This exhibition was intended to mark the 200th anniversary of the death of Joseph Banks (1743-1820), an Old Etonian whose influence reached round the world during his lifetime. Another worldwide phenomenon, Covid-19, forced a postponement, not just once, but twice. The exhibition charted Joseph Banks’s global impact through three key themes: Banks at Eton and his early botanising; Banks as plant hunter on James Cook’s voyage round the world in the Endeavour; and Banks the scientific entrepreneur and promoter of economic botany. The outcomes of the voyage and Banks’s subsequent life were immense. The encounters between European explorers and native peoples were sometimes tragic, and the written records often one-sided. In addition, the trade and dominion which developed subsequently provided opportunities for imperial exploitation, the legacies of which continue to this day. After the Endeavour voyage, Banks’s plans to join Cook’s second Pacific expedition came to nothing, and he only made one other significant expedition. Instead, his influence spread worldwide through his other activities: as scientific promoter and correspondent, President of the Royal Society for 42 years, Privy Councillor and adviser to King George III, and de facto director of the Royal Gardens at Kew. Banks published very little himself, but his activities had a profound impact on the world we live in today. Twenty-five years after Eton’s 1997 exhibition Joseph Banks and Friends: Plant Hunting at Eton and Beyond, this is a timely opportunity to reassess his contribution in light of changing attitudes.

William Dickinson after Joshua Reynolds, Joseph Banks, Esq., mezzotint, 1774

[FDA-E.245-2010]

The son of a wealthy landowner, Joseph Banks spent his early years at home on the Lincolnshire fens where he developed a passion for the outdoors. At the age of 9 he was sent to Harrow, where he ‘cared mighty little for his book’, and four years later to Eton. Here his tutor Edward Young noted his ‘great deficiency’ in Greek and Latin, ‘great inattention’, and ‘immoderate love of play’, but found him otherwise ‘a very good-temper’d and well-disposed boy’. He would become one of the most eminent figures in Georgian England, holding the position of President of the Royal Society for over four decades, as well as being a Privy Councillor, and unofficial director of the Royal Botanic Gardens at Kew.

Banks’s reputation as an intrepid botanist is implied by the globe at his elbow and the inscription on the letter under his left hand, a passage from Horace reading ‘Cras Ingens iteramibus aequor’ (Tomorrow we will sail the vast deep again).

