The Eton Choirbook, a rare and lovely survival of early Tudor choral music, does not contain any Christmas carols. Carols were around in the years 1500 to 1504, when the choirbook was being made. They have their roots in the early middle ages, when Christmas music was either liturgical (the sequences of hymns assigned to the services for Christmas Eve, Christmas Day, Epiphany, and so on) or popular songs that formed part of secular traditions like wassailing. Some of them, like O Come all ye Faithful, Good King Wenceslas, and Good Christian Men, Rejoice, are still popular today.

But the music of our choirbook, Eton MS 178, is not specifically Christmassy. The hymns dedicated to the Virgin Mary that were copied into the choirbook were intended to be sung every single day. On the other hand, they are almost all dedicated to one of the most important figures in the Christmas story: Mary, the mother of God. The texts of the hymns in the Choirbook worship Mary in language very familiar to us in carols, particularly the carols that celebrate the annunciation to Mary by the angel Gabriel or that show Mary singing to Jesus in the manger, and carols for Advent which promise universal salvation through the miraculous birth of the infant Jesus.

The short hymn Nesciens mater, set by Walter Lambe, shows Mary as nursing mother and queen of heaven:

Nesciens mater virgo virum

peperit sine dolore

salvatorem saeculorum.

Ipsum regem angelorum

sola virgo lactabat,

ubere de caelo pleno.Knowing no man, the Virgin mother

bore, without pain,

the Saviour of the world.

Him, the king of angels,

only the Virgin suckled,

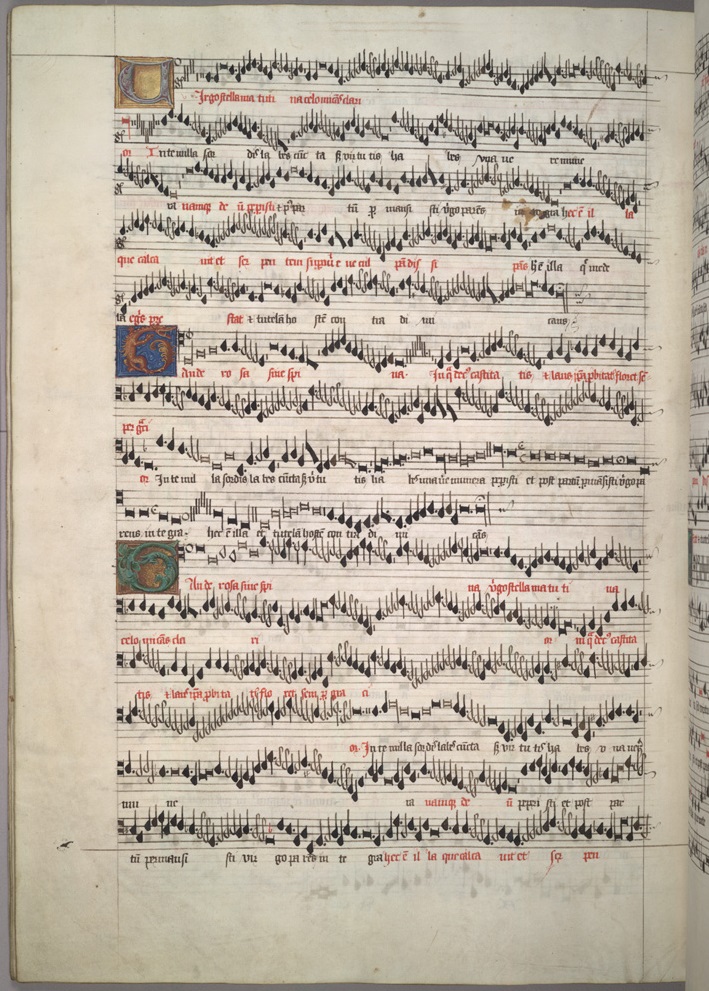

breasts filled by heaven.Nesciens Mater, set by Walter Lambe. Eton Choirbook, folios 87 verso-88

