncovers the active life of music at Eton. These scores were sung, corrected, shared, and loved. For the first time, the full breadth of this history is visible and accessible, opening the door not just to researchers and performers, but to anyone interested in how music moves through communities and across generations. Explore the catalogue and discover the stories behind the notes, it’s a journey through Eton’s musical past that still resonates today.

Alex Cuadrado, Project Cataloguer