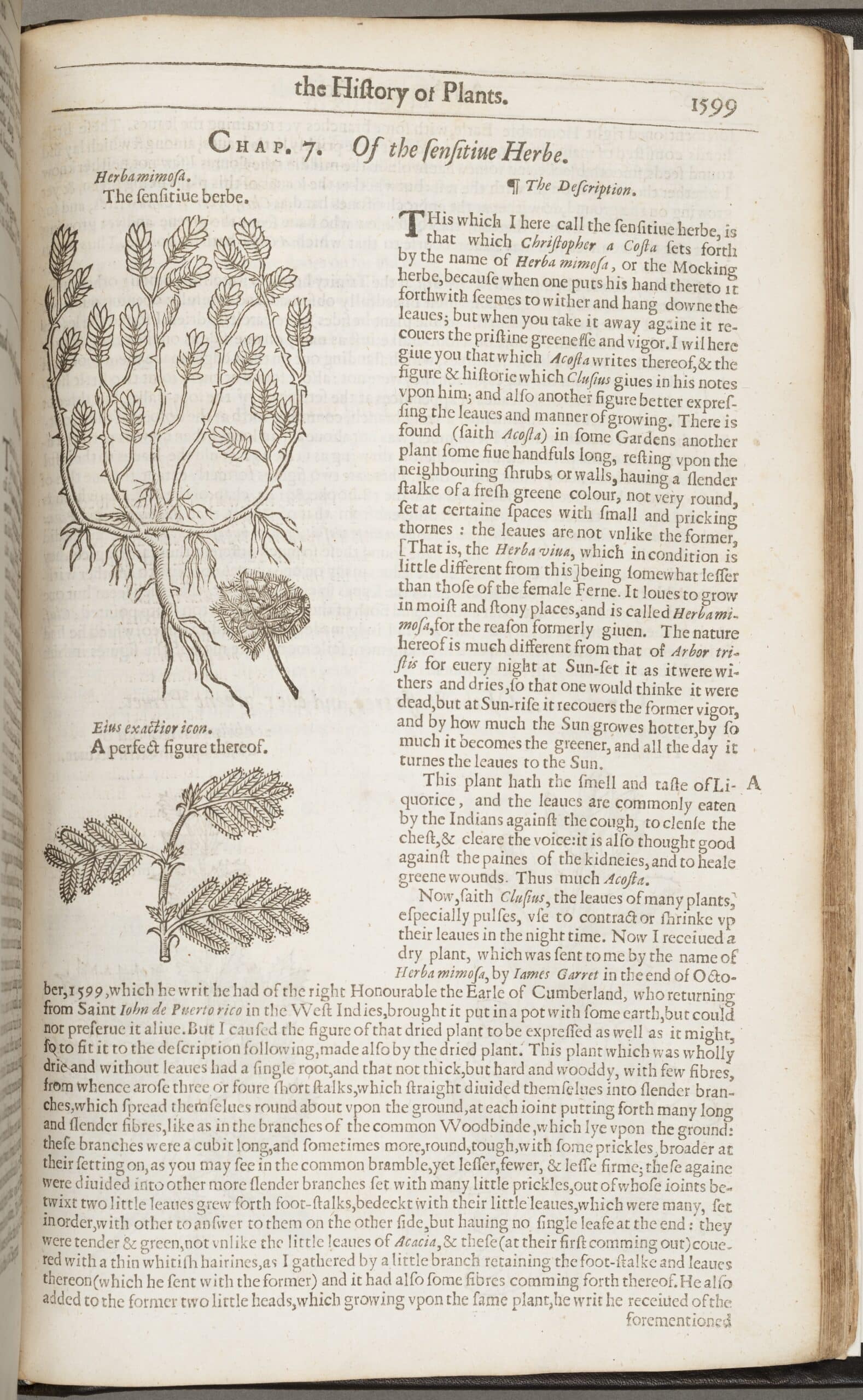

John Gerard, The herball, or Generall historie of plantes, London, 1636

[ECL, Gh. 1.06]

While at Eton, Banks began to teach himself botany, paying the women who gathered medicinal plants for apothecaries’ shops for useful information. Back at home in Lincolnshire, he found an old copy of Gerard’s Herball, illustrated with woodcuts of plants he recognised, and carried it back to school in triumph. In his 1822 lecture to the Royal College of Surgeons of England, surgeon Sir Everard Home retold Banks’s own description of his sudden discovery of his passion for botany as a boy at Eton. Home supposed that it was ‘probably this very book that he [Banks] was poring over when detected by his tutor, for the first time, in the act of reading’.

The botanical renaissance in Europe owed much to a series of books by herbalists, of whom John Gerard (1545–1607) was the best known in England. Gerard’s original edition in 1597 contained numerous scientific errors, and it was completely revised after his death by the apothecary Thomas Johnson, who added hundreds of new illustrations and descriptions to the second edition, published in 1633.

Model of H.M. Bark Endeavour, 20th century

[NHM.32-2015]

In 1766, Banks set his sights on a voyage of discovery, embarking on a survey of Newfoundland and Labrador as an unofficial ship’s botanist. In 1768 he persuaded the Admiralty to let him join James Cook’s expedition to the South Pacific at his own expense with a team of eight collectors, artists and servants, including the Swedish naturalist Daniel Solander, a pupil of Carl Linnaeus. On the Endeavour, Banks and his colleagues collected over 30,000 specimens of plants and animals, including around 1,400 species previously unknown in Europe.