Listen on Spotify

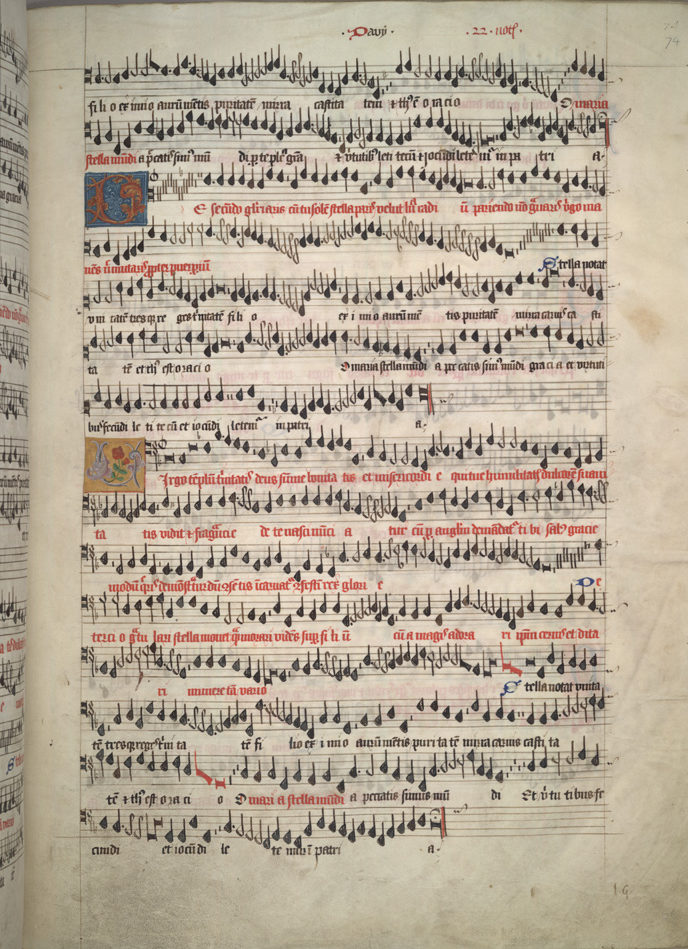

The text ‘Gaude rosa sine spina’ (set in the Eton Choirbook by Richard Fawkner) also adopts a trope common to medieval Advent carols:

Rejoice, rose without thorns, virgin, morning star, outshining heaven; there is no taint of sing in you, but all the gifts of grace, as you bore God while remaining inviolate. She it is who crushed the serpent, dispelling the sins of Eve.

The depiction of Mary as the rose without thorns was so popular that roses were associated with her in medieval manuscript decoration. These carols, set to music in the 20th and 21st centuries, have become firm favourites. They include Benjamin Britten’s Hymn to the Virgin (1934) and Herbert Howell’s A Spotless Rose (1919).

Lady, flow’r of everything,

Rosa sine spina,

Thou bare Jesu, heaven’s king,

Gratia divina.

Of all thou bear’st the prize,

Lady, queen of paradise;

Electa,

Maid mild, mother es

Effecta.Final verse of Hymn to the Virgin, written by an unknown author in the early 14th century.

Listen to Benjamin Britten’s setting on Spotify

Mary also appears in carols as a singer of lullabies. Modern versions of these carols – like Away in a manger and Silent Night – invite us to imagine ourselves at the crib, worshipping the Christ Child and singing him to sleep. But earlier versions give Mary her own voice:

Upon my lap my Soveraigne sits,

And leans upon my brest,

Meanetime His love maynetaines my life,

And gives my sense her rest.Sing lullaby, my little Boye,

Sing lullaby, mine onely joy.When thou by sleep art overcome,

Repose, my Babe, on me,

So may thy mother and thy nurse,

Thy cradle also be.Sixteenth-century carol by Martin Peerson (c.1572-1650).

Listen on Spotify

As we celebrate the Choirbook and its physical survival through the Reformation, we can also trace the survival of its words and images in our carol tradition’s depiction of Mary as the lullaby singer, the rose blooming in the midst of winter.

By Lucy Gwynn, former Deputy Librarian

- The Eton Choirbook has been digitised and can be viewed via the Digital Image Archive of Medieval Music. A log-in is required, but is free to set up.