On their return to London in 1771, Cook and Banks became instant celebrities. Cook’s careful charting of the New Zealand coast and the eastern seaboard of Australia were to be of great importance to Britain, and the scientific observations and collections of Banks and his team would eventually challenge the Eurocentric view of nature and mankind’s place in it. Accounts of the expedition’s reception in Tahiti captured the public imagination, creating a popular image of the South Sea islands that endures to this day.

The 366-ton Endeavour Bark was originally the Whitby-built collier Earl of Pembroke, bought into the Royal Navy in 1768 and fitted out for Cook’s first voyage of circumnavigation. Endeavour was 106 feet long and had a draught of 14 feet fully laden; she carried 72 crew and 13 marines as well as Banks’s party. This 1:60 model was built for the Eton Natural History Museum by Mr Norman Paulding in 2005 and took over 420 hours to construct.

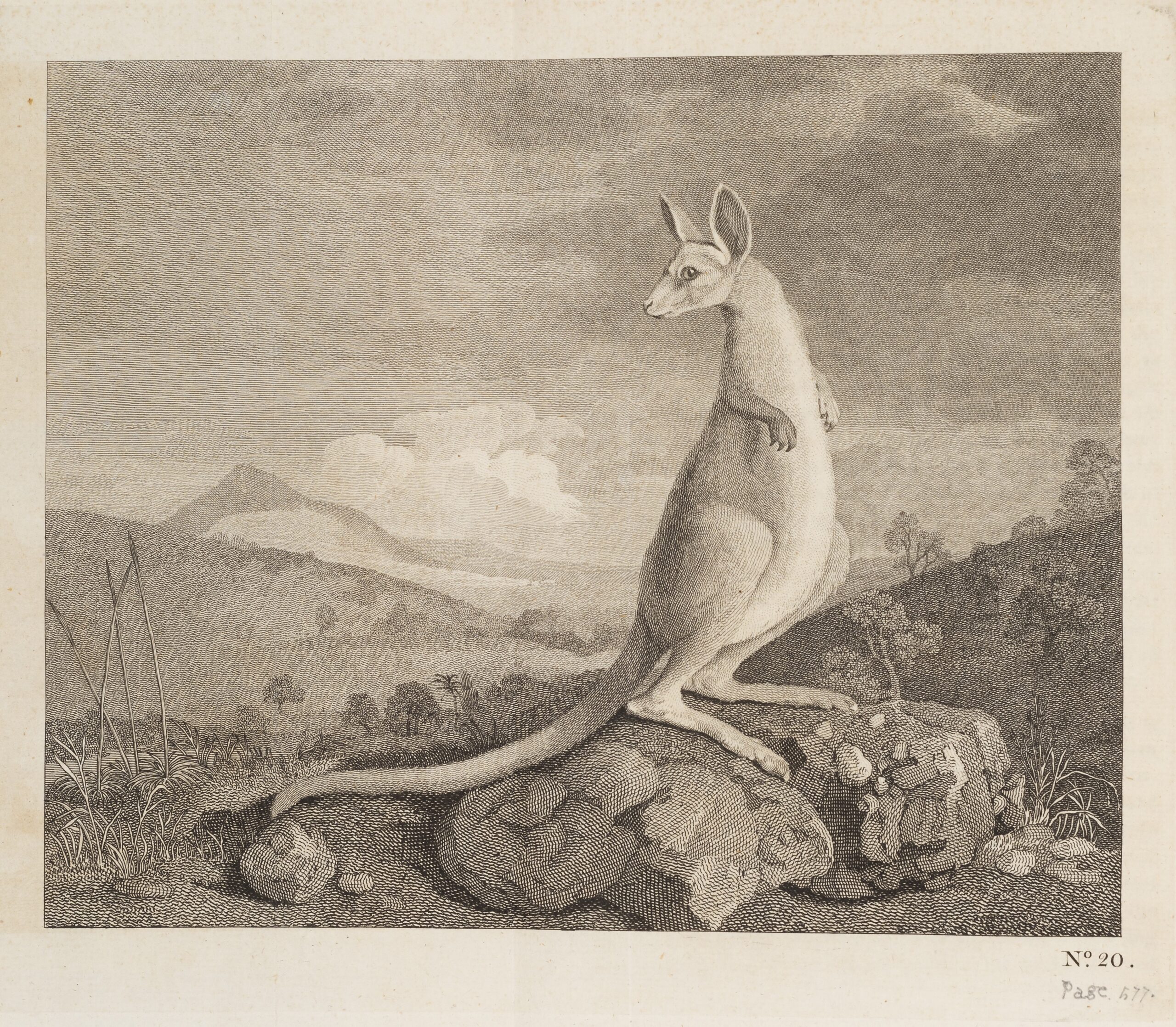

Engraving of the ‘Kanguroo’ in John Hawkesworth, An account of the voyages undertaken …, London, 1773, vol 3

[ECL, Ag.5.05]

After the Endeavour’s return, John Hawkesworth was commissioned to publish Cook’s journals with those of three other expeditions of the 1760s. The official account of the Endeavour voyage includes Cook’s account of his first sighting of a kangaroo on 24 June 1770 following earlier reports from the landing parties:

Excerpts from the Endeavour journal of Joseph Banks

25 [June]. In gathering plants today I myself had the good fortune to see the beast so much talkd of, tho but imperfectly; he was not only like a grey hound in size and running but had a long tail, as long as any grey hounds; what to liken him to I could not tell, nothing certainly that I have seen at all resembles him.

7 [July]. We walkd many miles over the flats and saw 4 of the animals, 2 of which my greyhound fairly chas’d, but they beat him owing to the length and thickness of the grass which prevented him from running while they at every bound leapd over the tops of it. We observed much to our surprize that instead of Going upon all fours this animal went only upon two legs, making vast bounds just as the Jerbua (Mus Jaculus) does. …

Banks’ Florilegium, plate 608 ‘Luffa cylindrica’, Alecto Historical Editions, 1990

[FDA-E.2916:29/5-2016]

One of Joseph Banks’s most substantial scientific achievements was only completed long after his death. Working from original drawings of the botanical specimens collected during the Endeavour voyage, Banks had planned a 14-volume illustrated botanical work to present his discoveries. Between 1773 and 1784, Banks and the naturalist Daniel Solander oversaw five artists and 18 engravers preparing engraved copper plates based on Sydney Parkinson’s drawings and sketches of 753 selected species of plants from the voyage, to be accompanied by scientific descriptions by Solander. After Banks’s death in 1820, there were several proposals or attempts to publish at least part of his Florilegium. Finally, between 1980 and

1990 Alecto Historical Editions under the direction of Joe Studholme, another Old Etonian, completed the monumental task of printing 100 sets of the 738 surviving copper plates, using historical printing techniques touched up with hand colouring.

This one shows Luffa cylindrica, better known as the bathroom loofah.

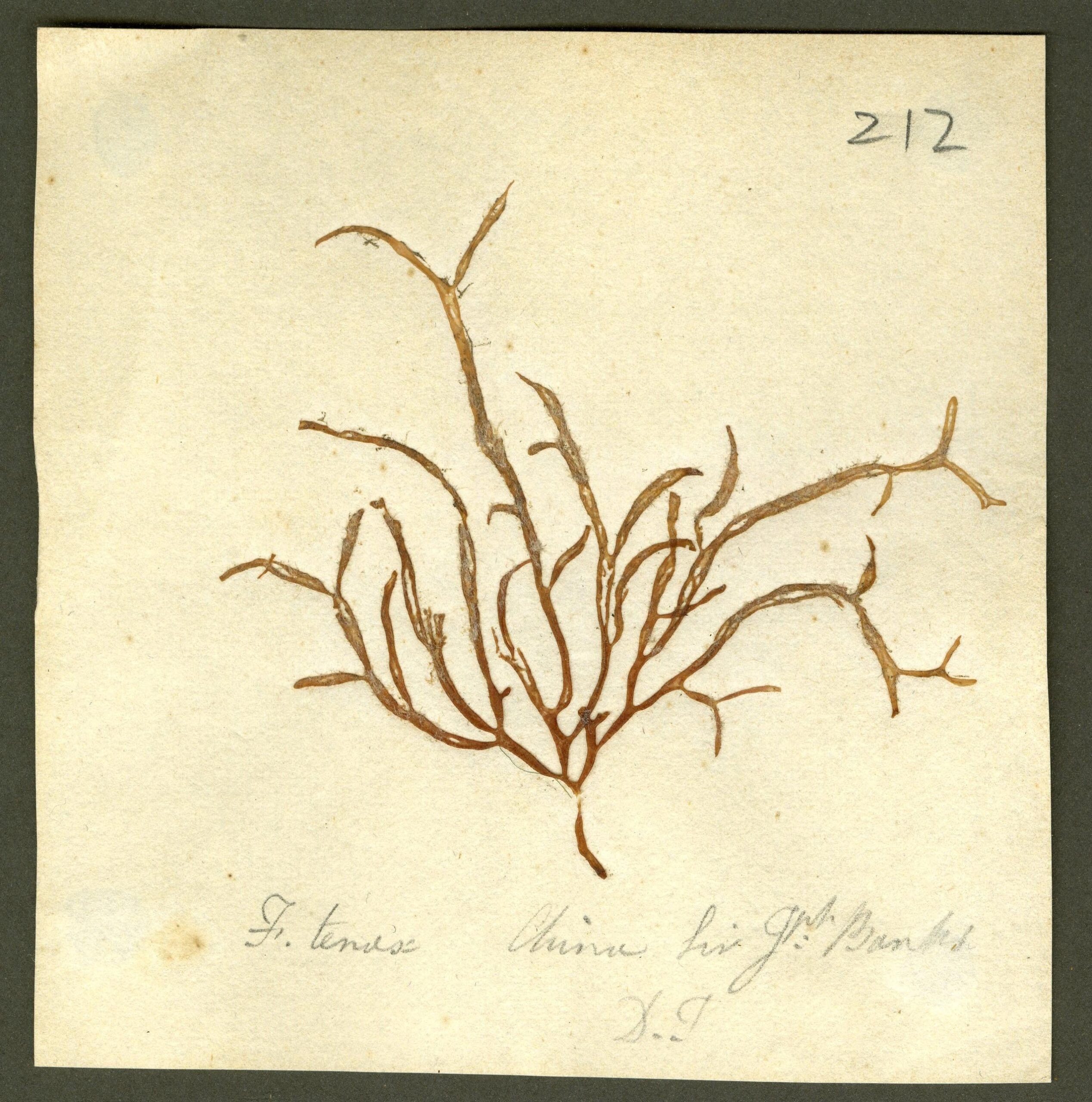

Type Specimen: Red alga (Rhodophyta), Fucus tenax, now Gloiopeltis tenax

[NHM-HH:1.213-2010]

The small piece of red seaweed sent by Sir Joseph Banks to the botanist Dawson Turner (notice the initials DT) was described as a new species, Fucus tenax. This specimen and others in the collections of the Natural History Museum, London and the Eton College Natural History Museum are considered to be the material upon which the original species descriptions and illustrations published by Turner (1806, 1808-1809) were based, making them type specimens of the species now known as Gloiopeltis tenax.

This seaweed was extensively used in Japan, China and Korea as a source of glue and gum and has been more recently extensively employed in a wide range of specialised applications including the conservation of antiquarian objects. With his eye for economic botany, Banks raised with Turner the possibility that similar species in Britain could be used for the extraction of ‘gelatine’.

The catalogue for the exhibition held at Eton in 2022 may be viewed or downloaded below.

With grateful thanks to Joe Studholme for permission to reproduce catalogue images from Banks’ Florilegium, Alecto Historical Editions, 1990.